Functioning human muscle grown from skin cells for the first time

The new research will enable researchers to better understand rare muscle diseases.

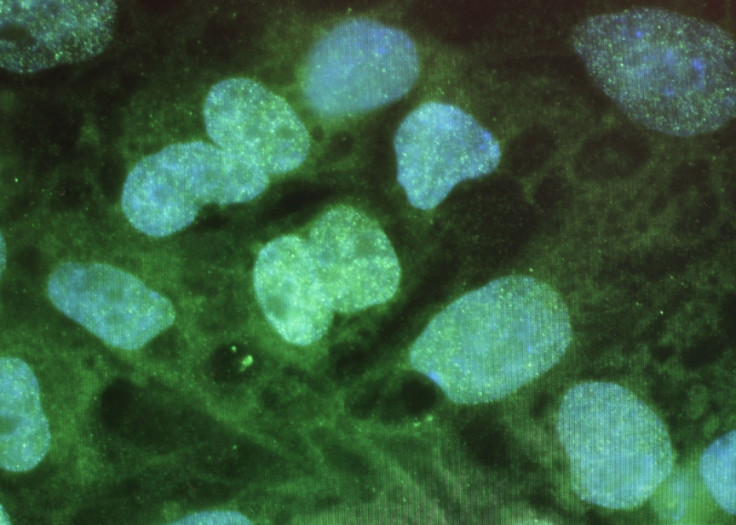

In a world first, biomedical engineers have grown functioning human muscle tissue from stem cells – the body's internal repair system.

Researchers hope that being able to generate muscle from non-muscle tissue will the lead to new cellular therapies and treatments for rare diseases.

"Starting with pluripotent stem cells that are not muscle cells, but can become all existing cells in our body, allows us to grow an unlimited number of myogenic progenitor cells," said Nenad Bursac from Duke University.

"These progenitor cells resemble adult muscle stem cells called 'satellite cells' that can theoretically grow an entire muscle starting from a single cell."

Previously, Bursac and his colleagues were able to grow muscle fibres using small human cell samples taken directly from muscle tissue. But in the new study, they used so-called pluripotent stem cells, which can be taken from non-muscle tissue, such as the skin or blood, and are able to produce any cell or tissue in the body.

The researchers took these stem cells and engineered them so they grew into muscle stem cells, which they in turn used to create the functioning muscle tissue.

"It's taken years of trial and error, making educated guesses and taking baby steps to finally produce functioning human muscle from pluripotent stem cells," said Lingjun Rao, first author of the study. "What made the difference are our unique cell culture conditions and 3-D matrix, which allowed cells to grow and develop much faster and longer than the 2-D culture approaches that are more typically used."

The resulting muscle fibres can contract and react to stimuli much like the tissue inside our bodies, and have been shown to function when implanted into adult mice. However, the muscle is not as robust as native muscle tissue.

Despite this, the techniques developed by the team hold potential for helping researchers understand rare muscle diseases and developing new, personalised, regenerative therapies.

"The prospect of studying rare diseases is especially exciting for us," said Bursac. "When a child's muscles are already withering away from something like Duchenne muscular dystrophy, it would not be ethical to take muscle samples from them and do further damage. But with this technique, we can just take a small sample of non-muscle tissue, like skin or blood, revert the obtained cells to a pluripotent state, and eventually grow an endless amount of functioning muscle fibres to test."

For example, in patients with genetic muscle diseases, researchers may be able to take stem cells, fix the genetic malfunction, and then grow new patches of healthy, functioning muscle.

The research is published in the journal Nature Communications.