Ian Livingstone Says Teachers 'Not Equipped' for ICT Curriculum [VIDEO]

As the government prepares changes to the IT curriculum, Ian Livingstone CBE explains the new changes and how they will affect children.

Starting from 2014, the Department of Education will introduce a revamped ICT curriculum, focusing less on office skills and more on programming. Spearheaded by industry and government research, the new classes will be a major shake-up of how computing is taught in schools.

Anyone reading this aged between 20 and 30 is bound to remember the relentless dullness of ICT classes, the most dreaded point in the school timetable (with the possible exception of swimming lessons) for most kids in the nineties and noughties. Learning about computers at school meant sitting, listening, while a vaguely bored man in a tie droned on about Excel and PowerPoint and other dull programs that everyone already knew how to use.

The problem with school ICT lessons was that they prepared children for a limited and frankly uninspiring range of careers. Classes focused on office-based tasks like word processing and putting together spread sheets, rather than on creative and potentially more lucrative skills like programming and animation.

Gradually, as computers have permeated every part of student's lives, the IT curriculum has become stagnant and irrelevant.

With the advent of iPads, laptops and social networking the basic office skills the curriculum preaches are as pervasive amongst schoolchildren as the alphabet or multiplication. If the ICT curriculum is going to continue to be a fundamental part of children's education, it needs to teach them how to how to distinguish themselves in burgeoning digital industries like computer games and visual effects.

As Eidos life president and Games Workshop owner Ian Livingstone CBE puts it, "the ICT curriculum needs to teach children how to write as well as read."

"[Children are] learning how to use other people's technology, but being given no insight into how to make their own technology.

"The basic premise for me was rather than someone just playing Angry Birds, let them learn how to make Angry Birds. And coding doesn't just affect the game industry - it's all the creative and digital industries. Whether it's fighting cybercrime, helping build a jet propulsion engine or writing financial services packages, code is core to everything in the digital world that children live in today."

Next-Gen

Co-author of Next-Gen, a pioneering review of the British ICT curriculum from 2010, Livingstone has been instrumental in re-shaping ICT lessons in schools to suit modern-day children. The 20 recommendations laid out in Next-Gen aim to revamp not only the school curriculum, but also the game industry's relationship with educational institutions, by having computer science taught as a compulsory discipline in schools and a database of industry career resources established online.

Following the publication of Next-Gen, the BCS (the Chartered Institute for IT) and the Royal Academy of Engineering drafted a new version of the ICT curriculum based on Livingstone and Hope's proposals. Under the new education system, school children between the ages of five and seven would learn about algorithms and begin to write basic programs.

At Key Stage 2, children aged seven to 11 would be able to make more complex programs and understand how internet search engines find and rank results. Secondary school students in Key Stage 3 would begin to learn about hardware, as well as writing even more sophisticated programs based around solving real-world problems.

Finally, Key Stage 4 children, those aged between 14 and 16, would be taught the "ethical, legal, social and environmental consequences of information systems", examining how digital content affects and is used by people. It's a totally restyled ICT curriculum that, as of February 2013, has been adopted by the government and is now up for public consultation, allowing teachers to flag up any potential issues.

"I'm delighted that recently Michael Gove, secretary of state for education, agreed with these suggestions and computer science is going to be included in the new ICT curriculum, which will be re-branded as 'computing'," says Livingstone.

"The important thing there is that it's a verb; it's getting people to make technology not just use technology, so we have digital makers not just digital users. There are a lot of opportunities out there, and not just in coding...This is a distinct, profitable sector and should be seen on par with pharmaceuticals and financial sectors."

Teachers

Livingstone says that the new curriculum will come into "full force" in 2014, but admits there's a lot of work to be done. Based on the findings in Next-Gen, only 22 percent of current ICT teachers believe they are capable of writing even basic computer programs, while only 19 percent of ICT teachers have a relevant degree, a higher degree or equivalent qualification. For comparison, it should be noted that across all subjects, the percentage of teachers with a relevant degree is just 32 percent.

Asked whether the existing staff of school level ICT teachers would be equipped to handle the new computing curriculum, Livingstone said: "Sadly not, no."

And it's not just in schools. According to the Next-Gen report, only 12 percent of graduates from university game design courses find industry work within six months of graduating:

"We mapped out 144 university courses that had the word "games" in their title, and sadly only 10 of those were found to be fit for purpose," said Livingstone. "A lot of them were generalists, with all the hard skills stripped out of them so they could get bums on seats, and that's really doing a disservice to all the students applying to them who thought they were going to get a job in the game industry when they graduated. And they won't, because we need people who can do stuff rather than just talk about stuff that they want to make."

The recommendations made by Next-Gen vary from offering highly-qualified computing teachers the same "Golden Hello" bonus afforded to maths teachers, to laying out a more vigorous process of accreditation for university courses. Livingstone believes the resources are already in place to retrain ICT teachers, it's just a case of rolling them out:

"There has to be more work from government in terms of creating a teacher training program and a professional development program in terms of assisting ICT teachers. But, we can't afford not to do it. There's an organisation called Computing at School and they've got about 1,500 teachers who are able and willing to act as 'centres of excellence' to help train and retrain existing IT teachers, but there are of course 25,000 school teachers in the country, so there's a lot of work to be done."

Livingstone adds that the resources are already in place: "In schools everywhere there are computers, networked, all capable of programming, it's just that they've always been locked down. It's just a matter of retraining existing resources and teachers. This is nothing new. Thirty years ago the BBC Micro was the cornerstone of computing in schools and in the home, everyone had an affordable, programmable computer in the shape of the Spectrum. So, it's no surprise that things like the game industry came out of this very creative period of technology. But that got all locked down over time as we became passive users of technology."

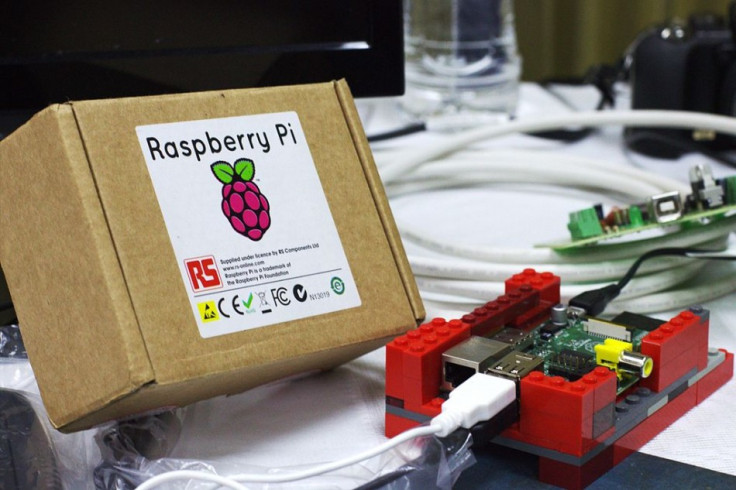

Helping to change this way of doing things are iniatives like the Raspberry Pi, a £25 computer that you can plug into the TV. Google recently announced it will give away 25,000 Raspberry Pis to schools around the country and according to Livingstone, for £15 million you could give a Raspberry Pi to every child in the country.

"I'd also make the recommendation that we have informal learning be as important as formal learning, and that the children and the teachers can learn together. There are so many online resources out there; you can learn from the best online and then, in the classroom, teachers and children can effectively collaborate to do their homework together until formal learning can take over," said Livingstone.

Pervasive

Whether the new computing curriculum points to any job losses among ICT teachers is unclear. Reading Next-Gen, the BSC's proposed curriculum and the Department of Education's response to ICT reform, it's clear that a lot of people, within industry, education and government agree that how computing is taught in the UK needs to change dramatically. But as Livingstone says, that will hopefully mean retraining rather than replacing the people currently working in schools and universities.

What is clear, though, is that the government is beginning to see the financial potential of industries like videogames. Long marginalised by the popular consciousness as a niche reserve among young men, videogames nevertheless generated revenue of £2.9bn last year, according to figures gathered by Develop and Livingstone says they will be a vital industry for Britain going forward:

"Games used to be played by, predominantly, teenage boys in their bedrooms, that was the archetypal assumption of how games were played. Now, they're pervasive.

"President Obama recently cited that it was Mark Zuckerberg's interest in computer games that got him into coding, and the output of that was creating Facebook. Games technology is pervasive and is really an asset to this country.

"The creative industry in particular can help the UK economy going forward as traditional ways of making products and services are being outmoded by the digital world in which we live. If we are a natural created nation, and I'd argue, we're perhaps the most creative nation in the world, we have to give children the schooling to release that creativity."

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.