Hacksaw Ridge: How recreating the bloodiest battle of WWII gave Mel Gibson his comeback

Production Designer Barry Robison spoke to IBTimes on the challenge of recreating Gates of Hell battlefield

Faith and redemption have defined the last decade of Mel Gibson's years in the Hollywood wilderness. Little surprise, then, that the troubled star's Oscar-nominated comeback effort, the Second World War epic Hacksaw Ridge, asks deep questions about inner conviction.

Gibson's first directorial feature since 2006's Apocalypto tells the story of conscientious objector Desmond Doss (Andrew Garfield), a devout Seventh Day Adventist, who, despite refusing to carry a rifle due to his pacifist beliefs, was granted his wish to serve in battle as a medic.

As fate would have it, Doss and his fellow soldiers in the 77th Infantry Division were sent to the Battle of Okinawa, the most unique and bloody conflict of the Pacific War.

This seemed a sure-fire death sentence for a soldier with Doss' convictions, who, when asked in mocking terms by fellow soldiers what he would do if faced with an armed Japanese soldier, replied: "Well, I guess he'd kill me, but I might try to take the gun away from him if I could."

Doss achieved the impossible. As others ran in fear, he scaled the 400ft Maeda Escarpment in supreme faith, single-handedly saving 100 men, including Japanese soldiers, all without firing a single bullet. He became the first conscientious objector to receive the Medal of Honour for actions above and beyond the call of duty during World War Two.

For Gibson, the concept of faith triumphing over adversity and dark times holds great personal resonance.

The Lethal Weapon star, now 60, has endured his own tumultuous demons. Blacklisted by Hollywood after a much-publicised drink-driving charge and anti-Semitic tirade towards the arresting officer in 2006, he then pleaded no contest to a misdemeanour battery claim brought by former girlfriend Oksana Grigorieva in 2010.

A leaked audiotape full of drunken threats to kill and slurred racist abuse followed, leaving the former heartthrob with little place to hide. It also sharply undermined the devout Christian beliefs that saw Gibson direct 2004's bloodthirsty Passion of the Christ – which, it may surprise you to learn, is now the most successful independent film of all time.

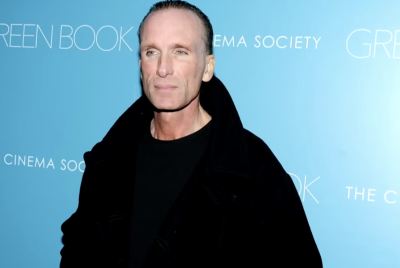

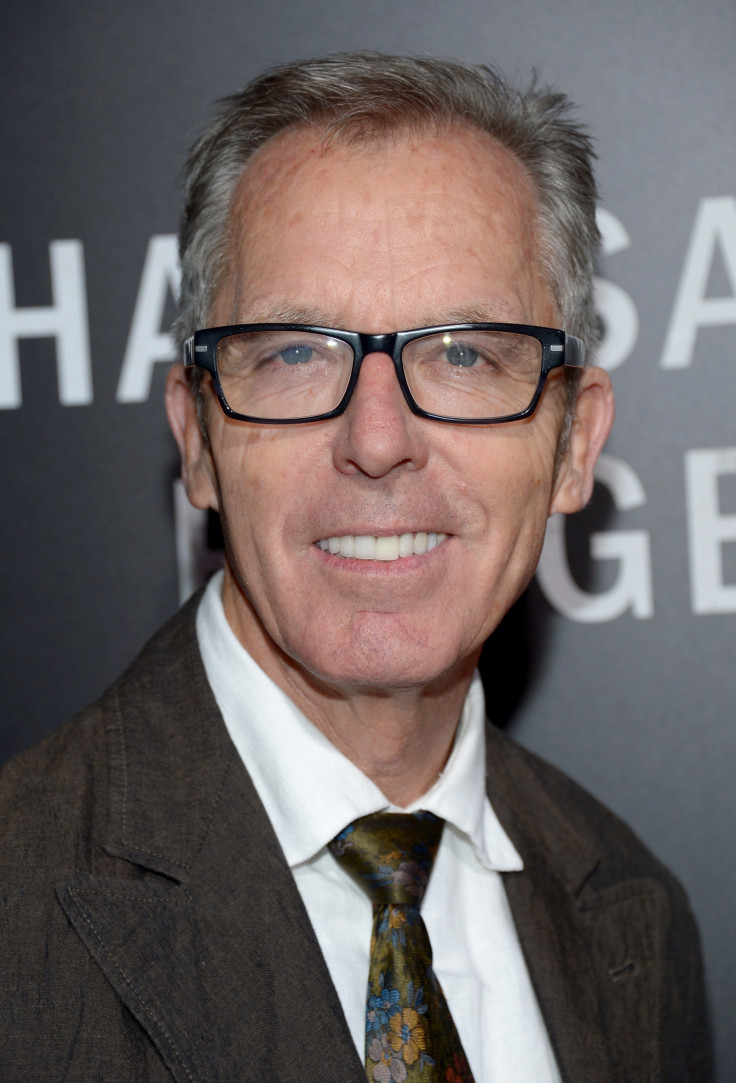

The responsibility for bringing Hacksaw Ridge to life fell on production designer Barry Robison, a veteran of his trade, from small features such as October Sky to full-blown blockbusters including X Men and The Chronicles of Narnia. Robison admits feeling "worried when I took the call, because, let's not sugarcoat it, Mel has been in the penalty box. He came straight out and said 'I screwed up, I fucked up. I've been out of it for a while' – and what do you say to that?

"I responded to that. I saw in the beginning that he'd been out of the director's chair for 10 years and was finding his way – a man reading a road map."

Robison says he was drawn to Gibson's strong, simple, vision: "Give me the ugly intensity of war".

To fully immerse and disorientate the audience, Gibson made clear that an emotional charge had to be run through the battle scenes.It helped that Robison, as a student of psychology, could appreciate this dual aim.

Finding the right location in which to express this was essential. The film, far from being shot in Japan, was largely produced in Sydney and the suburbs of Australia. Early opening scenes introducing Doss' home life in Virginia and Dorothy Schutte (played by Teresa Palmer), the nurse who would capture his heart in marriage until her death aged 71 in 1991, enjoyed a more neutral colour palate, while the bootcamp and battlefield sequences, endured harsher tones.

But Robison's real influence, and the true magic of the film lies in the battlefield re-created from scratch at a pasture in Bringelly, a small, rural western suburb of New South Wales. Gibson "fell in love" with the location because it still maintained the expansive rural feel of a 20th-century town.

This authentic, natural environment helped cultivate the emotional ties Gibson had drawn from legendary Japanese director Akira Kurosawa, specifically his 1985 film Ran – even extending to the cinematography itself. As Robison explains, "Mel wanted things a little more old school, he didn't want us to use any of the more modern tools available to us today, like Sketch Up or any kind of 3D rendering,"

However, there were limits, as the team were working under a "very, very tight" budget. "Greenscreens are expensive" says Robison. "My armourer had to count the number of bullets being used per shot, it was a very, very tight budget. I like to say that for me I had three jeeps and one truck – I've heard that we had $40m [£31m], but the reality was around $15-$20m."

Undeterred, Gibson used these to enthuse a 'backs against the wall' philosophy, and push for excellence.

In a bid to ensure historical accuracy, Robison also made a trip to the National World War II Museum in New Orleans. But despite mass-documentation on the battle, the only visual cues were aerial images taken from the sky, showing 'moon crater'-like land. This meant first-hand accounts, in all their bloody horror, became indispensable.

Indeed, for all that has been made of the gore factor in the film, enhanced by Gibson's reliance on make-up rather than pixels, none of it amounts to fetishisation. The reality of war is captured in brutally truthful terms – guts did spill and limbs were blown off in a barrage of screams, colour and a head-spinning sense of threat. As Joe Clapper, a 95-year-old Okinawa veteran told People after seeing the film: "But when you've been there, that's what it's like."

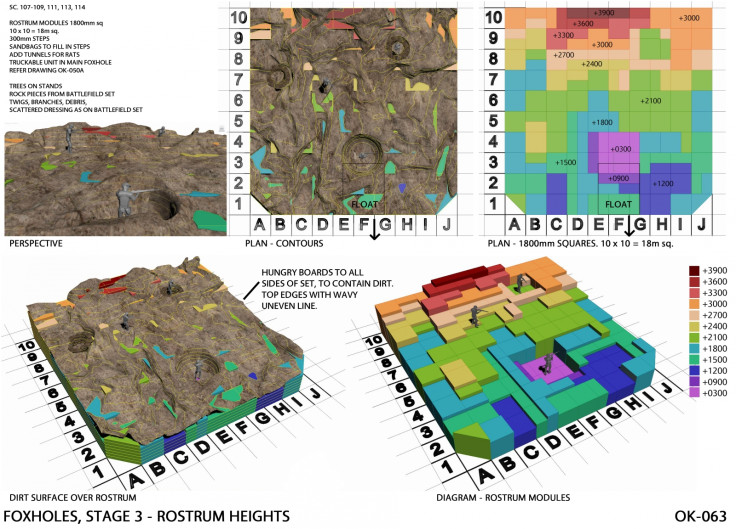

The battlefield itself was dug in a bowl shape extending five to six acres in order to disguise the surrounding eucalyptus trees, made invisible on screen film due to the large amounts of smoke deployed.

Two particular techniques were brought in to give Gibson as much control as possible over the environment. First, greensmen were on standby whenever Mel was on set, so that if the shot wasn't dynamic enough "he could convey that to the greensmen and within minutes they could resculpt the landscape," giving an unprecedented level of real-world creative freedom.

Second, Robison worked with art director Geoff Kemmis to construct a two-metre by three-metre scale model of the battlefield, which Gibson found "great fun, because he could use it to help visualise with the stunt coordinators and visual-effects team."

But even more ambitious still was the creation of the Hacksaw Ridge escarpment itself, a key to setting the hellish scene of battle and conveying the scale of Doss' rescue achievements.

Robison remembers: "I found the ideal cliff in Goulburn. It had been a rock face that had been carved out in the later part of the 19th century by the railroad, so it looked weather-beaten and war-torn, and that became the big escarpment that you see in the movie."

The battlefield was built on the rise so the Japanese were above the Americans, so it needed to be at the bottom of an 18-degree slope. They had to dig down 40 feet by 60 feet across, so it was a huge engineering feat.

"Stunts didn't feel the actual cliff face we were working on was actually safe enough for the actors to be working on. So we had to back up to Goulburn and take a mould of the actual cliff face; we ended up setting up scaffolding and putting these plastic sheets over the scaffolding."

But drawn together despite all the odds, the set design comes into its own in the final half hour of Hacksaw, encompassed by an emotive final battle scene – painterly and operatic. Fire burns high, time slows – all building towards a final scene that sees Doss anointed in almost saintly terms.

It feels like a deliberately personal Gibson ending, overtly religious and layered with his own convictions. His support for Doss, who never gave up on life and instead chose to famously say "please Lord, let me get one more" as he saved men throughout the night – is a statement in support of faith in every sense.

Robison confirms it was Gibson making a "very strong choice" at the conclusion. "I need this moment", he told the crew – discarding the script. The message is clear: from the gates of hell you can find redemption.

"Hacksaw is the story of a man with very strong beliefs, it is a story of redemption for Mel. Need to look at this story as a metaphor. It's Mel as a storyteller, Mel as a man, coming back from the abyss," says Robison.

Both Doss and Gibson shared a similar belief in the power of faith in their own convictions, and come Oscars night on 26 February, only a fool would discount the chance of the outcast clawing his way back to redemption – whether we like it or not.

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.