Forget Software Vulnerabilities, Hardware Security Must Improve Before It's Too Late

The industry needs to step up to prevent more security vulnerabilities

In December, USA retailer Target discovered that it had been the victim of a major security breach affecting its Point of Sale (POS) terminals, leading to the theft of payment data from about 40 million credit and debit cards.

The theft was caused by malware that was introduced to the POS systems through a hardware encryption vulnerability that could have been prevented.

In another case last August, famous hackers Charlie Miller and Chris Valasek succeeded in hacking into a Toyota Prius and a Ford Escape to show just how easy to take control of the control system of a modern car.

These are just two examples of a growing trend where the more connected devices around us become, the more susceptible to cyber attack we are.

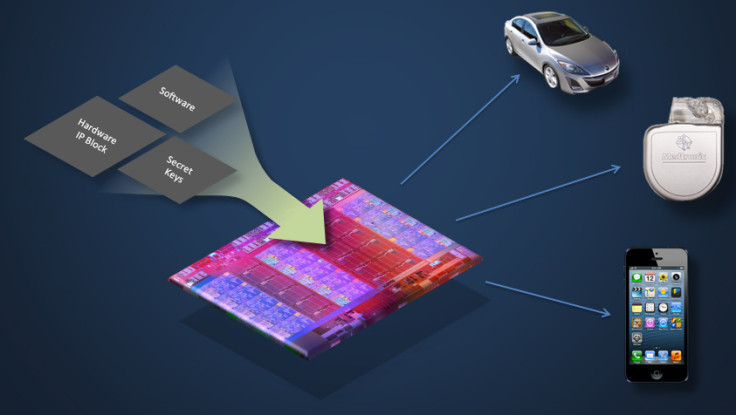

While it may not be a big deal if a cybercriminal hacks your smart fridge to send spam, the potential risks associated with maliciously taking control of a pace maker or a car, are obvious to all.

To combat this problem, computer scientists from the University of California have devised a new way to detect security problems, by testing hardware and how it integrates with software.

Using Gate-level Information Flow Tracking, a team of scientists from UC San Diego and UC Santa Barbara have invented a tool that can tag critical parts of a hardware's security system and then monitor how each part affects the system.

Changing the way we look at security

Currently, the security industry's focus on analysing software for potential security vulnerabilities is based on the assumption that the chip the software runs on is completely secure - when that is not always the case.

Hardware is made up of many interconnected blocks which share resources and perform complex interactions. At times, the way the hardware is designed can enable encrypted memory to be leaked, so it's crucial to look at how software and hardware interact.

"Many types of encryption revolve around a secret key, but that secret key can easily be leaked. Even if you encrypt things, a lot of the time there are malicious backdoors that allow you to figure out the key, which would make all your encryption useless," Ryan Kastner, a professor of computer science at the Jacobs School of Engineering at UC San Diego tells IBTimes UK.

"In some cases, the key will go to an unsecure place, totally unintended by the hardware designer."

Kastner uses the example of a smartphone.

Because a smartphone chip consists of tens of thousands of transistor cores and the interfaces between each core is very complex, it is sometimes possible for a processor running an untrusted app to slip through and access memory in an encrypted section of the phone.

"The hardware is very complex, with millions of transistors operating at the same time, so it's hard for the hardware designer to realise, and the key might be leaking to somewhere no one thought it would," he says.

"Our tool is the first to allow you to understand if the encryption key being leaked through something called a timing channel, whereby you can figure out the key by looking at the amount of time encryption cores take to encrypt data. The tool would tell you if the key is leaking, so you can change your system and test it again to make sure you've eliminated it."

Stepping up security before it's too late

Kastner and his colleagues have formed a company called Tortuga Logic in order to commercialise their tool, and are currently working with two well-known semiconductor companies, and in talks to work with a third.

He warns that improving security is not just an issue for the computer industry – it affects any company seeking to design any kind of digital system, from a smartphone to a smart home appliance, car or medical system.

"This is of critical importance to any hardware designers making any future systems, especially systems that affect our lives. These systems are extremely complex. There's no one who understands everything about a computer system," Kastner stresses.

In 1994, the floating point bug produced an error in Intel Pentium P5 processors, so that computers sometimes produced incorrect results for calculations used in maths and science. Eventually, the computer industry had to change the way it built certain components of computer chips.

Kastner says that in many companies, the hardware and security departments do not work together, and so we are heading towards a similar situation.

"There's a lot of classified chatter about what cyber attacks the US military is worried about. It's all brewing," he says.

"There's starting to be a significant awareness raised at hardware companies like Intel, Qualcomm, Samsung, anyone designing devices we use, and they're are realising that if they don't take into account the security of the hardware, that potentially a huge issue could happen."

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.