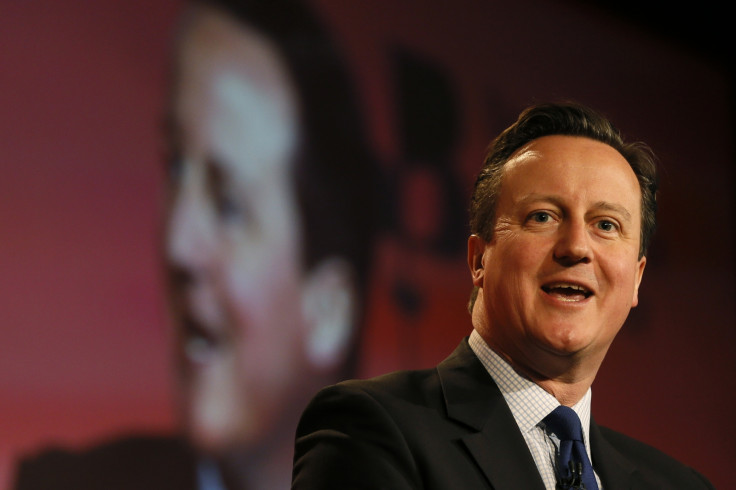

General election 2015: David Cameron has shown his hand and he is a quitter not a fighter

Before he has even won a second term as prime minister, David Cameron has ruled out standing for a third. Presumptuous? Arrogant? Stupid? Probably, possibly. Who knows?

But one thing exposed by this slip – which has irritated those in his team trying hard to win the election just a handful of weeks away – is Cameron's essential weakness: he's a quitter, not a fighter.

I think people will be asking themselves why on earth, what was all the fuss about? Why on earth didn't we have these things before?

Cameron does not exude the character of a man of substance, who believes what he says and says what he believes. Cameron is a malleable creature, which is handy for U-turning. He bends and winds and slithers through politics, changing direction – often to retreat – when barriers appear ahead.

Take the recent ruckus over the television debates. Cameron was once a TV debate evangelist. From his past comments, you might think he firmly believes in the principle that political leaders should debate in front of the nation on TV during an election period.

"You know we've been going on for years about let's have these debates and I think it really vindicated having that," Cameron told the BBC in April 2010. "I think people will be asking themselves why on earth, what was all the fuss about? Why on earth didn't we have these things before?

"We should have done and it's great they're under way now and I think we'll have them in every election in the future and I think that's a really good thing for our democracy."

To be fair to Cameron, he is taking part in TV debates ahead of the 2015 general election. But he has kicked up an almighty stink throughout the negotiating process with broadcasters, at one point throwing a paddy and offering an "ultimatum" to try and force through what he wanted.

Battleground is wide and varied

This election is the most multi-party in modern British history and new territory for the country's politics. The polls are narrower than they have ever been and there are several serious contenders across the country. So the broadcasters are keen to encompass as many party leaders as possible – and proposed a couple of seven-way debates.

But Cameron wriggled and writhed and tried to get out of this because it is not in his political interest to take part. He does not want to share a platform with the populist centre-right Ukip leader Nigel Farage, who Cameron is already haemorrhaging traditional Tory support to.

And Cameron wants his main rival, Labour leader Ed Miliband, left alone to joust with the liberal-left parties in the hope that it will split Miliband's vote even further and damage his chances of triumph in May. On top of this, Cameron is bluntly refusing to do a head-to-head debate with Miliband, to cries of "chicken" from the opposition benches.

In the end, Cameron's tantrum more or less paid off. He will not have to debate Miliband in a head-to-head, instead taking part in Q&A sessions alongside the Labour leader, and he only has to do one seven-way debate where he will have to confront Farage.

This is the essence of Cameron: too weak to take on difficult debates, too duplicitous to stick to the principles he claims to have.

His weakness has shown up before. He delayed and dithered over intervention in Syria – a policy he agreed with – and was too weak to win the debate and enough support to get military action through parliament, which rejected it.

Cameron is reluctant to sack ministers he wants to get rid of because he does not have the stomach, or the support on his backbenches, to start picking fights with those who are supposed to be under his authority. He is notoriously loyal to his ministers during times of political and personal crises.

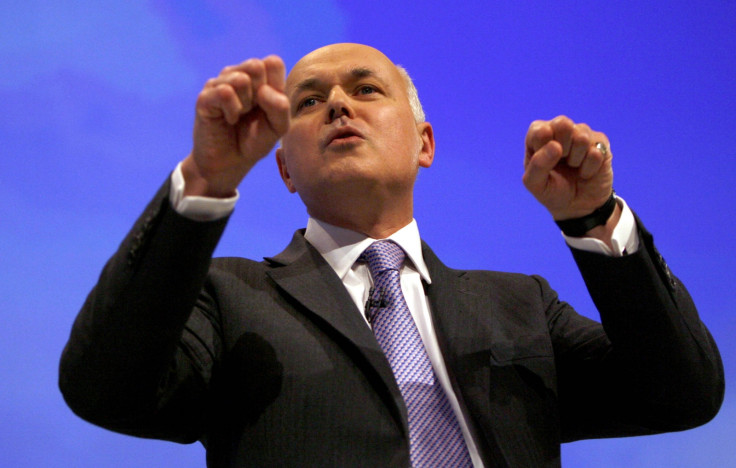

Cameron bottled the Iain Duncan Smith issue

In a cabinet reshuffle in 2012, he bottled shifting the unpopular work and pensions secretary, Iain Duncan Smith, to another ministerial role.

"If there was a failure of nerve, it concerned the department for work and pensions," wrote Janan Ganesh of the Financial Times.

"At the heart of government, Iain Duncan Smith is rated more as a visionary than as an executive. There are worries that welfare reform, always a confounding business, is a comedy of errors waiting to commence. The Treasury would also like deeper cuts to welfare than Mr Duncan Smith might contemplate.

"Mr Cameron is reported to have asked the work and pensions secretary to accept another job (perhaps justice) but was rebuffed."

But perhaps one of the most defining examples of Cameron's inherent weakness, his tendency for quitting before the debates get difficult, is over Europe.

Scared of a backbench rebellion within his party, where there is widespread euroscepticism, Cameron sought to buy the silence of those questioning his leadership with a pledge to hold a referendum on the UK's membership of the European Union.

This is despite the fact that he is in favour of the EU and wants the UK to remain inside. Rather than taking the argument to his backbenches and asserting the party's pro-EU policy, Cameron bottled it because he does not have the desire to fight.

It was easier just to tangle himself up in an awkward compromise and worry about it later. Who knows, maybe he would even lose the election anyway and not have to worry about it at all?

Avoiding tough times ahead

Cameron knows if he wins a second term, he is in for a very difficult time in office. He is very unlikely to be elected with a majority, meaning he will have failed to secure control of the House of Commons in elections against two of the most unpopular Labour leaders ever.

Once again he will be forced into a coalition of convenience. Will his backbenchers tolerate another five years of compromise with the Lib Dems? Would the staunchly pro-EU Lib Dems even enter another coalition with the Conservatives if it means supporting an EU referendum?

Knowing he will stand down at the end of the parliament anyway, will the MPs and ministers on Cameron's benches want to wait around for a new leader and let the speculation, infighting and Machiavellianism damage the party throughout the whole term? Or will they move sooner to oust Cameron and get it all out of the way early?

Given Cameron's history of choosing the easiest path forward, if the going gets tough then he will probably just get going on his merry way anyway.

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.