'I've never said that I don't believe in God' says 'blasphemous' Algerian writer Anouar Rahmani

IBTimes UK exclusively speaks to novelist Rahmani about his struggle for freedom of expression.

"I want to tell them that my dream is to live in a place where every religion, every sexuality or sex is accepted as equal. Now, we have a big country, but we feel it is an open jail, without freedoms. This is not what Algeria deserves to be. I want to see my country one day as big as its own map."

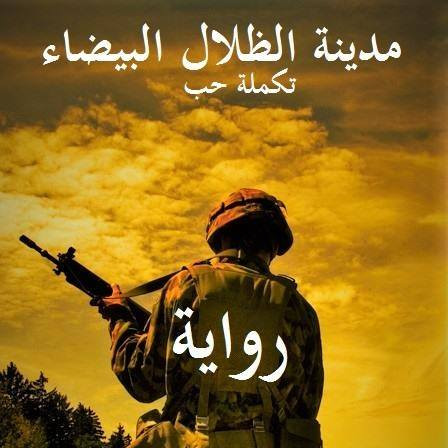

These are the words of Anouar Rahmani, a young writer, who is waiting to hear whether he will be charged in a criminal blasphemy investigation over his 2016 novel The City of White Shadows, which depicts a gay romance between an Algerian freedom fighter and a French settler during the war for independence.

But while homosexuality is still illegal in Algeria, the fictional plot is not what drove most questions the police asked Rahmani when they interrogated him. They wanted to know why he had written a chapter in which a child converses with a homeless and delirious man who calls himself "Allah" (God).

For this chapter, the 25-year-old, who has been an LGBT and minorities advocate for years on his blog, is under investigation pursuant to Article 144bis of the Penal Code, which provides for a prison term of three to five years and a fine of up to 100,000 dinars ($914, £752) for "offending the Prophet" and "denigrating the dogma or precepts of Islam".

"I have never said that I don't believe in God, I just said that you have to respect other people – being different is not a crime. I have never made a coming out about myself, for instance, I have never said that I am gay, bisexual or anything," Rahmani, who studies law and lives in the seaport town of Cherchell, tells IBTimes UK.

Speaking from his home, which he shares with his family, the young man explains that because of his liberal thinking in a Muslim country, which he says is slowly become more conservative, Rahmani has been the victim of daily attacks on social media platforms and in local broadsheets. "It's not the first time, I've lived with these bad comments for years on Facebook and in newspapers, because of my blog, my writing."

But critics' attention is affecting his parents. "What I care about more now is my family's situation. In my eyes, I kind of deserve (the situation in which I am), in a sense, because I just wrote something that authorities could not have liked, but I am really feeling there is a big pressure on my mother and father, who are so scared now. It's a psychological pressure," he says.

His traditional parents are not used "to having a famous son". "They are old and are feeling scared of this. My mother becomes agitated when she hears me speak on the phone, asks me not to talk. She thinks that by speaking I will be more in danger. I can see this in my parents' eyes. But they are not responsible for what I am doing, and I fear they will face the same stigma society has imposed on me."

'I can go through this, I am not afraid'

For the moment, Rahmani is free, pending a decision by the prosecutor on whether to officially charge him, after police sent its report of the prosecutor's office. Having spoken to lawyers, Rahmani says he expects the procedure could take weeks, or maybe months.

"I am not afraid of the justice because it's an honour for me that I may be going to court for something that I wrote, not for someone I killed for instance – I am a writer and not a criminal. I am proud of this," he says, in an upbeat tone, before adding: "Even though it is not just to take someone to jail for something he wrote out of his imagination, I can go through this, I am not afraid."

The young man still attends university, but says it is becoming increasingly difficult to carry on his life as usual. "Somehow I manage to keep on doing some daily activities, but when I went to university yesterday (9 March), they were all looking at me, I didn't feel comfortable. Someone even came to me and asked me I believed in God, and if not what did I believe in?"

It is precisely these questions that the young man has been forced to answer for months now, and which have led critics to accuse him of blasphemy and apostasy, and being an LGBT rights activist.

"I have never said that I don't believe in God, I just said that you have to respect other people – being different is not a crime. I have never made a coming out about myself, for instance, I have never said that I am gay, bisexual or anything. Sexuality is something personal to me, but what I wrote is what I believe about the struggles people face. Yesterday, the students were looking at me in a bad way. Even those who want to be around me can not because they are afraid the same thing will happen to them. They keep themselves away."

Does Rahmani understand why people his age, who grew up in the same town and probably listened to the same music or read the same books as him, would be so critical of his ideas and writing?

"The majority are not necessarily smart – in every sense of the word. They are now allowed to express their own opinion on things, and repeat what they are told to say from a young age. They may use their mouths and tongues to talk, but they are not using their own judgement to formulate sentences," he says.

Authorities are 'making Algeria the second Afghanistan'

Following a brutal civil war in the 1990s, which killed up to 200,000 people, and the Arab Spring in neighbouring Tunisia and Libya, authorities in Algeria – the biggest country in Africa – heavily invested in its youth, pumping money in interest-free loans or building new homes, for instance. But many youths like Rahmani say they find it hard to escape the claws of the more conservative elders, including the government.

"I cannot blame young people, but I blame the university, the media, the state and the judicial system for making Algeria the second Afghanistan. I don't understand why I can be Algerian, living in a country with a long history of ideas of revolution and freedom but regressing now. People who are governing Algerian want this: they are making Algerians think that way so they can control them."

He adds: "My purpose in this life is not to insult God, or religion. My dream was always to be a writer, and this is what I am – doing what I was born to do. I want to tell them that my dream is to live in a place where every religion, every sexuality or sex is accepted as equal. Now, we have a big country, but we see it is an open jail, without freedoms. This is not what Algeria deserves to be. I want to see my country one day as big as its own map."

Advocacy organisation Human Rights Watch has urged the Algerian authorities to uphold freedom of expression and take immediate steps to abolish the blasphemy law.

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.