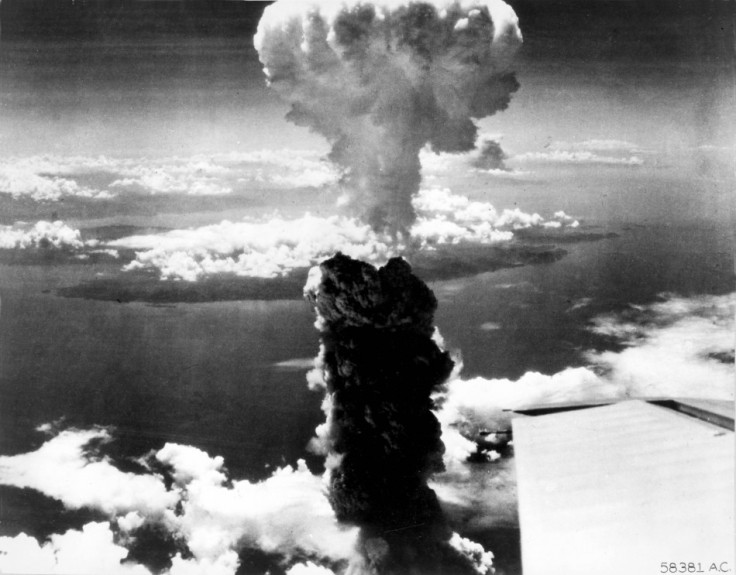

Hiroshima and Nagasaki: Did the US need to drop atomic bombs on Japan?

They were two bombings that unleashed a devastating hellfire of light, heat and radiation, causing death and destruction on an apocalyptic scale unimaginable a few years beforehand.

Now, the names of the Japanese cities Hiroshima and Nagasaki are notorious tombstones in history. The two atomic bombs dropped on the cities in August 1945, 70 years ago, claimed as many as 250,000 lives, according to some estimates of the death toll. Most were civilians, though there were a lot of military casualties too. As well as those killed by the initial blasts, radiation exposure claimed others later on.

Hiroshima and Nagasaki symbolise the logical conclusion of rapid scientific advancement and a never-ending struggle for resources, power and dominance that has marked human society since the dawn of civilisation: a potentially world-ending nuclear war.

Since the bombs were dropped in 1945 − "Little Boy" on Hiroshima on 6 August, and the more powerful "Fat Man" on Nagasaki on 9 August − a debate has raged.

Over the past 70 years, a revisionist movement has grown to challenge the consensus. Was it really necessary to sacrifice a quarter of a million lives, mostly civilians, in the furnace of an atomic bomb? Or was it a callous act of mass murder for reasons other than ending the war?

Perhaps the best summary of our retrospective judgement of Hiroshima and Nagasaki was offered at the time of the 60th anniversary by the military historian Max Hastings.

"Those who today find it easy to condemn the architects of Hiroshima sometimes seem to lack humility in recognising the frailties of the decision-makers, mortal men grappling with dilemmas of a magnitude our own generation has been spared," he wrote in The Guardian.

To mark the 70th anniversary of the only uses of nuclear weapons in warfare to date, IBTimes UK looks at the arguments against the US bombing of Hiroshima and Nagasaki and challenges the revisionist narrative that has emerged.

Japan was ready to surrender before the bombs were dropped.

Revisionists suggest that the Japanese government was already preparing to surrender before Hiroshima. But there is little substantial evidence to support this claim.

Japan's economy, resources and military were mostly spent after years of war. Tokyo had been the target of a fierce and destructive conventional bombing campaign. And the Soviet Union had indicated for months that its non-aggression pact with Japan was now redundant. Revisionists argue that had the Japanese been offered a deal whereby the existing rulers could have held on to power in exchange for peace, they would have surrendered.

But diplomatic messages intercepted by US intelligence, and only released to the public decades later from the 1970s onwards, revealed the overwhelming will of Japan's upper-echelons to carry on fighting to the end.

Japan was forced to surrender because of the atomic bomb raids on Hiroshima and Nagasaki, which cost lives in order to save many more. It was the lesser of two evils because, had the Allies been forced to invade the Japanese mainland, perhaps millions more may have died in the fighting −Japanese, Americans, Chinese, Russian, British and others.

By unleashing the devastation of atomic weapons on Japan, the US had delivered the ultimate show of strength and signalled to the Japanese leadership that if it fought on, it would inevitably lose.

When the bombing of Hiroshima yielded no surrender or even a response from the Japanese rulers, Fat Man was unloaded on Nagasaki three days later, a doubling-down.

"The fundamental political reality is that it was Japanese, not American, leaders who controlled when and how the Pacific war would end," wrote the eminent war historian Richard B Frank in his 1999 book Downfall: The End Of The Imperial Japanese Empire.

"Those insisting that Japan's surrender could have been procured without recourse to atomic bombs cannot point to any credible supporting evidence from the eight men who effectively controlled Japan's destiny: the six members of the Supreme Council for the Direction of the War, Lord Keeper of the Privy Seal Kido and the Emperor."

Frank adds that "no relevant document has been recovered from the wartime period", nor did any of the Japanese leaders in their war-crimes trials, under the cosh of the death penalty, testify that they would have surrendered earlier. Moreover, the Emperor Hirohito's diary gives no indication of how the Allies could have induced an earlier surrender.

It wasn't the atomic bombs which caused Japan to surrender. It was the Soviet Union.

Revisionists argue that it was the ending of the non-aggression pact between the Soviet Union and Japan that was the real trigger for a Japanese surrender and it was enough without the dropping of atomic bombs to bring it about. But this ignores the chain of events as they happened.

In 1941, Japan and the Soviet Union signed a non-aggression pact similar to the 1939 Ribbentrop-Molotov pact between Nazi Germany and the Kremlin. This gave Japan the confidence that it would not be attacked from the east by the Soviets and allowed it to focus on its Pacific War with the US.

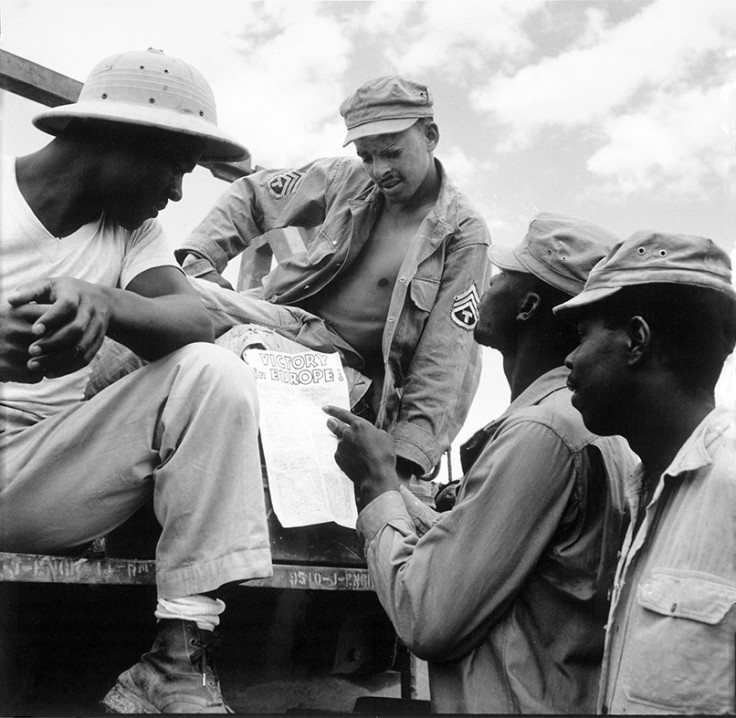

But in February 1945 at the Yalta conference between the leaders of Britain, America and the Soviet Union, Franklin D Roosevelt convinced Joseph Stalin to abandon his non-aggression pact with Japan within three months of the defeat of Germany and declare war on Tokyo.

In April, the Soviets denounced its pact with Japan. A statement read by the Soviet foreign minister to the Japanese ambassador declared that the pact "has lost its sense, and the prolongation of that pact has become impossible" because Germany was at war with the Soviet Union, and Japan was an ally of Germany.

The Potsdam Declaration in June, after the war in Europe had ended with the fall of Berlin, issued the demand from the Allies to Japan that it surrender unconditionally.

"If they do not now accept our terms, they may expect a rain of ruin from the air, the like of which has never been seen on this earth," said the newly elected US president, Harry S Truman, in an ominous warning of what was soon to come.

Japan met the declaration with silence and the war in the Pacific continued. On 6 August Little Boy was dropped on Hiroshima. On 8 August the Soviet Union declared war on Japan. And the following day, Fat Man was dropped on Nagasaki.

Tsuyoshi Hasegawa, the University of California historian, advocates a position between revisionism and the traditional consensus. While Hiroshima sharpened the minds of the Japanese leadership, it was the Soviet declaration of war that was checkmate, posits Hasegawa. Japan was relying on peace with the Soviet Union for it to carry on fighting the US because it was already hobbled by years of fighting. It couldn't fight a war on two fronts.

Moreover, the atomic bomb was just a new way of doing what was already well-established in the war: the intense bombing of densely populated urban areas. Tokyo had already been devastated by a firestorm of Allied bombings. So why would an atomic weapon make any substantive difference to the mindset of the Japanese leadership?

Instead they were holding out for a negotiated settlement, brokered by the Soviet Union, which would allow those in charge to retain power and avoid war crimes trials in exchange for ending the conflict. The Soviets crushed this Japanese strategy and, Hasegawa argues, did more to end the war than the atomic bombings.

But Robert Maddox, a historian and editor of Hiroshima in History: The Myths of Revisionism, told History News Network that while the cancellation of the Soviet-Japan non-aggression pact was an important setback for Tokyo, "it did not come as a shock as did the bombs because the Japanese had been observing the Soviet build-up in the Far East for months".

They could have demonstrated the atomic bomb's power on a deserted area of Japan rather than killing hundreds of thousands of people.

President Truman and his generals didn't know if the bombs would work, so the Manhattan Project was always acknowledged as a big gamble.

To have dropped them in an uninhabited area after notifying the Japanese to pay attention, and then failing to deliver on a promise to demonstrate the awesome power of an atomic weapon, would have been a serious strategic blow to ending the war by inducing surrender.

Also, without using the atomic bomb as other bombs had been − on major urban areas with important military and industrial targets − the true impact of the weapon could not have been fully comprehended by the Japanese. This had to be a big enough blow to force a surrender.

We also run the risk of projecting our own standards and context onto those of the past. In 1945, civilian casualties had been accepted as a necessary price of a war to defeat the fascist threat. All civilian populations, except the Americans, had been hit. Atomic bombs were a more efficient way of doing the same thing: destroying infrastructure and killing people. It's horrible, but it's the reality of war.

The scale was different, but the principle was the same. There is little moral difference between dropping a single atomic bomb and sending an entire air fleet to devastate a city with conventional weapons.

Truman just wanted to intimidate Stalin.

There is a revisionist argument that the real purpose of the bombings was not to induce a Japanese surrender, which was already imminent, but as a show of strength to intimidate the Soviet Union at the dawn of the Cold War.

Moreover, the Manhattan Project to develop the atomic bomb was vastly expensive − a cost that the US administration had to justify − and could only do so by using the devices.

"Although Stalin did not appear to be impressed by the news [of the US development of a powerful new weapon], Truman hoped the information would increase the pressure on Stalin to concede to the Allies' demands regarding the post-war division of Europe," according to The History Channel's website.

It may be true that a consequence of the bombings would be to shock the Soviet Union (though Truman had fought hard to win Stalin over in the campaign against Japan). Even if it were true, it was secondary to the ultimate goal: a Japanese surrender. As has been demonstrated above, this was clearly the priority of the US because it meant not having to invade mainland Japan and spend even more lives to end the war.

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.