Isolated LGBTI Ugandans face traumatic persecution in Kenyan refugee camps

Despite the omnipresent dust, Charles Iwara's toe polish still stands out as she sits crossed-leg on her makeshift bed. She tries to hide her pain behind a smile but her eyes tell another story.

A transgender person who identifies as female, Charles, fled Uganda's anti-gay laws, attacks, and witch-hunts in January 2015 thinking she would get protection. However, like many members of Uganda's lesbian, gay, bisexual, trans, and/or intersex (LGBTI) community she now faces a life of suffering after having sought refuge in Kenya.

The December 2013 passage of the Anti-Homosexuality Act opened the floodgates for systematic human rights violations against LGBTI people in Uganda. Newspapers outed alleged homosexuals by publishing their pictures, and leaders and media publications called for the execution of gays. This prompted scores to flee the country.

Around 100 LGBTI people have ended up in Kenya's second largest camp, Kakuma. Because of rampant hostility toward lesbians and gay men, the United Nations' (UN) refugee agency that runs the camp was forced to accommodate them in four so-called "protection areas".

While Charles found somewhere where she was accepted by fellow LGBTI people, walking outside of his compound could mean sexual violence, beatings and even death.

"I thought I would get help but it's been a year and a half now, and I have had no help. I can't hide I'm gay because I'm a transgender. When I leave the compound, people start beating me. When I've told officers, they told me 'Go and stay in your compound'. That means I can't get food other than the ration. But rations aren't enough," Charles told IBTimes UK in her makeshift bedroom.

'Beaten by police' in their home

Listening to refugees' stories, it is easy to see the real issue comes from a lack of protection. One of Charles' friends [who we will call David] explained how the little group fears attacks from both other communities within the camp, and lamentably, alleged attacks from the police and the Turkana host community. Indeed, he said, in December last year, police officers raided the little compound after accusing the group of 'unlawful gathering'.

"Last year, the police in charge of security in the camp [General Service Unit (GSU), a paramilitary wing of the National Police Service of Kenya] themselves attacked us. Inside this very community, people were beaten, then imprisoned for no good reason. As they were beating us, officers told us we were not allowed in Kenya. If police themselves can beat us, what about other people? So that's our life here."

David added: "I got the idea of running away and went to UNHCR in Kakuma for safety and protection. We're not the first LGBTI in Kakuma, and UNHCR knows what those who came first experienced. However, still in the protected area, people have suffered a lot here. I fear at times it's worse in the protection area – as if there is no protection. In a protection area, the first organ you need is police, but police is not on your side and don't like us."

The beleaguered LGBTI explained they are easily identifiable as such because, contrary to other refugees, they arrive at the camp speaking fluent English but little Swahili. "So if we go there and can't speak Swahili, and can't speak any other language apart from English and our mother tongue, then they know we are Ugandans and 'suggas' (a pejorative term for homosexuals). We can't change the way we speak and cannot hide who we are," David explained. The young man highlighted that individuals are solely opting to be refugees from Uganda in 2016 due to the draconian Anti-Homosexuality Act.

Socially conservative Kenya is one of 78 countries worldwide that have laws banning sexual relations between consenting adults of the same sex, yet, for these refugees, there is nowhere else to go. In May, rights groups urged the government to take immediate steps to ban forced anal examinations of men accused of homosexuality.

Asked to comment about these claims, one of UN's refugee agency heads of sub-office in Kakuma said the UNHCR is aware that police went to the compound and allegedly beat the refugees.

"We specifically told police they cannot beat people," the UN worker, who cannot be named, told IBTimes UK. "I told police that, when it is working with any refugee group, they need to abide by human rights laws. We can't ask for police officers' removal, but within the UNHCR (camp), police cannot break laws, otherwise they face losing their jobs."

In 2015, the group explained how homophobes in Kakuma went an extra mile by pinning posters across the dusty sprawling camp, warning they would be attacked. "We reported it to the UNHCR which told us: 'Protect your souls'. Nothing was done." While refugees understood the UN had little power when it came to investigating alleged police wrongdoings, David said: "Putting us here (in the protection area) is the only thing they can do as UNHCR. If the police won't protect us, UNHCR can't protect us."

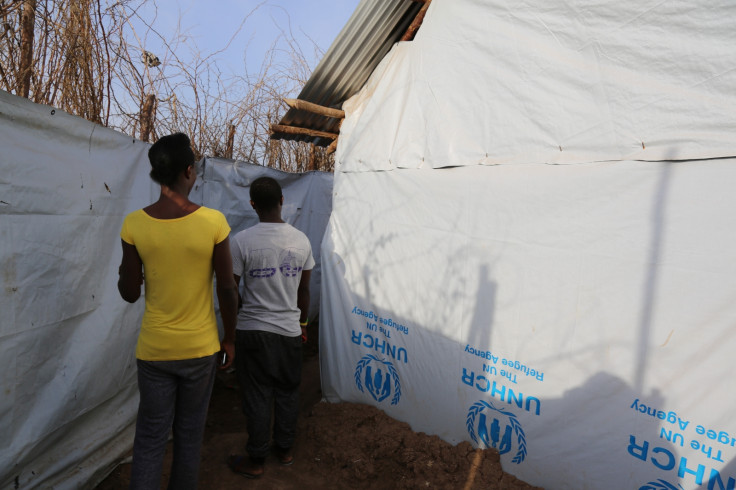

As they show IBTimes UK around their compound, Charles and David point out the flimsy, thorny hedge that protects the tin roofed and plastic sheeted houses from outsiders' attacks. Looking at the large expanse of field behind the hedge, Charles said she was once attacked by members of the host community who allegedly came up to the fence and threw rocks at her. At night, the 25-year-old said, two or three members of the LGBTI community stay up to guard their area.

Failing to access basic services for refugees

Due to their lack of mobility outside of their encampment, the group described how it was failing to access basic services provided to other refugees - including food provision, healthcare and education.

After hearing others' stories, another young transgender person [who we will call Betty] told IBTimes UK how she was raped by another refugee a month ago. Too fearful of attacks, and unable to leave her room, Betty explained that she did not report the assault and did not go to the humanitarian agencies to access anti-retroviral (ARV) medication to prevent HIV-infection.

"I don't know if I have caught it. But I cannot leave, so I will remain without knowing. I cannot speak to anyone about it. I feel so sad. I would like it if a counsellor could come to meet me," Betty said.

While the UNHCR decided to bring food rations near the protection area, Charles said the group still faces trouble because it has to go and collect the food, as they are mixed up with different nationalities from other protection areas. If they do venture out as a group to buy items from the grocery store, the refugees are also sent away by the shop owners.

David explained how, after having applied for a job as a teacher within one of the camp's secondary schools, students living in a neighbouring community had recognised his identity. "When I turned around at the blackboard to write something, the students would say 'suggah'. In the staffroom, when other teachers found out I was gay, if I touched something they would never touch it. When I asked for help, they never helped me. I was so discriminated, I felt so depressed I ended up quitting my job. So now I'm jobless."

Most in the group are religious but they claimed the camp churches they started attending upon arrival "were preaching against homosexuality". "The churches we used to go to rejected us, when they realised we were LGBTI. So we decided to found our own church (in one of the compound's dwellings) and that's where we go for our prayers on Sundays. Everyone from the compound goes. We don't go outside for prayers."

Facing shocking 'corrective rapes'

Two young women, both in their twenties, opened up about a shocking practice they reportedly face each time they walk past the compound's gate: so-called corrective or curative rapes, a hate crime wielded to convert lesbians to heterosexuality through rape.

"The men threaten us all the time," Sarah said. "When you are coming back from the grocery store, men say they will rape me, they follow me. So when I have to go to the town centre, friends come with me, but most of the time we have to stay inside."

This was echoed by Mary, who told IBTimes UK how, following their arrest in December last year, the girls were jailed in Lodwar, a town within a two-hour drive from Kakuma. "When we were imprisoned in Lodwar, those guys used to come and say: "You claim to be LGBTI but here in Kenya we don't allow LGBTI women so you must sleep with us, and you are going to change by force. If not, we are going to deport you back to Uganda"," the young woman recalled.

"So, every night they were coming to threaten us, beating us in our cells. Some of us stayed in the cells for three days, other stayed for more than three months."

Arbitrary arrests and 'trumped up charges'

While many refugees in the LGBTI community claim to have been arbitrarily arrested and say they would like to be resettled, Charles is facing an uncertain future. She was arrested following an incident where she was accused of beating another refugee and is now facing trial.

She explained: "15 of us were going to the shop to buy some food and airtime. People started calling us 'Suggah' and started beating us. We tried to seek help, police came and took us to the police station. A refugee told them I had beaten him, and he opened a case. I spent one week in prison."

Requirements for settlement include having a clean criminal record. In the UK, for instance, a refugee can only be considered for resettlement if two years have passed since he, or she, received a sentence.

Charles continued: "When I was released I tried to tell the UN it was not true, but they could not do anything, as my case was now in the hands of the government. I didn't come here to cause problems or be charged. I cry and tell myself I want to die because there is nothing I can do. I have no hope of getting resettled as no process can be started if my case is still pending."

This sense of helplessness and lack of access to counselling has, sadly, pushed some to try and take their lives.

"We are only counselled here by people in our own house, but almost everyone has gone the extra mile and feel that life is useless. Let me die," Patrick, one of the community's men, told IBTimes UK. Another, who we will call Joe, added: "We would like counselling services to be extended to our community, because many of us are really tortured and we just need someone to talk to. Things are still haunting you and you don't have anyone to talk to (...) At times, we want the UN to have guns and come and shoot us, so we could die instead of suffering here."

The UN officer, meanwhile, said the agency was "trying to assist them and protect them" but that the group "also has to cooperate with us". She told IBTimes UK she was hoping to set up a meeting with police officials, LGBTI members and representatives of the UNHCR to find solutions to the issue. IBTimes UK was unable to reach Kakuma police for comment.

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.