Violence in Videogames is Boring Say Hotline Miami Creators

Since you started playing videogames, how many people have you killed? 10,000? 100,000? More? Those of us who have been into games since we were kids will have by now racked up body counts well into the hundreds of thousands. Some of us might have even tipped a million.

But it's not like we care. Month on month, year on year, the AAA factory finds new ways to desensitise us. In its constant bid to keep killing fun, the mainstream game industry has steadily changed, going from pixelated hits like Space Invaders, to gory schlock like DOOM, onto urbane war games like Call of Duty. But regardless of the aesthetic, large-budget shooters generally have one thing in common: They don't give a damn about the people that die.

With the exception of maybe Spec Ops: The Line, which in 2012 questioned everything about war shooters (more on that later) AAA games all suffer from lack of a conscience. CoD and Halo try to justify themselves with the occasional mawkish cutscene, but for the most part, those games are about having fun with guns. You might argue they should be. It might be ugly and tiresome, but interactive, innovative gunplay is something unique about games. Not music, not books, not even cinema offers audiences the same ways to get themselves off as games and maybe, for some, that's an idiosyncrasy worth celebrating.

But not when that's all there is; not when the only conversation games are having around violence ends with "it's OK because it's fun."

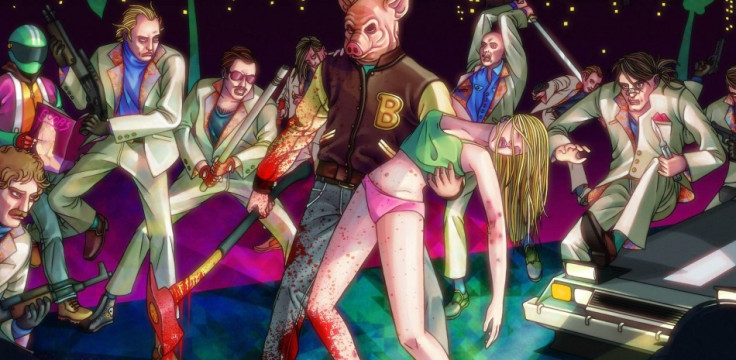

Hotline Miami

Created by the two-man team of designer Jonatan Söderström and artist Dennis Wedin, Hotline Miami is a sickly rebuttal to the mainstream's lazy attitude to violence. Nominated in the Best Audio category at this month's Indie Games Festival, as well as scooping an honourable mention for Best Design, Hotline explores the emotional dark side of killing in games.

It's a bloody, confusing, nauseous story that offers no trite get outs from the brutality it represents. Talking about the mainstream market, Söderström says violent games have grown dull:

"Violence in games is boring; it doesn't evoke any feelings at all. You just feel kind of empty watching all the explosions and everything. It's just not interesting.

"We wanted to show how ugly it is when you kill people. There's a scene in Drive where [Ryan Gosling's] wearing a mask, standing outside a gangster's restaurant, and it looks like he's contemplating going berserk. We ended up doing that scene for a whole game; what would have happened if he had gone berserk?"

Nothing good. Shot from a top down perspective, the violence in Hotline Miami is ugly and red. Shotguns blast people's stomachs open, baseball bats cave their heads in. Nick someone with a pistol and they'll crawl around until you finish them off by slamming their head against the floor; corner them in a back room, and a close-up of their face appears, begging you not to do it.

"There are moral implications in trying to sanitise violence and we just didn't want to do that," continues Söderström. "It's better to make a violent game than to try and tone down the violence. We wanted to show how ugly it is when you kill people."

"And not to make it cool," says Wedin. "It's not like you do a 360 flip or something and cut a guy in half. It's really just bam-bam and he's dead, like in real life."

Bam-bam

Where AAA shooters pride themselves on bigger, gnarlier kills (hence Gears of War's chainsaw gun; the Petrusite evaporator in Killzone 3) Hotline Miami wants its violence to be fast and potent, still emotional but not fun in the traditional sense.

You're just as vulnerable as your victims - that bam-bam uncoolness that Wedin describes works both ways - and if you aren't quick enough, you'll be dead in seconds.

That gives Miami this horrible kind of buzz. You need to be smart and have quick reflexes to get by, meaning that, when you finish a level, you can't help but feel proud. It's not the spectacle or the "awesomeness" that gets you off in Hotline Miami; it's the straight up act of killing people.

And the game eases you into being okay with that. The top down view is one thing, helping remove you somewhat from the bloodshed on the ground, but the one hit-one death dynamic also helps. When you can die so easily, you have to address each level as a kind of puzzle with a correct and very exacting solution to be found. You think of it like "I can kill guy A, pick up the shotgun, run to room 1, shoot guys B and C..." etc. and that diametric layout puts you into, what practitioners of BDSM would call a kind of subspace - an induced mental environment where you're comfortable doing things you might otherwise not be. This was intentional.

"The guy you're playing as doesn't really put any feeling into what he's doing," Söderström explains. "Aside from after the first level where he realises what he's done and vomits, he just does it mechanically; he doesn't really put any feeling into it at all. He's not a martial artist or anything like that."

"We wanted to make a game that looked cool and felt cool when you were playing it like other action games," says Wedin. "We wanted to make a game that you enjoyed a lot but there's always that feeling that what you're doing is very weird, it questions you. Other action games don't do that. They always tell you that some girlfriend has been kidnapped or that the world is going to end and you have to fix it with violence, but in our game, the violence is just there - you don't know why you're doing it."

Aftercare

Game violence has always been sexy and Hotline Miami is no different. The killing is stark, potent and rewarding - orgasmic, if you like - and the pounding soundtrack and steadily increasing score meter act as a kind of Viagra, spurning you on throughout the whole, messy ordeal.

But where a lot of shooters keep that up across their entire length, building to climax with increasing powerful guns and tougher baddies, Hotline takes the autoerotic thrill of killing in games and turns it back on itself.

Sticking with the bondage analogy, every session in Hotline Miami leads into a drained period of aftercare, where you're dropped back into your character's roach-hole apartment and left to come down. These scenes are more nauseating than the violence itself. They give you the space to think about what you just did, dopey music on the soundtrack evoking a hungover disappointment that in your guilty heart of hearts, you know you're feeling

Unlike AAA hits that distract your mind with a constant trickle of bodies to shoot, Hotline Miami wants you to think about killing. With these little downtime bits, it slaps you round the face and asks "remember what you did last night?" Wedin and Söderström deliberately switched the tempo up like this:

"We had some famous artists that we wanted to use for the soundtrack - not mega-famous but kind of famous - and it was hard to get a good deal with them because we didn't have a lot of money when we started working on the game," says Söderström. "So, I just went on Bandcamp and just looked for music I could download that would fit the mood and built the soundtrack around that.

"It's different from part to part, but in the action parts we wanted like a pumping soundtrack, something kind of low tempo so you wouldn't get frustrated, but also something that would make you want to keep playing."

"Something that would put you in a kind of hypnotic state," adds Wedin "The soundtrack keeps your blood flowing."

"Yeah, for the bits in the apartment, we wanted a kind of music that would make you feel like you were a bit hungover from the night before, from the experiences you had. It would produce this kind of nauseating feeling. We wanted to confuse people and also make it so they wouldn't skip through the game; they'd play it again and try to figure out what they had actually been doing. We wanted to make people uncomfortable."

House on fire

And that's the fundamental difference here. Where shooters, historically, have revolved around making you feel good about killing, Hotline Miami wants to make you feel sick. It lays its cards on the table from the off: The homeless guy running the tutorial section, who takes the place of one of Call of Duty's sergeants or something, opens the game with "I'm here to tell you how to kill people" and from thereon it doesn't let up. It's in your face, rubbing your nose in the gore and the death and how much you thought you'd be enjoying it all.

And then it goes one further, and totally outmanoeuvres AAA depictions of violence.

The plot of Hotline Miami is surreal, hallucinogenic and intentionally matted. It purposefully withholds context or reason to see if you'll still keep killing regardless. Spec Ops: The Line, from the mainstream space, does that too but Söderström and Wedin are a little braver. At the end of the game, they pop up as themselves, playing two bored janitors who, as it turns out, have been the ones sending you the assassination contracts just because they were bored.

Where we've had AAA games like The Line and Far Cry 3 attack the player for their violent behaviour, Hotline Miami sets its own house on fire; the people behind the game are the ones, ultimately, behind all the killing.

"I've read about Spec Ops: The Line and it seems to be doing a lot of things similar to Hotline Miami," says Söderström. "The question we wanted to raise with the plot was why are people killing? So, when we discussed adding ourselves in there, it's because people are killing because we made the game. We're responsible for getting people to kill a lot of people.

"Some people get what we tried to do, and some don't. Some people have criticised us for trying to do what we tried to do and failing a bit. They tried to see something else there that we didn't really want to include. Some people think that we should have made it so we were encouraging players to not play anymore, to get the violence to a level where people didn't want to continue with the game. We wanted to do the violence really disgusting, but we wanted to do a good game first."

Is this the power of the indies? With its hypnotic soundtrack, disassociating visuals and sexy violence, Hotline Miami enters the same conversation as the AAA games that question the player's complicity in violence. But then it goes beyond.

Free from the PR tangle that leaves big studios always fighting to save face, it's allowed to point the finger at itself and say, you know what, game developers can be rotten bastards, too.

Across the Indie Games Festival list of nominees, we can see games subverting expectations. Richard Hofmeier's Cart Life challenges the idea that games need always be about fantasy; Anna Anthropy's Dys4ia is a real life story about transgenderism, a subject almost totally ignored by the AAA boys.

But Hotline Miami is just that little bit more powerful. It takes those subversive mainstream sleeper hits that question game violence and subverts them again, implicating developers and players all at once. Söderström and Wedin's game is a frightening vision of the medium at large. It says that, at their core, videogames are all about giggling boys in basements, killing people just for kicks.

So, how many people HAVE you killed since you starting playing games? After experiencing Hotline Miami, you might begin to worry.

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.