Inside America's deadly opioid crisis: 'It feels like a horror movie'

Americans are hooked on painkillers and it is tearing families apart. Who is to blame for this crisis?

Rosemarie Iacono thought that America's opioid epidemic was something that happened to somebody else.

Until it happened to her.

All four of her brothers got addicted to painkillers and two of them, Anthony and Raymond, overdosed within 16 months of each other. Iacono spent her teenage years growing up in a household where she was in constant fear that one of them would die.

Now 27, she told IBTimes UK that she went through so much turmoil that for her it felt like she had been an addict too. The nursing assistant, who lives on Staten Island in New York, said that it was a "very hard process because it's not just the addict that's involved". She said: "This is a family disease and it affects every single person in your life. Your mother, your father, your girlfriend and your siblings."

Anthony and Raymond Iacono are two of the 52,000 people who die each year from overdoses from painkillers, heroin and other opioids in America, according to the Centres for Disease Control.

The epidemic is the largest public health crisis in the country and, for those who are fighting it, the largest crisis facing the country, period. The statistics are staggering; far more people are killed by overdoses than gun deaths, which claimed 36,000 lives in 2015. Overdoses kill more people than car accidents, which claimed 37,000 lives that year. Even at the height of the Aids crisis in 1995, 41,000 people were being killed by the disease each year, less than the numbers killed by opioids today. Among the most shocking cases has been Huntington, West Virginia, a city of 50,000 residents, which in August 2016 saw 26 overdoses in less than four hours.

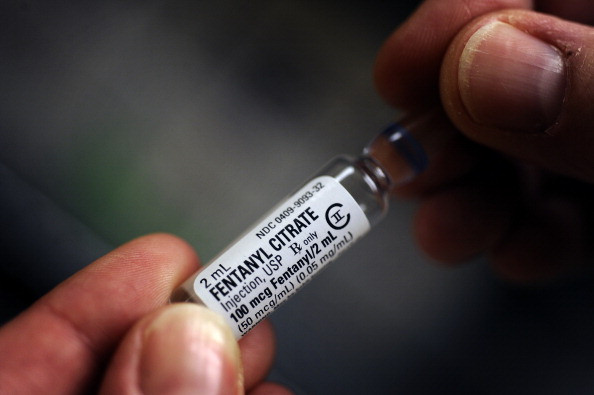

Celebrity deaths have brought the issue into focus too and in April 2016 Prince died of an accidental overdose of Fentanyl, a powerful synthetic heroin that is killing thousands of addicts.

Despite all this, doctors and campaigners say there has been a lack of federal action that they see as shameful.

On Staten Island, one of New York's five boroughs, Richmond County District Attorney Michael McMahon sees the problem in apocalyptic terms. He said: "People are dying in their homes, they are dying in cars, they are dying in restaurants, they are dying in public places. It is happening everywhere. It feels like a horror movie where a segment of the population is engaging in a behaviour that is extremely harmful."

McMahon said that when the Department of Health figures for 2016 are released they are expected to show that last year there were 120 overdoses on Staten Island. Officials are tracking another 90 cases and there were 74 saves by paramedics and police meaning there are around 40 overdoses per 100,000 people, among the highest in America.

According to McMahon, Fentanyl is driving the high death rate because it is 50-200 times stronger than heroin, so toxic that police do not field test illegal substances any more in case they accidentally touch it.

Surprisingly Fentanyl is cheaper to produce meaning that more profit for the manufacturers and a higher profit are making a deadly combination responsible for 50% of overdoses on Staten Island.

McMahon said that he wanted to be "very clear" that the opioid epidemic "is the public safety and public health crisis of the moment in America". He said: "It's certainly an epidemic. I think it's a plague because if people were dying from these numbers from other illnesses we would have people walking around in suits and Staten Island would be quarantined."

Since taking office in 2015 McMahon has been closely working with Luka Nasta, the director of Camelot Counseling, a 45-bed treatment centre on Staten Island.Addicts spend between six months and a year at the residential facility where they take classroom lessons and are given counselling to deal with their issues. Nasta believes that it is the "secret that kills" with drug addiction.

He said: "If we take the secret and we put it on the table and expose we can grapple with it. If it doesn't exist we have nothing to grapple with...the characteristics of addiction are to deny and resist, be it the individual, the immediate family, the extended family, the community, the industry and the government.

"That has enabled it to grow in secret to the point where it can no longer be a secret, it's undeniable, it's categorised as an epidemic. It can't be denied anymore."

Nasta is a former addict himself and survived what he called the "first wave" of heroin that hit Staten Island in the 1970s. As a teen he tried marijuana, hallucinogens and sniffed glue but heroin "crawled up your spine and grabbed you firmly and dictated your next moves," Nasta said.

Asked how many friends he has lost to drugs, he said: "I couldn't even begin to count. I mean I stopped counting, it's too painful to think about."

Among those currently being treated at Camelot is Mike, 30, a former inspector for an oil and gas company, who did not want to give his surname. He got hooked on OxyContin after injuring himself whilst working out at the gym and his doctor put him on 240 of the 30mg pills a month. As his addiction grew, Mike began topping up his prescription and was spending $400 a day on OxyContin pills until a friend suggested he try heroin.

For just $60 he could get a fix that would keep him going for two days. It wasn't much of a choice, Mike admits. Over the next three years his life unravelled; he sold his two cars and moved out of his house and into a $400 a month apartment until he stopped paying the rent. Mike ended up sleeping on a park bench and broke up with his girlfriend.

Soon he began selling firearms and doing home invasions to pay for his addiction. His parents cut him off and he acquired a violent reputation that meant his employer let him go. It ended when his mother had finally had enough.

Mike said: "My mum was thinking I was going to kill myself. She invited me over to get an order of protection against me and called the cops and they took me off. I have no ill will toward her because she saved my life. She's seen me come home covered in blood, she's seen a lot of freaky things that I don't know how she put up with. She saved my life."

Mike has been in Camelot for three months and says this is his last chance. He said: "Part of me feels disgusted for what I've done just to get high. I've ruined relationships, hurt many people including myself. Some people I'm not going to be able to repair those relationships...part of me looks forward to my future and the good life I had before, I could have that again, just don't make the mistakes that I made."

On the face of it, Staten Island seems like the unlikeliest part of New York to have an opioid problem. The borough is heavily Italian-American, blue collar and home to many serving and retired firefighters and police officers. But the large number of people who are insured may count against them as they are able to get ready access to painkillers. Opioid addiction is also a particular problem in the white working class, which is the majority of residents on the island.

The Iaconos fall squarely into that bracket and Anthony Iacono used to be a longshoreman until he fell and hurt his back. His doctor prescribed him OxyContin and over the next five years it "took over his life," his sister Rosemarie said.

Speaking to IBTimes UK from her home in the Bulls Head neighbourhood of Staten Island, she said that her four brothers all supported each other's habits when they were using. They would go "doctor shopping" where each of them would visit multiple doctors in the same day to load up on drugs until that was banned.

In hindsight Rosemarie says that the warning signs were there but she did not realise until too late; strange men would call at the Iacono home asking after her brothers, things went missing from the house as they stole to feed their addiction.

On top of that their mother died when Rosemarie was six so and their father had Parkinson's disease so she became the mother figure of the household. She said: "It was very difficult to live with them, there was always a constant fear. You heard of people overdose. You never think it's going to happen to your family and then one day it does."

Anthony died in 2012 at the age of 29. Raymond died the next year aged 26. Chris, 33, has been sober for five years and Michael, 28, is in recovery.

The blame as to how we got here rests largely with the pharmaceutical industry, according to those spoken to by the IBTimes UK, although law enforcement and city officials have taken too long to face up to the problem as well.

In the 1990s drug companies began to market powerful painkillers designed for serious illnesses for everyday ailments – and downplaying the risks of addiction. The drug industry also convinced the medical profession to make pain a "fifth vital sign" which effectively meant patients and not doctors decided how much medication they needed.

By 2000 doctors were writing 5.9 million OxyContin prescriptions a year which was more than Viagra, according to the Government Accountability Office. As a result, in the 15 years leading up to 2001 the number of overdoses from the drug shot up 400%, according to the Drug Enforcement Administration.

In 2007 Purdue Pharma, the maker of OxyContin, pleaded guilty to misleading the public about the drug's risk of addiction and agreed to pay a fine of $634m. But that did little to stop the glut of painkillers and by 2012 doctors were prescribing enough to give every adult in the US an entire bottle each year.

As of last year OxyContin had earned Purdue $35bn.

McMahon, the Richmond County DA, said: "Seventy to eighty percent of the people who are overdosing now from heroin mixtures started drug addiction on painkillers, either legal or illegal. This continues to be a man made crisis with origins in the corporate greed of big pharma. It's a national scandal that should be examined and uncovered and the people responsible for it should be held accountable. The cost in lives across this country is huge and the cost in dollars is in the hundreds of billions of dollars."

In the absence of federal action individual cities have been forced to come up with their own solutions to the crisis.

On Staten Island that has led to prosecutors aggressively going after suppliers and treating every overdose like any other crime to try and track down dealers, a programme called the Overdose Response Initiative.

City officials and law enforcement are also developing multi-agency programmes to avoid sending addicts to jail. In February they launched HOPE, or Heroin Overdose Prevention and Education Programme, under which cases against addicts will be dropped if they go on a treatment course.

Another way that Staten Island is dealing with the problem is innovative use of data. Rather than relying on Department of Health statistics, which are up to a year old, data is being collected from hospitals and emergency responders in near real time by the Staten Island Performing Provider System, a New York state-funded alliance of clinical and social service providers.

Joseph Conte, the executive director, said that an analysis of 911 calls revealed that 5% of residents make 45% of all ambulance calls. Some people with serious mental and drug issues call for one as much as 40 times a month, and one man calls an ambulance every three days.

From this analysis the group of partner agencies developed a programme called "The Warm Handoff" under which a peer counsellor – often a former addict – is part of the team which treats the individual in the emergency room. The idea is to intervene and break the cycle of addicts repeatedly coming back to hospital to find out what their other needs are and encourage them to quit. The programme launched in November and so far 300 people have been through it, far more than Conte expected.

He has been visited by health officials from Manchester, England, amongst other places, to see how it works. Conte said: "The root analysis of the emergency room figures led us down this path, to look at all these people who make these ambulance calls. It allowed us to peel back the layers...the data doesn't lie."

At Camelot Counseling, Nasta said that other countries should be on their guard as pharmaceutical countries are marketing the same drugs abroad. He said: "I would warn Europe and the rest of the world that there's a devastating epidemic on the horizon and they should learn from the United States' inability to identify it early and deal with it ineffectively. They should learn from our mistakes and prevent it from happening elsewhere."

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.