The Imitation Game: Bletchley Park and the Computers That Helped Alan Turing Break the Nazi's Enigma [Photos]

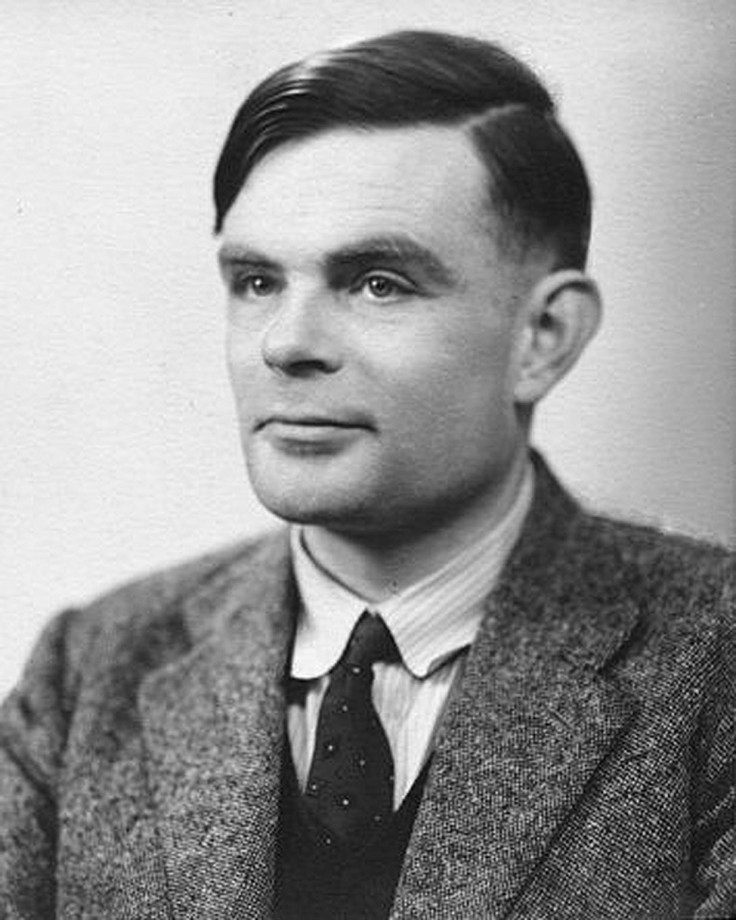

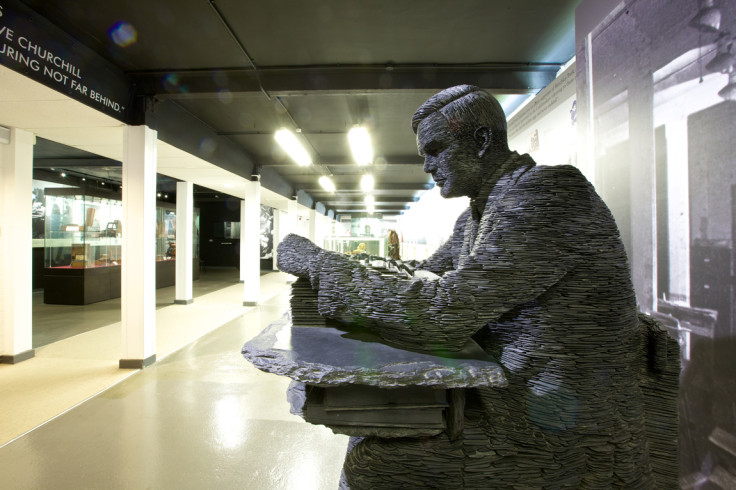

The new British historical thriller film The Imitation Game comes out in cinemas in the UK this Friday, starring Benedict Cumberbatch as Alan Turing, the brilliant mathematician who cracked the Enigma code used by Nazi Germany, ultimately helping the Allies win WWII.

But where did all the magic, or rather, bloody hard work happen? Join IBTimes UK as we take a look around Bletchley Park and the National Museum of Computing in Milton Keynes, Buckinghamshire, where the UK's Government Code and Cypher School (GC&CS) had its base during the war.

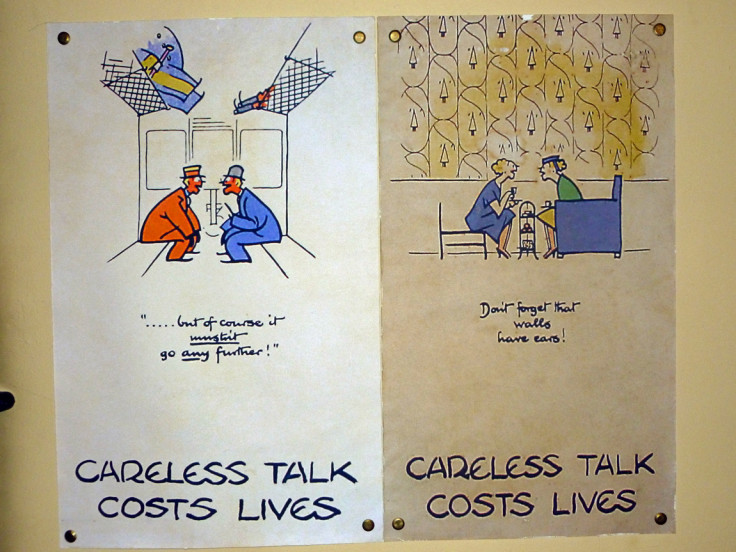

Boasting a mansion and 58 acres of land, Bletchley Park used cover names such as Station X, the Government Communications Headquarters and the London Signals Intelligence Centre.

The site was chosen because there were good train links connecting Oxford and Cambridge universities to the area, as well as good railway links to major cities, and high-volume communication links nearby at Fenny Stratford's telegraph and telephone repeater station.

Initially, all operations were contained in the mansion and its neighbouring cottages, headed by Commander Alastair Denniston and a team of linguists and cryptanalysts.

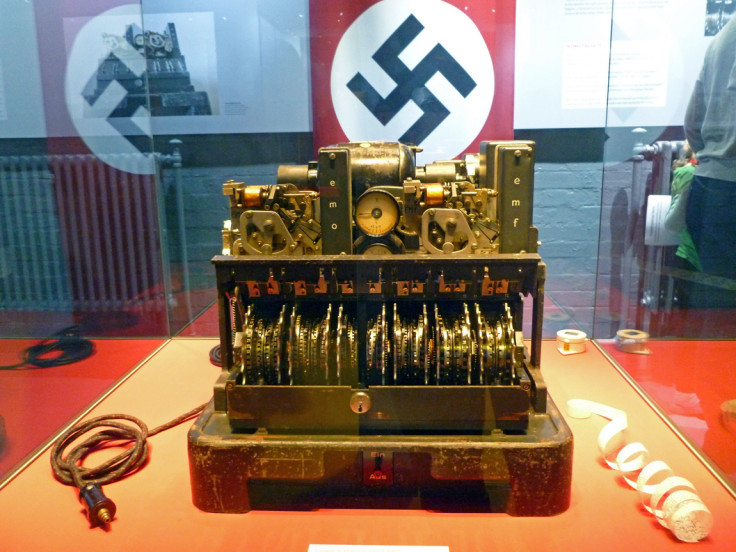

Denniston soon realised that Germany's use of electromechanical cipher machines, such as Enigma, would require the help of trained mathematicians, so after Britain declared war on Germany, he began recruiting a wide range of learned people from Oxford and Cambridge, including professors, mathematicians, chess champions and historians to work at GC&CS.

One of those people was Alan Turing from Cambridge, and in the early part of the war, he worked from the stable yard cottages in Number 3 Cottage on deciphering the coded messages intercepted by British intelligence.

The ground floor of the mansion was used for the naval, military and air sections of the GC&CS, together with a telephone exchange, teleprinter room, kitchen and dining hall, while the top floor of the mansion was given to MI6.

The cottages

Turing's office was in Number 3 Cottage, and a recreation of his office at Bletchley Park today shows he had a number of rather unusual habits – he would chain his mug to the radiator and, having very bad hay fever, it would not be uncommon to see him cycling to work along the countryside wearing a gas mask.

He would practice his speeches out on "Porgy", a teddy bear he bought himself as he never had one as a child, which wore a romper cast off by his niece.

Near the cottages stands a memorial to Marian Rejewski, Jerzy Różycki and Henryk Zygalski, three mathematicians of the Polish intelligence service. In 1938, the Polish post office service intercepted a package for the German Embassy in Warsaw.

Realising it contained an Enigma machine, the post office tipped off the Polish secret service, which took the cipher machine apart, made notes and then put it back together and sent it to the embassy.

Using the information from the interception, Poland's Cipher Bureau were able to reverse engineer Enigma to understand how it worked, and sent the British a clone of the machine in August 1939. Their information and techniques contributed greatly to GC&CS success in decrypting Enigma messages.

The Huts

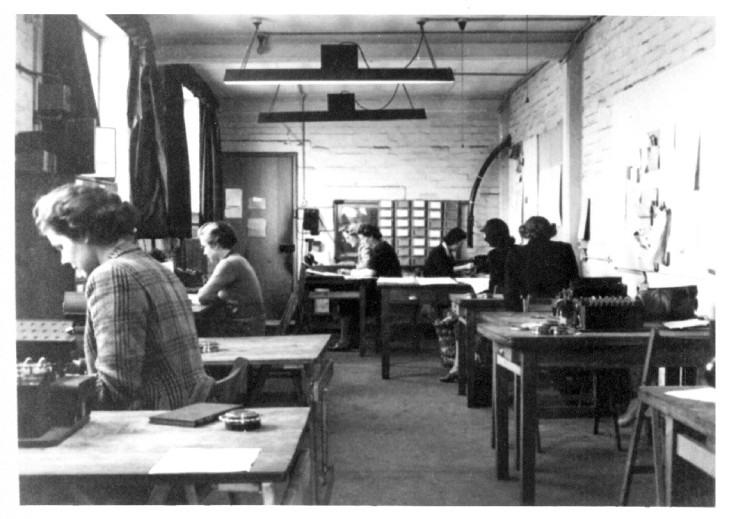

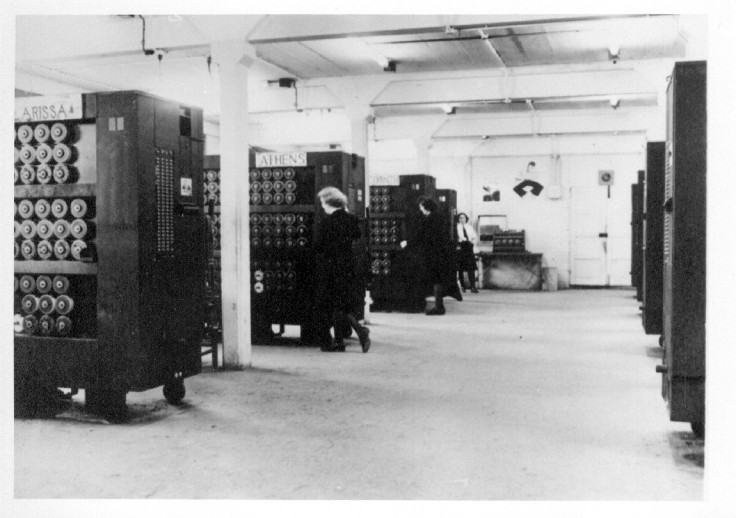

Over time, as the war efforts progressed, the number of staff working at Bletchley Park grew and wooden huts were constructed to house them all.

By 1944, there were roughly 10,000 men and women working at the site but the hours were very long and the working environment in the huts very cold.

Riders would bring in intercepted messages from listening stations in London and other parts of Britain.

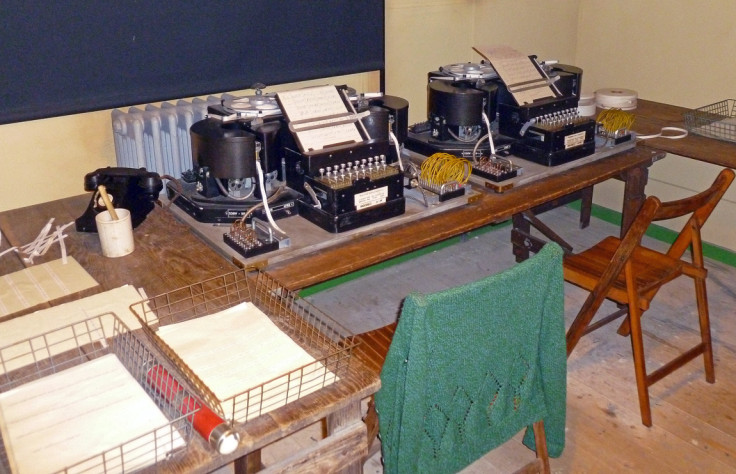

The traffic would be analysed, entered into a machine Turing invented called the Bombe (more on that below), which would decode the messages and give all possible Enigma settings, after which the settings were entered into the TypeX machine to decipher the German text, and then the intelligence was gathered and analysed.

Hut 6 was meant for cryptanalysis of army and air force Enigma messages, which were then translated and analysed in Hut 3. Turing was in charge of Hut 8, where he headed cryptanalysis of naval Enigma, which no one was looking into at the time. It is at Hut 8 that Turing met cryptanalyst Joan Clarke (played in the Imitation Game by Kiera Knightley).

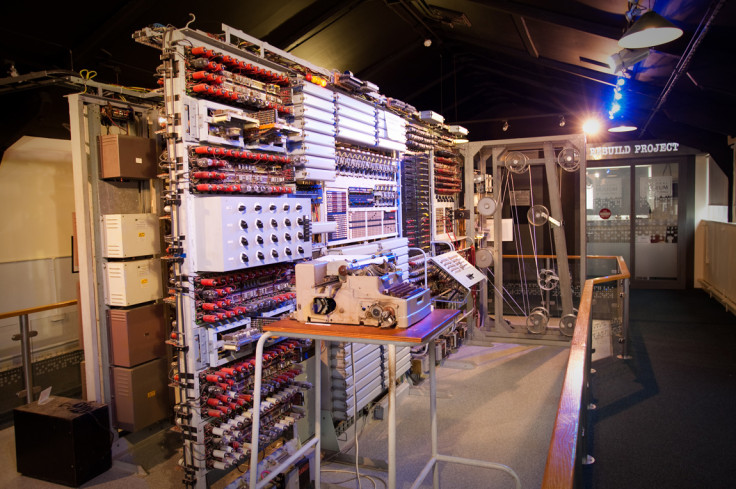

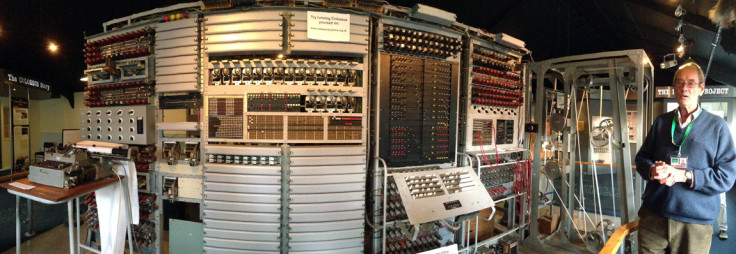

The Bombe and other early computers

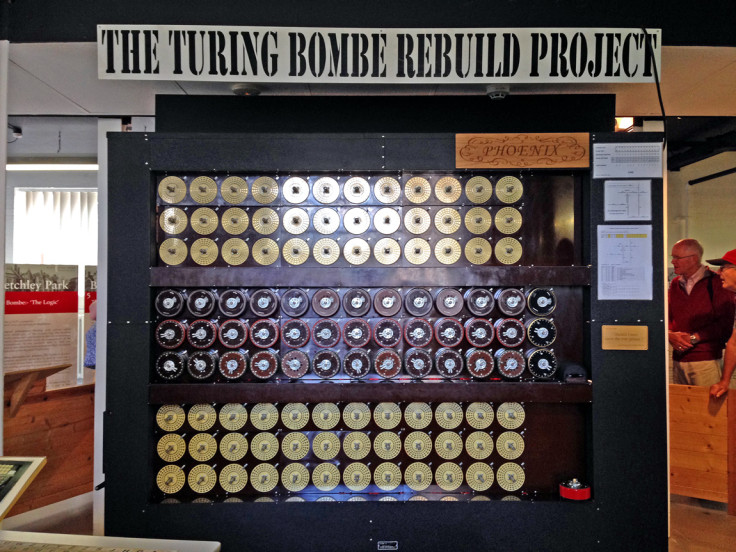

Turing was highly influential in the development of computer science, and his design and theoretical work with fellow cryptanalyst Gordon Welchman for the Bombe was instrumental in helping British intelligence discover what the Germans were planning.

The Bombe was an electromechanical machine that searched for possible correct settings in an Enigma message by emulating the wheels on an Enigma machine. The rotors in the Enigma could be set to one of 26 positions, connected by 26 wires that related to the letters of the alphabet.

When a message was typed in by an operator, a varying electrical current passed through the rotors to encrypt each letter.

Turing's machine was designed to replicate this process, and each vertical set of drums – coloured orange, black and yellow – corresponded with the wiring of each wheel.

When the machine is in motion, the top drums of each three wheel set (i.e. the top horizontal row of drums) would rotate continuously while carrying out 26 electrical tests.

Every time the first row completes 26 tests, then the second horizontal row of drums would move by several notches, and the third horizontal row of drums would only move one notch in every rotation of the middle drums.

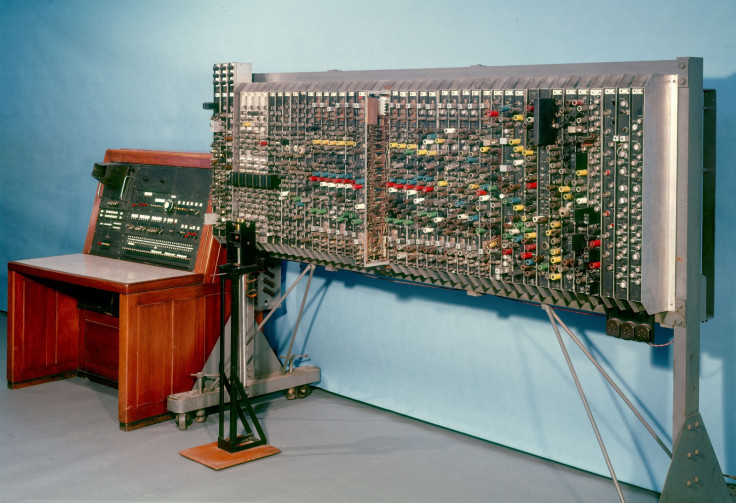

But this is not where the story ends. Turing continued to research techniques for deciphering messages from successive cipher machines used by the Axis powers, including the Lorenz rotor stream cipher machines.

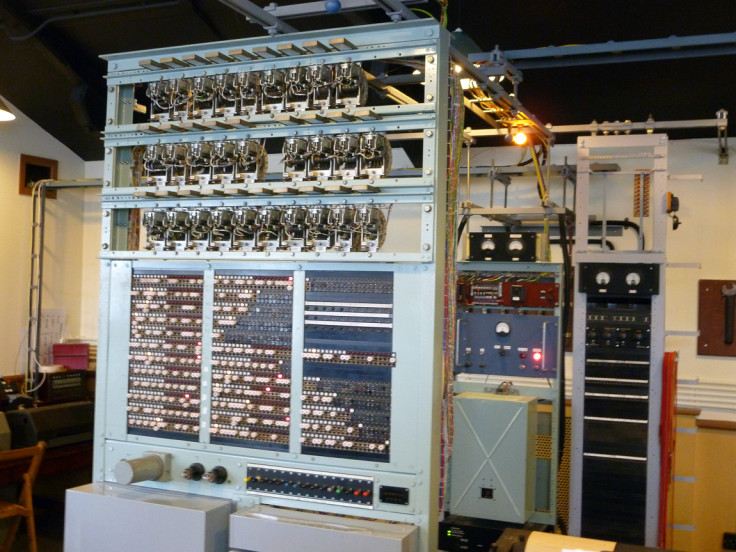

In 1942, Turing devised a technique named Turingery, which was used to decrypt Lorenz messages on the Tunny Machine, a teleprinter rotor cipher attachment that monitored encrypted wireless telegraphy traffic.

Once the start wheel positions of the Lorenz machine had been worked out by cryptoanalysts, this information could be fed into the Tunny machine and the original message could be deciphered quite quickly, but working out the start wheel positions was the hard part and had to be painstakingly done by hand.

So Turing introduced the team working on the Tunny to a Post Office engineer called Tommy Flowers, who then went on to build the Colossus in 1944, the world's first programmable digital electronic computer.

The Colossus was crucial in accelerating the code-breaking effort at Bletchley Park as it fully automated the process. It could work round the clock to figure out the start wheel positions, which could then be fed into the Tunny Machine to decrypt messages much more quickly.

Like the Bombe, Colossus emulated the Lorenz cipher machines, and the machine had to complete two important tasks – "wheel breaking", where pin patterns for all the cipher wheels were discovered, and then it had to use logic to perform "wheel setting", where the start wheel positions could then be discovered.

Once the machine figured it out, it would print out the information on message tape, which could then be fed into the Tunny Machine.

It is estimated by historians that the code-breaking work of Alan Turing and his colleagues shortened the length of the war by two years, and the advances they made into modern computing during and after the war helped to set the foundations of computing today.

For more information about Alan Turing, besides visiting Bletchley Park and the National Museum of Computing, you can also check out the Pilot Ace Computer on show at the Science Museum's new Information Age gallery, which looks at the last 200 years of how communications technology has transformed our lives.

Photos contributed by Dr James Hamilton and Shaun Armstrong.

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.