Buffy the Vampire Slayer 20th anniversary: How she kicked off kick-ass feminism

Twenty years after it first aired, the show is still a cult hit thanks to its powerful women.

It has been 20 years since Buffy appeared on our TV screens in all her fabulous, vampire-staking, one-liner glory. Funny, feisty and furious, the heroine of the cult TV show was undeniably feminist – and the story of an ex-cheerleader-turned-demon-hunter has an enduring appeal.

The first of its kind in mainstream culture, Buffy turned the decades-old allegory of the helpless, submissive woman on its head. It was – and still is – a celebration of female empowerment and independence.

"It was designed explicitly to counter the tired horror trope of the clueless blonde who wanders into an alley and gets beaten by some demon," says Dr Trisha Pender, author of I'm Buffy and You're History: Buffy the Vampire Slayer and Contemporary Feminism.

"In Buffy, it's the blonde girl who does the beating and she's not clueless at all. Demons in the Buffyverse are always underestimating Buffy's powers, and it is a big part of the pleasure of the series seeing Buffy turn the tables on them."

The show was, undeniably, a product of the "Girl Power" cultural phenomenon – a term of empowerment popularised towards the end of the 1990s. Catapulted into the mainstream by the Spice Girls, the movement found its way into every form of media – including television like Xena the Warrior Princess. It brought to the surface the kind of feminism that had been bubbling below the surface for years, from the underground "Riot Grrl" punk subculture and academic feminist theory, discussed only in certain circles.

As was the case with the Spice Girls and Xena, what we saw with Buffy was a kind of power feminism – an archetypally strong woman trained in martial arts, wielding a stake.

"When we watch Buffy, we experience the vicarious thrill of kicking the bad guys on their asses, time after time after time," Pender says. "It's the primetime panacea for patriarchy – only it's not on primetime anymore."

Buffy tackled contemporary issues

One of the key reasons Buffy still has appeal two decades after first airing is because it tackled a myriad of contemporary issues that still affect women, from sexual assault and addiction to low-paid, part-time employment. Unlike other shows of that era, the show follows Buffy's rocky road from adolescence to adulthood, tackling two types of demons – the "real" ones and her own.

When Spike attempts to rape Buffy in season six, it is a reminder that the majority of sexual assaults are carried out by someone known to the victim. When Buffy works at the Doublemeat Palace burger joint, the story turns to her money problems and the treatment of low-paid workers. When Willow becomes addicted to dark magic, her descent and loss of control mirrors the plight of so many addicts.

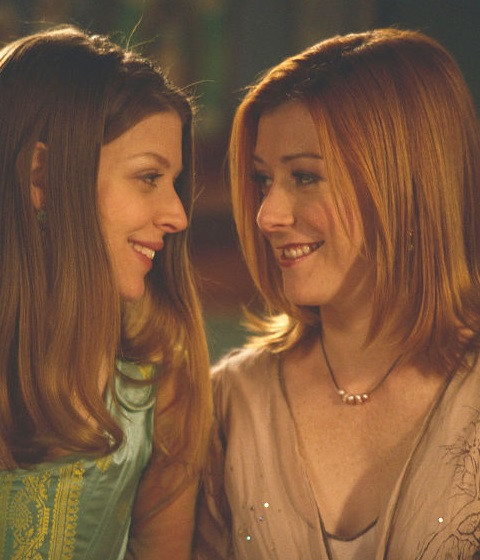

Unafraid to push sexual boundaries, the show delved into desire and orientation, most notably through the romance between Willow and Tara – one of the first lesbian relationships on mainstream TV. It was an open and refreshing change from the male-centric relationships of other programmes – the focus, for once, was solely on women.

The bad guys represent the worst of the patriarchy - and current politics

For Buffy fans, the current political climate in America is familiar. Dominated by vitriol and hateful rhetoric mostly aimed at women, it has – in so many ways – been like living on a hellmouth. Whether it is the now-President bragging about sexual assault to his inner circle or him threatening to curb women's reproductive rights, this blatant misogyny is something Buffy encountered time and time again with her otherworldly nemeses.

The show uses fictional villains to symbolise real-life problems, including manipulation and abuses of power. Buffy fights The Master (a patriarchal vampire), The Mayor (a Bible-quoting promoter of family values) and in the season finale, Caleb (a fundamentalist, ex-priest aptly dubbed "the-Reverend-I-hate-women" by Xander).

In Caleb, who spouts hellfire and damnation with passion, the comparison toTrump is most obvious. For Caleb, women are "dirty" or "whores" – for Trump, they are "nasty". Unlike Trump, whose sexism, racism and homophobia carried him to presidency, Caleb is defeated by Buffy in a profound way – she uses a scythe to cut him vertically from the groin up.

Buffy explored masculinity and gender identity in a way unseen before

What Joss Whedon manages to achieve in Buffy is something feminists continue to push for to this day – turning the binary notion of what is feminine and masculine on its head. Buffy is the superhero because only women can be vampire slayers, as her powers are matrilineal. Her sidekick, Willow, transforms from a shy, bookish friend to a powerful witch. Faith, a fellow slayer, is as tough as Buffy.

The same transformation goes for the male characters. Xander, one of Buffy's best friends, is loyal but afraid. Angel and Spike, the two love interests, are dominant but at the same time passive, as Buffy switches between the two. Giles is Buffy's tutor and mentor, but she soon becomes stronger than him and he is as reliant on her as she is of him.

"Xander Harris, Buffy's early admirer and sidekick, provides one challenge to stereotypes about masculinity," Pender says. "An archetype of 1990s 'embattled masculinity', Xander struggles with the machismo stereotypes of classic narrative film as he negotiates his role as handmaiden to Buffy's Slayer."

The way Pender explores masculinity in her book is through the character of Riley Finn – one of the most reviled of Buffy's suitors, the "cornfed Iowa boy". Ultimately underwhelming, Pender argues his character was created to highlight the dangers of "normative masculinity".

"Riley seems like 'Joe Normal' and Buffy likes him for that, but throughout Riley story arc we slowly learn that "Joe Normal" is something like Buffy's kryptonite," Pender says. "Desiring normality messes badly with the Slayer's mind and mojo."

Buffy's feminism is also problematic

Over its seven-year span, Buffy served as inspiration for an entire generation of women and girls. It brought feminism to the mainstream, but at the same time marked a subculture of its own while playing to a mainstream audience. It was on primetime – and Netflix until last year – and had all the makings of a cult classic: a pretty woman fighting monsters, romance, comedy, horror and drama.

This isn't to say the feminism in the show is flawless, though. There are certainly problems concerning racial representation – Buffy is a white, blonde American in a mostly white, middle-class existence, an issue quite rightly brought up by critics.

But on a more positive note, the feminism embodied by Buffy is a refusal of sexist violence, a fight against the patriarchy and the tensions between individual and collective empowerment (Buffy is strong, powerful, but inherently lonely and isolated) – which are all issues of third-wave feminism. It is about reclaiming the public space for women and challenging their traditionally passive role.

Essentially, Buffy's entire world is constructed around men – and her job is to dismantle the patriarchy. Even the idea of a vampire slayer was thought up by men, which she brings up in her rousing speech to her army of female slayers in the finale.

"Here's the part where you make a choice. What if you could have that power now? In every generation one Slayer is born, because a bunch of men who died thousands of years ago made up that rule. They were powerful men. This woman [pointing to Willow] is more powerful than all of them combined. So I say we change the rules. I say my power should be our power. Tomorrow, Willow will use the essence of the scythe to change our destiny."

But what makes the show so watchable is how, as an icon of the Girl Power movement, she makes the position her own.

"From now on, every girl in the world who might be a Slayer will be a Slayer. Every girl who could have the power will have the power. Can stand up? Will stand up. Slayers—every one of us. Make your choice: are you ready to be strong?"

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.