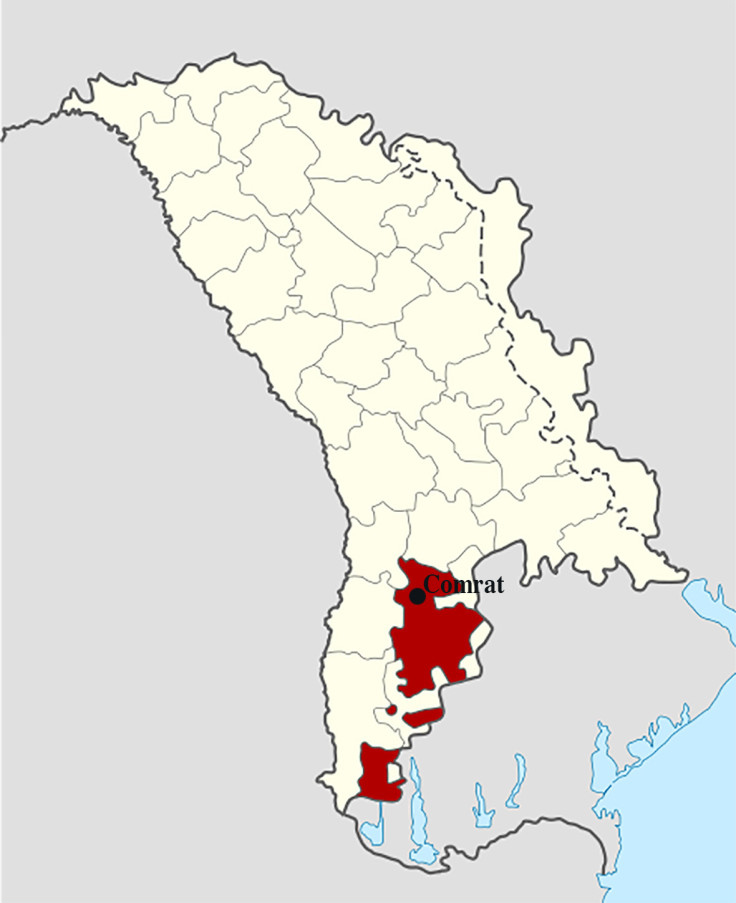

How Gagauzia, a tiny corner of Moldova, became the front line in Erdogan and Putin's war for influence

Gagauzia attracts investment from both Turkey and Russia by playing them off against each other

It is hard to walk Comrat's shattered footpaths without seeing the standards of patrons set against the sky – the streets of the tiny capital of Moldova's Territorial Autonomous Unit of Gagauzia are lined with foreign flags, betraying its reliance on external donors.

Even as much of the focus on in this part of the world falls on the frozen conflict in Transnistria, the Gagauz, a rural Turkic-Christian people numbering around 160,000, are very much courted in the post-communist world of patrons and clients.

On a side street of Strada Lenin, the Recep Tayyip Erdogan Nursing Home demonstrates the presence of one of Gagauzia's major suitors, as the influence of another, Vladimir Putin's Russia, is everywhere.

Cosmas Shartz, an American Orthodox-convert monk with a smudge of white hair, bridges both. Shartz, who discovered Gagauzia in a footnote of a book on Turkish grammar, now lives in Comrat and spends his time translating Russian scriptures into the fading tongue of Gagauz – which he describes as like "Turkish backwards."

"The Gagauz have always been a double minority," he said. "There's a thing called sleeping beauty nationalism, where they're suddenly woken to their identity and place in the world."

There are at least 21 different academic theories as to Gagauz origin. Thought to be descendants of Oghuz Turks in modern-day Kazakhstan, who fled inter-tribal warfare for Bessarabia in the medieval Bulgarian kingdom, their conversion to Orthodox Christianity suggests they arrived in the region before the Ottoman conquest in the 14th century.

When the Russians conquered Bessarabia in 1812, they forcibly deported the local Sunni Nogia people, moving in the Gagauz from Ottoman-controlled eastern Bulgaria. A peasant uprising in 1906 saw Gagauz's only full independence, five days of freedom as the Republic of Comrat.

Gagauzia: playing all sides.

Tsarist forces swiftly regained control, before the Bolshevik revolution saw a brief Moldovan sovereignty. The end of the first world war saw Moldova absorbed into Romania until the Soviets began re-conquering Eastern Europe in 1944.

But while much is known about Russia's leverage over its former countrymen, Turkey's regional influence is vastly understated. In the aftermath of the collapse of the Soviet Union in December 1991, the Turkish International Cooperation and Coordination Agency (Tika) set up offices in the new republics of Azerbaijan, Kyrgyzstan, Kazakhstan, Uzbekistan, Tajikistan and Turkmenistan.

Primarily focusing on education and infrastructure, TIKA doubled in size in the decade after Erdogan came to power as prime minister in 2003. Now Gagauzia serves as a testament to the role of Turkish soft power.

"We have two strategic partners. Turkey is good for business, Russia for access to the market," said Foreign Minister Vitali Vlah.

In 1991, the Gagauz declared independence as Moldova appeared to be inching towards reunification with Romania. The Russians supplied the guns in the brief civil war but it was Turkish President Süleyman Demirel who got the parties to the table in 1994.

"They played an important role in getting us independence, they've helped us for a long time," Vitali Vlah says: "Everything here is built by Tika."

It's not a clash of loyalties but a neon sign: open for business. Infrastructure from manhole covers to government buildings host dedications to Tika, and the growing number of Turkish schools celebrate Ataturk's birthday and fly red crescent flags. An embassy has recently opened in the yolk of Comrat, a minutes walk from the Orthodox cathedral that dominates the town.

Vitali Vlah is a distant relation of governor Irina Vlah, "known locally as the selfie governor," according to Shartz. "There was a campaign to have her named Woman of the Year for Russian magazine Aquarelle, a Vogue type of thing."

Self-sufficient in food and wine, the Gagauz are by no means wealthy, rather able to wait it out for money and infrastructure from the Turks, Russians, Moldovans, and European Union. Their business is neutrality, shaking down patrons seeking influence for its own sake, a griftocracy landlocked by oligarchy.

"Gagauzia is playing all sides," says Nadejda Guseinova, manager of Miras Moldova's Gagauz wing, a charity that receives a small amount of money and assistance from the European Union. "Crisis is for the ordinary people, not for the rich."

Road worker turned militant leader Stepan Topal, elected the first and only president of Gagauzia before the 1994 autonomy agreement, remains embittered by relations with the Moldovan government. "What the Europeans call democracy isn't real democracy," he says, speech weaving between Russian and Gagauz. "We were supposed to advance, and it hasn't happened."

"In the future, Turkic people and nations are going to rise up and become more important," Topal adds. "The Turkic brotherhood is an ancient race, like the Jews."

It's better to be dead. Everytime you go to a doctor, you have to pay - twenty leu, fifty leu. The average salary in Gagauzia is maybe 2,000 leu per month.

Russian has spiked the Gagauz language, yet after the peace deal, the language moved from Cyrillic to Latin script, in line with their ethnic cousins. "There was help coming from Turkey," explains journalist Dmitrii Popozoglo, contributing editor at Turkish-funded newspaper United Gagauzia. "But the older people could read it in Cyrillic. After we turned to Latin, the young people didn't learn to read it, and the old people can't read it, so no one reads it," he said.

"Pop culture to preserve the language is the only way," says Shartz, as he takes me to the studio of Vitali Manjul, whose sculptures feature in the central park and who makes music that ranges from rap to rock to folk. "The important thing is for us not to be lost. The large countries are working to devour the small ones. We are like children looking at our parents," he said.

But culture alone cannot sustain power, and it is rumoured that sanction busting for Russia is the engine of the Vlah administration, bootlegging cheese and other banned products from the West into Russia under the Gagauz flag. Around sixty percent of the region's legitimate income comes selling wine by the truck to the Italians, packaged to foreign consumers as 'bottled in Italy'.

After graduating high school, many young people flee to study in Transnistria. Nadejda Guseinova was dissuaded from studying medicine by her family because of the expense in paying off university staff to pass exams. "Hospital is the most corrupt place in Moldova," she says, "and medical university is even more corrupt. They pay €50 minimum to pass an exam, and have six to seven exams [each year], and it goes up for every extra ten marks."

"It's better to be dead. Everytime you go to a doctor, you have to pay – twenty leu, fifty leu. The average salary in Gagauzia is maybe 2,000 leu per month."

Vera Chimpoyesh, Director of the university library, remains nostalgic for the certainty of communism. "There was a lot of money in the collective farms, people didn't have to leave," she says, echoing the feelings of many of the older generation.

Life since the end of history in the former Soviet Union has seen the development of post-ideological political system, an intractable theatre where the only values are power and the art of the deal. Increasingly, Erdogan's leadership has steered Turkey towards the Russian elite's worldview.

"We took the good out of each," Vitali Vlah assured me when we met. But in the shadow of the Putin-Erdogan rapprochement, the question for the Gagauz, and for the region, is what good can come of the two powers joining together on the same side?

Elle Hardy is a freelance writer and photographer focusing on dictatorships and the republics of the former USSR.

© Copyright IBTimes 2024. All rights reserved.