How Milton Keynes scientists are training dogs to sniff out cancer

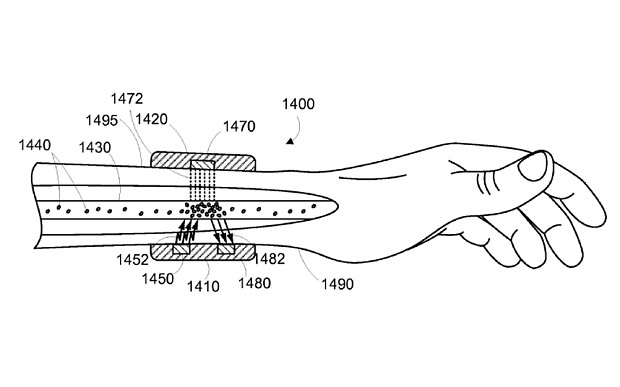

With news that Google is developing a wrist-worn device that transmits energy to cancer patients, it is clear that the fight against humanity's greatest nemesis is becoming ever more sophisticated, with mutinationals wading in to hurl space-age technology at the disease.

Yet, of all the techniques currently being developed against cancer, perhaps the most interesting is being honed by a group of scientists in Milton Keynes, a city not always known for originality. In terms of complexity, it is the antithesis of Google's energy watch, involving a resource which has been at man's beck and call for thousands of years yet may possess a remarkable ability which has lain undiscovered until now.

The researchers believe that dogs, yes dogs, can detect cancer. They say the disease has a unique odour, and our faithful quadruped friends can use their 300 million smell receptors to sniff it out.

The Milton Keynes scientists varry out the research under the aegis of a charity called Medical Detection Dogs, and they currently have a total of 15 dogs in training. Other groups are doing similar work in Italy, Japan and the United States, and, according to MDD researcher Dr Claire Guest, the studies are now at an advanced stage.

"It's been going on for 10 years," Guest tells IBTimes UK. "The first study [on cancer-detecting dogs] was published in the BMJ in September 2004 and since then there've been a number of studies around the world that have achieved peer review publication. The body of evidence is now growing that cancer has a unique odour."

The research essentially has two key objectives: to harness the potential of dogs to provide second-line screening for cancers that are currently very difficult to diagnose reliably, such as prostate cancer, and to develop electronic systems, or 'e-noses', which will mimic the dogs' behaviour and automate it.

Guest says cancer's unique smell is attributable to the fact that cancer cells divide differently to healthy cells. She says she has "no idea" what the smell is actually like, but insists the dogs can pick it up loud and clear.

During the tests so far, Guest says, "the dogs had a sense this smell was abnormal and potentially dangerous. It could be an instinctive response but the dogs were clearly able to detect and concerned about the odour. Ancedotally, the dogs would persistently lick or nudge or stare at the owner and even the region where the cancer was."

The MDD team are now introducing their dogs to cancer samples in a specialist training area, and the dogs are being trained to sniff it out. Guest and her fellow researchers are teaching the dogs to sit and stare at the cancerous cells and move away from those which are non-malignant.

All tests are being conducted under double-blind conditions; the trainer is not visible to the dog in the room when the samples are being sniffed, and in fact the trainers themselves don't know where the samples are.

How accurate are the dogs' reactions? "It's not 100% accurate, like any system there's never 100% reliability" Guest says.

"Our dogs work in the low 90% bracket. Some publications indicate dogs can do it even better than that, although I'd be fairly cautious. My estimate would be that operationally dogs would be between 85% and 90% accurate."

And which dogs are the best at sniffing out the cancer? "A lot of gun dogs, a lot of working dogs are particularly good at this" Guest says, although a number of different breeds are being trained. "They all live out with fosterers, and they have a normal doggy life in the evening," she adds.

Despite all the advances she and her team have made, Guest is cautious when asked how quickly the dogs can be brought into active service as cancer-sniffers.

'My estimate would be that operationally dogs would be between 85% and 90% accurate in detecting cancer.'

"All the work is in research, so, although lots of journals are suggesting that in double-blind studies it shows that dogs can detect cancer, clearly it has to be processed through the evidence base before it could be rolled out as a possibility.

"We are a charity, we want to help save lives as soon as possible. We'll be screening thousands of samples over the next three years, then we'll accept whether it will be an acceptable service to offer. The more support we get the more quickly we will be able to publish results."

If and when the technique of using dogs is rolled out on a commercial scale, will its use be widespread?

"That depends on how much medics feel it's of value," Guest says. "The general public are saying they would be very happy to have a sample sniffed by a dog. Certainly, over the last few months, there's been a lot more interest in our work, and there's a growing body of evidence behind it."

Over the course of human history we've trained dogs to perform all manner of crucial tasks, from guiding sheep to sniffing bombs, pulling sledges to guiding the blind. Yet perhaps their most crucial task is still to come.

For more information visit www.medicaldetectiondogs.org.uk

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.