Isis in Palmyra: Inside Islamic State's war on history in Iraq and Syria

When Islamic State stormed into Palmyra in Syria earlier this year it was feared that the destruction of historic sites at the Babylonian site was only a matter of time. With news that the terrorist group has destroyed the 17AD temple of Baalshamin, that rampage could have begun.

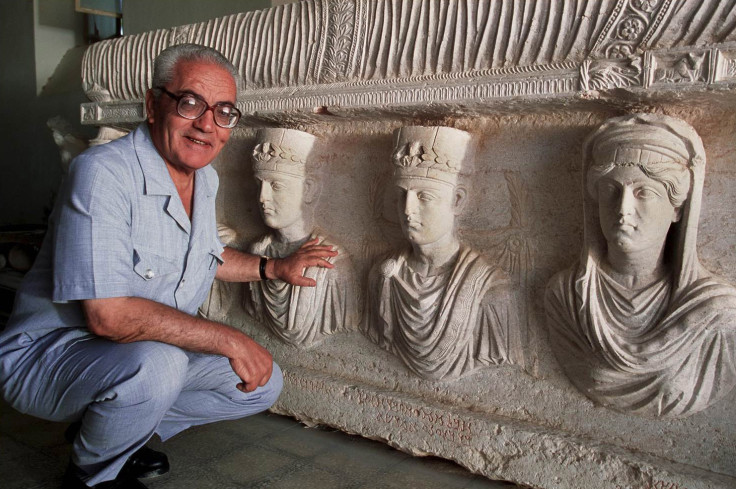

The world recoiled on 19 August at the brutal murder of celebrated Syrian archaeologist and former chief of the ruins Khaled al-Asaad, who was beheaded and whose body was displayed in Palmyra's square after he was accused of being "director of idolaters". Al-Asaad is just the latest of tens of thousands of Syrians and Iraqis – as well as a number of foreigners – murdered by the group during its bloody rule.

'They are very practical about what they destroy. They destroy things that are not easily marketable, and sell the portable antiquities.'

But while IS likes to couch its murders and destruction in the language of extreme religious piety, its true motive is little different than that of militia groups for hundreds of years, namely cash. It has been suggested that al-Asaad was murdered after refusing to direct the group to Palmyra's priceless relics and antiquities, many of which were moved from the site or hidden as it advanced.

In the face of territorial losses in Iraq and in particular the destruction of IS oil facilities and smuggling routes, the group is more reliant than ever on other streams of income and smuggling of historic relics has always been a major cash cow. IS has made millions of dollars either taxing antiquities smugglers inside its territory or directly smuggling artefacts out of Syria and Iraq.

Palmyra has so far escaped the widespread destruction that has been seen in cities such as Mosul and 3,000-year-old Nimrud, which IS dynamited earlier this year and later published a video of the destruction on the internet. Syrian antiquities director Maamoun Abdulkarim said that this was due to Syrian IS fighters' reluctance to destroy what is one of the country's most important sites.

There is also likely to be a financial incentive. Boston University professor Michael Danti, who is academic director at ASOR Cultural Heritage Initiatives, a programme set up by the US State Department, told IBTimes UK earlier this year that militants have been taking clear direction from Sharia court judges to destroy larger idols and sell the rest on the black market. "They are very practical about what they destroy. They destroy things that are not easily marketable, and sell the portable antiquities," Danti said.

IS has likely spent the months since it seized Palmyra sizing up the horde of ancient Roman and Babylonian antiquities that the site and its prominent museum contains. But equally the size of Palmyra and in particular its sculptures do not bode well. Danti said that the group's destruction of Nimrud was likely due to the fact that the 3,000-year-old sculptures were too big to smuggle out of the country – similar to Palmyra.

"Islamic law specialises exactly what to do with antiquities when you find them. You sell them and 20% of the profits goes as a tax. It is right there in Hanbali jurisprudence. They can easily refer to the Koran, Sunna and Hadith and Islamic jurisdiction to tell them exactly what to do. So for a Salafist it is not a difficult dilemma," Danti said.

It has also been claimed that the Syrians among the IS ranks have opposed the destruction of a site that is so important to the country's heritage. As in Cairo in 2011, when anti-government protesters protected the Egyptian museum from looters, there may have been pressure from Syrians to save a site that pre-dates Islam and so could hardly be claimed to be an insult to the religion.

Trail of destruction – The IS war on history in Iraq and Syria

Palmyra

Palmyra has escaped the wholesale destruction that has been seen in some Iraqi cities, but IS has turned its hand to the Muslim shrines on the site. Under the group's extreme interpretation of Sunni Islam, the veneration of early Muslim leaders or their descendants constitutes idol worship and is forbidden.

In June, IS released a video of the destruction of two such shrines in Palmyra. One was the hill-top shrine of Mohammed bin Ali, a descendant of the Prophet Mohammed's cousin, and the other of Abu Behaeddine, a local Muslim leader, both of which were close to the site.

"They consider these Islamic mausoleums to be against their beliefs, and they ban all visits to these sites," Syria's antiquities director Maamoun Abulkarim told AFP.

Abdulkarim told IBTimes UK that IS had also destroyed a 1,900-year-old Lion of Al-Lat statue in front of the national museum. But the jihadist group released a statement on 27 May claiming that it will preserve Palmyra's monuments and the ruins but "pulverise statues that the miscreants used to pray for". It also published photographs online which appeared to show the ancient Palmyra ruins unharmed.

Nimrud

The Iraqi government reported in March that Nimrud, a 13<sup>th century BC Assyrian site, had been bulldozed by IS. Early reports were doubted by some archaeologists, but a video was released in April that showed the ancient city being surrounded by barrels of explosives and then blown up.

Speaking to the camera, an IS fighter said: "Whenever we are able in a piece of land to remove the signs of idolatry and spread monotheism, we will do it. God has honoured us in the state of Islam by removing and destroying everything that was held to be equal to him and worshipped without him."

Nimrud is 30km southeast of the IS-controlled city of Mosul. Originally known as Kalhu, it was built by the Assyrian king Shalmaneser I in the 13th century BC and was a thriving city until 600BC. It was discovered by Western archaeologists in 1820 and damaged during the 2003 US invasion of Iraq. The site is listed on UNESCO's list of world heritage sites.

Hatra

Another ancient city 70km to the south of Mosul, UNESCO revealed that the historic city of Hatra had been blown up and bulldozed in early March. Hatra was built around 200BC by the Seleucid Empire, which controlled the area in the wake of Alexander the Great. Hatra was considered one of the best preserved examples of a Parthian city, according to the Iraqi Cultural Center in Washington.

In a video of the destruction in Iraq, an IS militant compared the action to the smashing of the idols in the Kaba'a by the Prophet Mohammed when he led his army into Mecca from Medina in the sixth century. "We were ordered by our prophet to take down idols and destroy them, and the companions of the prophet did this after this time, when they conquered countries," he said.

Irina Bokova, head of the UN cultural agency Unesco, called the alleged demolition of Hatra "a turning point in the appalling strategy of cultural cleansing under way in Iraq".

Mar Elian Monastery

One of Syria's most renowned Christian sites, Mar Elian was bulldozed this month at Qarytain near the IS stronghold of Raqqa. Mar Elian had been held by forces loyal to Bashar al-Assad until early August, when it was seized by IS and was also the site of the abduction of priest Jacques Mourad in May.

The monastery was founded in 432 on the claimed spot of St. Elian's death and was an important pilgrimage site for the surrounding Christian community. The UK-based Syrian Observatory for Human Rights (SOHR) reported that IS also abducted 230 Syrian Orthodox Christians and Syrian Catholics when it seized Qaryatain. Of those captured, 48 have been released and 110 were transferred to Raqqa.

Emma Loosley, the former custodian of Mar Elian, told IBTimes UK that Mar Elian had been a shrine for Muslims as well as for Christians for 1,500 years. "The Muslims of Qaratayin revered Saint Julian the same way as Christians did and they are going to be just as devastated as them about this. That shows that IS are not real Muslims. If they were true Muslims they wouldn't be doing this," she said.

Mosul Museum

In one of its first broadcasts relating to the destruction of historical sites, Islamic State issued a video in February that showed fighters smashing 3,000 year old statues at Mosul museum with hammers as well as using drills to destroy every statue in the museum, including a winged-bull Assyrian protective deity dating back to the 7th century BC.

"These ruins that are behind me, they are idols and statues that people in the past used to worship instead of Allah," an IS militant tells the camera. "The so-called Assyrians and Akkadians and others looked to gods for war, agriculture and rain to whom they offered sacrifices," he added, with reference to the ancient civilizations that lived in Mesopotamia for more than 5,000 years in what is now Iraq, eastern Syria and southern Turkey.

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.