Japan's Emperor Akihito has hinted he's too old to rule – shouldn't Queen Elizabeth do the same?

Can a modern democracy function with a centenarian head of state?

The Queen remains so adamantly against abdication that, according to one courtier, just mentioning the A-word in her presence is "like saying the F-word in church."

Given the lasting trauma of the 1936 abdication and her 21<sup>st birthday vow that she will serve for her entire life, the sovereign – health permitting – is set to reign until well into her nineties and could even mark up a ton like her mother.

But the last half-decade has seen the 75-year-old Queen Beatrix of the Netherlands, the 79-year-old King Albert II of Belgium and the 76-year-old King Juan Carlos I of Spain all abdicate, with Pope Benedict XVI also stepping down at the age of 85.

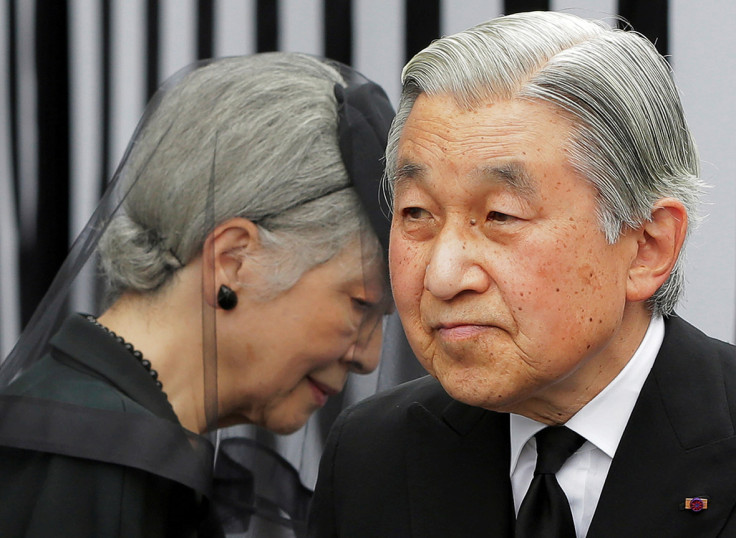

In a televised address on Monday (8 August), Japan's 82-year-old Emperor Akihito dropped a strong hint that he wishes to hand over the reins to someone younger, shouldn't Britain's 90-year-old Queen also consider her position?

Many feared for her health at last November's Remembrance Day ceremony at the Cenotaph when party leaders failed to agree on a plan to shorten the service. They each wanted their wreath-laying moment in the sun – or rather in the cold.

But was it right that an 89-year-old woman should have to stand outside for half an hour on a chilly winter morning? Should Charles have taken her place as he is now obliged to do at many investitures and Commonwealth Heads of Government Conferences? Indeed will there come a time soon – after the daily grind of working through all the official papers in the red box proves too great – when he will have to do it more formally as regent?

With abdication ruled out, the sovereign might take a leaf out of Emperor Akihito's book and make plans for a regency triggered by incapacity. Alas, the only precedent is not propitious: the Prince Regent ruled in a louche and self-aggrandising manner between 1811-20 before George III – mad, blind and deaf – eventually died.

Charles III would probably be loath to accept retirement so early in his reign, but the next generation of royals might be more amenable to radical reform.

The future George IV was much lampooned for his unseemly hankering for the power (particularly after an attempt at a regency in 1788-9 came to nought) but today the transition would be more clearly regulated under the 1937 Regency Act which spells out how and when the heir apparent can replace an incapacitated sovereign. The task of deciding that the monarch is "by reason of infirmity of mind or body incapable for the time being of performing the royal functions" lies in the hands of the Lord Chancellor, the Speaker of the Commons, the Lord Chief Justice, the Master of the Rolls and – somewhat less democratically – the sovereign's next of kin.

Some constitutional traditionalists like Vernon Bogdanor have argued that the regency legislation provides an adequate safety net in the extreme case that the Queen is no longer able to perform her functions. To go any further would be alien to our constitution since, in his view "the concept of retirement is unknown to the British monarchy." If abdication were a ready option, then it might encourage Prime Ministers to pressure a troublesome monarch to resign.

But do the changed demographics of the House of Windsor with the Queen now 90, her husband 95 and her mother living to 101 necessitate a more radical rethink?

With royals demonstrably living much longer and Charles unlikely to reign until well into his seventies, the monarchy will have to address the deepening actuarial problem of an extended run of ageing sovereigns (not to mention the concurrent log jam of multi-generational heirs to the throne).

The 88-year-old King Bhumibol is still going strong in military-ruled Thailand and the 92-year-old President Mugabe may be determined to soldier on in his autocratic Zimbabwean fiefdom, but can a modern democracy function with a centenarian head of state? Even the eternally popular Italian President Carlo Ciampi decided a few years back that he would not serve another term when he reached 85.

One solution might be to impose a cut-off point at around eighty when rather than abdicate, the sovereign could delegate core constitutional duties – including giving royal assent to legislation, appointing prime ministers and nominating or dismissing governors-general – to a regent. It is obviously too late for this to happen under Elizabeth II and after waiting so long for the job, Charles III would probably be loath to accept retirement so early in his reign, but the next generation of royals might be more amenable to radical reform – particularly Prince William who may have to endure another 20 years of criticism that he is work-shy before he actually gets the top job.

If there were a clearer age limit then heirs to the throne could plan their work trajectory with greater certainty and in the case of William, perhaps pursue a more structured career in, say, the armed forces or the Ministry of Defence as an administrator or even the Foreign Office as a governor or roving ambassador.

All these professions are notable for having a mandatory retirement age well before 70. So, isn't it time we recognised that a nonagenarian head of state is a nonsense?

David McClure is author of "Royal Legacy" at Thistle Publishing 2015.

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.