Jamaica's killer cops: How the families of police victims face intimidation and violence

In 2015, 8% of all murders committed across Jamaica were at the hands of law enforcement officials.

The strength of the sun shining down on the colourful Orange Street in downtown Kingston announces that lunchtime is approaching. A group of young men chat on the pavement while reggae music floats out of a small radio in a corner.

Three women catch up on the morning's events in a small but busy hair salon. Next to them, a young man vigorously cleans a stove ahead of the lunch rush.

Daquan Jakson, 19, is in charge of a small restaurant that prepares lunch for many who live and work in this bustling quarter of Jamaica's capital.

Daquan is not a cook, or at least he wasn't until a few months ago. But then tragedy struck his family like a deadly thunderstorm, and the youngest of seven siblings decided to take over the business.

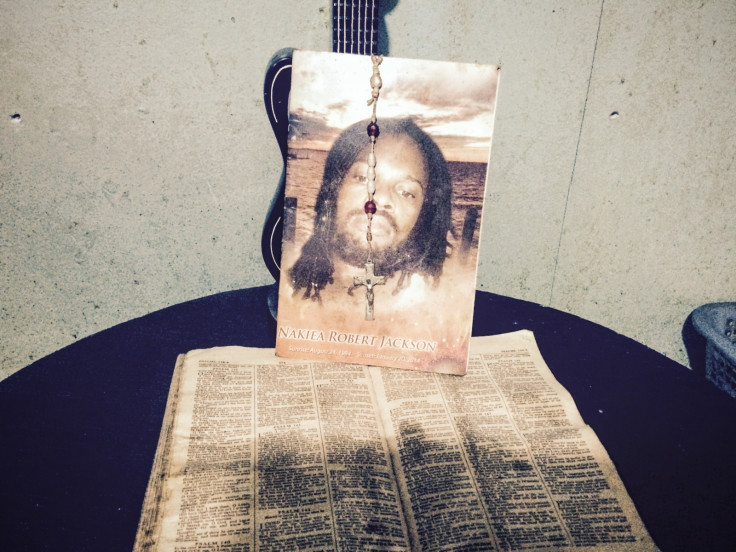

The picture of a smiling young man hanging on the small room's yellow wall hints at the story that has defined their lives for the past three years.

Killer cops

Daquan's brother, Nakiea, then 29, was known around the neighbourhood for his cooking skills. On the morning of 20 January 2014, he was busy cooking a large lunch order of fried chicken for the local branch of the National Blood Bank when, according to eyewitnesses, a police officer stormed into his shop and shot him.

The young man was thrown in the back of a police car and taken to hospital, where he died from two gunshot wounds, according to an autopsy. Nakiea had been unarmed at the time of the shooting according to witnesses. The police officers had been looking for an alleged crime suspect – a man with dreadlocks. Nakiea fit that description.

One of his sisters, Shackelia, remembers the day as if the clocks had stopped the moment she woke up to shouts of her brother's name.

"I rushed into the room and saw all the food being prepared, like any other day, and then I noticed one of his slippers on the floor ... and water dragging blood marks. My heart stopped. My life stopped that day," she said, standing on the very spot where her brother had been shot three years ago.

Shackeila locked the cook shop and, almost instinctively, she preserved the crime scene.

Her instincts were right.

Jamaica has one of the highest crime rates in the Americas. With 43 murders per 100,000 inhabitants recorded in 2015 alone – only behind Honduras, El Salvador and Venezuela.

Over the past two decades, Jamaican authorities have sought to fight the country's crime rate with a tough approach which has resulted in more than 3,000 killings by the police since 2000. In 2015, 8% of all murders committed across Jamaica were at the hands of law enforcement officials.

The Jamaican authorities claim they are taking steps to tackle this crisis. But, despite a steep reduction in cases of killings by the police over the last three years, most of the cases have not yet reached the courts and remain in impunity. Despite overwhelming evidence of police involvement in the crimes, only a handful of officers have been convicted of murder in the last two decades.

If justice is not done, how can we convince our children not to hate the police?

But it gets worse. As a new Amnesty International report explained, the numbers only tell half of the story. Some Jamaican police harass and intimidate relatives of those killed to prevent them from seeking justice, and often terrifying them into silence.

After Nakiea's killing, his family have fought relentlessly in the courts to ensure those suspected of the crime face justice. But instead of securing a day in front of a judge, the police have targeted them with a campaign of harassment, intimidation and violence.

Living in terror

In dozens of cases, Amnesty International's research revealed how police employ illegal tactics to instil fear and prevent justice from taking its course. Police officers have raided relatives' homes to stop them from showing up at court hearings, harassed witnesses to prevent them from testifying and intimidated those who managed to be heard inside the court room.

In some cases, police officers have even appeared at the victims' funerals, in a bid aimed at intimidating the surviving relatives and deterring them from pursuing justice.

"We are scared of the police, of their very presence. This violence is affecting a lot of children in the communities. If justice does not prevail, we all become targets, we are all in danger. If justice is not done, how can we convince our children not to hate the police?" said Shackelia.

"This fight for justice has taken over my life. I had to quit my studies, cover all the expenses we had to face over the last three years. I see my father die slowly every day, because of the raids, the harassment, the lack of action," Shackelia explains, her eyes watering out of pure frustration.

Case dismissed

In a shocking but unsurprising turn of events, the case against the police officer who shot Nakiea was dismissed in July 2016 after one of the key witnesses refused to appear in court, too afraid of what could happen afterwards. The family is appealing the decision and remains determined to see justice delivered.

"The problem in Jamaica is the system. The system is broken. While I know the shooter is responsible for my brother's death, it is the system that has allowed this to happen in this and so many other cases," Shackelia said.

"We should at least have the opportunity to go to trial, to have a jury hear the case. I want to have the opportunity to see all the evidence and defend my case. I only want justice. This is not an equal fight, but I'm too much of an optimist and will continue in my fight for what is right."

Josefina Salomón is a researcher at Amnesty International.

© Copyright IBTimes 2024. All rights reserved.