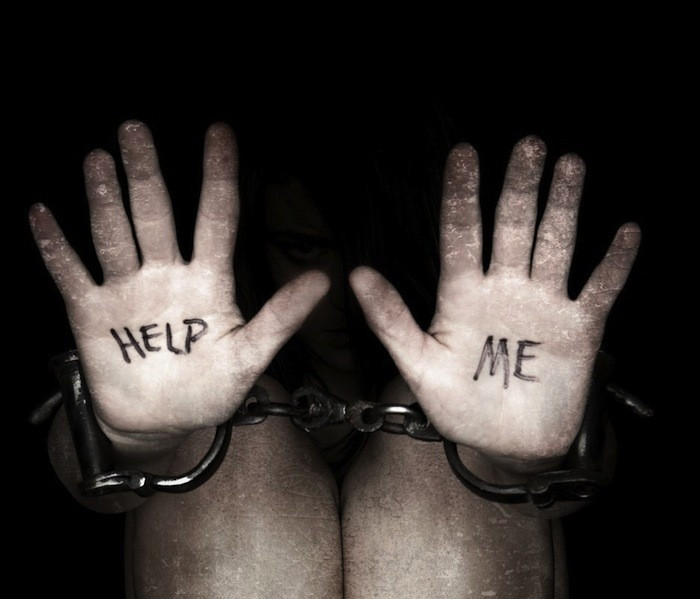

Human Trafficking: Why Slavery Still Exists

Last week, Steve McQueen's political drama 12 Years A Slave won three awards at the Oscars, including the coveted Best Picture.

The scenes of brutality and degradation in the ground-breaking film were hard to watch, forcing many members of the audience – including myself – to turn away. Yet the issue of slavery is nearly as much of a problem today as it was in 1841, when Solomon Northup was kidnapped from his home.

As many as 21 million men, women and children are trafficked within their own countries and across international borders in the 21<sup>st century, to be sold as forced labourers, sex slaves, for forced marriages and as child soldiers.

Kevin B Bales, consultant to the United Nations Global Trafficking Program on the Trafficking of Human Beings, states that one of the reasons slavery still exists is because of the concept of dehumanisation.

At the 2014 King's College London conference on Organised Crime in Conflict Zones he described dehumanisation as the "creation of a sub-human species which amounts to the justification and rationalisation behind slavery". This concept, which is widespread in countries experiencing conflict, is largely driven by political and economic instability, he said.

In some cases, people are taken from their homes by force, or lured against their will under the false pretence of finding legitimate work.

Others – including farm workers, factory workers and domestic labourers – are introduced into the network of trafficking by force, fraud and coercion.

Speaking at the event, Parosha Chandran, a human rights lawyer at 1 Pump Court and co-founder of the Trafficking Law and Policy Forum, told the harrowing story of a young girl known as "M".

Born in northern Uganda in 1989, M was left with her stepfather after the death of both of her parents. She was sexually abused for years, eventually giving birth to his child at 15. When the Lord's Resistance Army purged the village, everyone – including M's stepfather – was slaughtered. M hid in a cupboard. The few survivors were systematically raped by the military personnel in the nearest camp. In order to protect herself, M allied herself to her attacker; a soldier who declared his love for her weeks later. He took her to the city, where her child was taken away. She was eventually put to work in a brothel and trafficked to the UK at the age of 17.

Legislation against trafficking, while of some benefit, is still of limited use.

In December 2013, Home Secretary Theresa May proposed the Modern Slavery Bill to tackle the problem, which will come into effect later this year.

War crimes tribunals, military tribunals and truth commissions offer retributive justice. However, according to Lynellyn D Long, chief of mission at the International Organisation for Migration in Bosnia-Herzegovina, the only way to address the problem is by tackling the underlying political and economic problems in target countries.

Long is also the chair of trustees at Her Equality Rights and Autonomy (HERA), a charity which promotes the economic autonomy of trafficked women.

Speaking to IBTimes UK, she said: "You have to try and get to the underlying causes, such as political insecurity and most of all economic insecurity. That's why my own work is focused on providing grants to women's enterprises so that they can basically have a choice as to whether they want to emigrate or not. As soon as they emigrate, they can fall into the hands of traffickers.

She added: "In a conflict situation, you can pretty much predict the economic situation will be particularly fragile. The basic goods and services will be contested so at that point, trafficking really mushrooms. Women who want to enter the labour market and find jobs are targeted – so I think we should be focusing on this issue. The legal issues are very important, but they really are the end of the line."

Decriminalising prostitution, using the Nordic Model, is of limited use in eliminating sex trafficking. While some argue women are discouraged from coming forward about their situation – as prostitution is a crime – Long says the two-tier model of legal and migrant prostitutes will still be a problem.

She told IBTimes UK: "I think it would help, but on the other hand, in countries where they have completely decriminalised prostitution, we have had this two-tier model of whether you are an immigrant or a 'legal' prostitute. It's not clear that decriminalisation alone will make a huge difference. An abolitionist approach is good in terms of the demand side, but aren't obvious solutions."

The prosecution rate is low for traffickers. Organisations such as HERA offer women who are released from their captors a chance to regain control of their lives. Trafficked individuals are offered shelter, food and psychological support, but most importantly, they need to find a legal income.

Long said: "The thing they most need is to earn a living and become independent. Very generally, we have found women who have been through these experiences have a very entrepreneurial outlook on life. They are savvy. They want to become economically autonomous and some of them make very good businesswomen."

Even though today's slavery is less blatant and brutal than the slavery of the past, it does not make it any more acceptable. Organisations such as HERA, which provide legitimate economic alternatives, along with anti-trafficking laws and awareness, are just a few ways to eventually eliminate this problem.

The KCL conference was organised by postgraduate Security, Conflict and Development students.

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.