John McAfee: An email hack can destroy our digital world and we won't see it coming

When the personal information of 20,000 FBI employees and 9,000 Department of Homeland Security employees was hacked and dumped online in a Dark Web file on Monday (8 February), the following words were attached:

"Long Live Palestine, Long Live Gaza: This is for Palestine, Ramallah, West Bank, Gaza, This is for the child that is searching for an answer."

The alleged hacker, who goes by the Twitter handle of @dotgovs, said that he or she had downloaded 200GB of sensitive information from the Department of Justice. If true, then the data obtained is 1,000 times deeper than the 30,000 records released. The hacker claimed to have compromised US Department of Justice (DOJ) email accounts and gained access to its intranet.

How credible is this claim?

In a test carried out by Intel, 97% of computer users failed to identify all 10 out of 10 phishing emails as being illegitimate. A hacker sending multiple types of phishing emails could confidently expect that the vast majority of recipients would provide the hacker with their passwords.

A ZDNET study found that with a single phishing email, an average of 45% of users submitted their full login credentials.

Email lists are available from nearly every government agency and corporate entity. There are 123,000 DOJ employees: if the average holds true, a single phishing scheme would collect the login details of 55,500 of them. These employees would span the lists from finance to operations to secret surveillance programs. The logins would give the hacker access to DOJ intranets and, from there, access to everything that the compromised employees had access to. A 12-year-old child could have done this. No exaggeration. Literally, a 12-year-old.

There are phishing templates all over the internet. All the child needs to be able to do is access email lists (all over the net), know how to send an email, and collect the results with the help of a few friends.

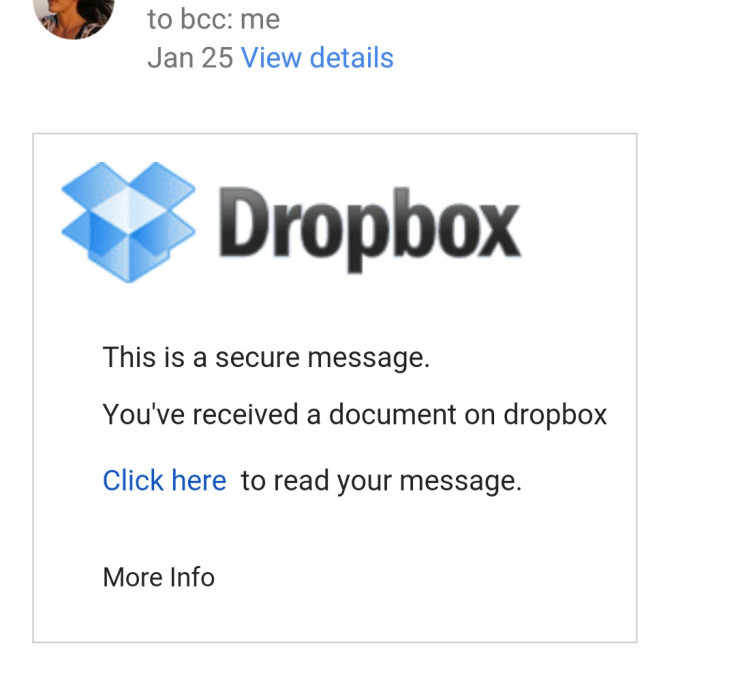

I receive phishing emails many times a day. I hope I am adept enough to identify them. However, I nearly get snagged from time to time. I received one last month that nearly caught me. It looked like this:

The link sent me to a page that had the name of someone I had not heard from in quite a while. It said simply "Have you forgotten me?" There was a link for me to log into Dropbox to get the full message for which I would have to sign in to Dropbox using my email. I did not because no one had ever before sent me a message via Dropbox, and I was suspicious. Later that day I received a bulk mail from the person in question saying her email had been hacked.

Smartphones tell the world everything about us

Now, how did the email know that I had not been in contact with this person for quite a while? Simple. Our smartphones and the huge volume of applications that we download tell the entire world everything about us.

Twenty percent of all apps ask for permission to access our contacts, and a further 10% ask permission to read our emails and text messages. Nearly all want access to our location and our wi-fi connection. Five percent want to make phone calls on our phones, without notifying us, that we sometimes must pay for.

Another 5% ask permission to send emails and text messages on our behalf without notifying us. A full 15% ask permission to take photos or videos or to record conversations without notifying us. All of these apps sell on or give whatever information we allow them to third parties which are always unnamed.

Everyone should know the above because I and hundreds of others have been screaming it from the rooftops for years. But it takes many poundings of a hammer to finally set a nail.

So, the hacker who sent the phishing email I received had access to every contact and every email sent by my estranged acquaintance. It would take the most trivial of scripts to identify those people who had not been in touch for a long time, but this simple piece of information added tremendously to the credibility of the scam. Had we been in touch recently, the email would simply have said "please read this about yesterday's emails" or similar.

How an email hack can cause chaos

We seldom consider the wide-ranging implications of someone hacking into our accounts. Assuming they don't change our passwords and lock us out – the worst-case scenario – we are still in a world of hurt. Every email that we send or have sent and received can be read by the hacker.

Every social media account or private website that we use can be accessed by the hacker and all of our private messages can be read. Bank and credit card statements, online purchases, credit reports and every other kind of financial information can be accessed. And of course, our contacts, which the hackers then uses to propagate additional phishing scams.

But what happens if the hackers lock us out of our social media and other private website accounts?

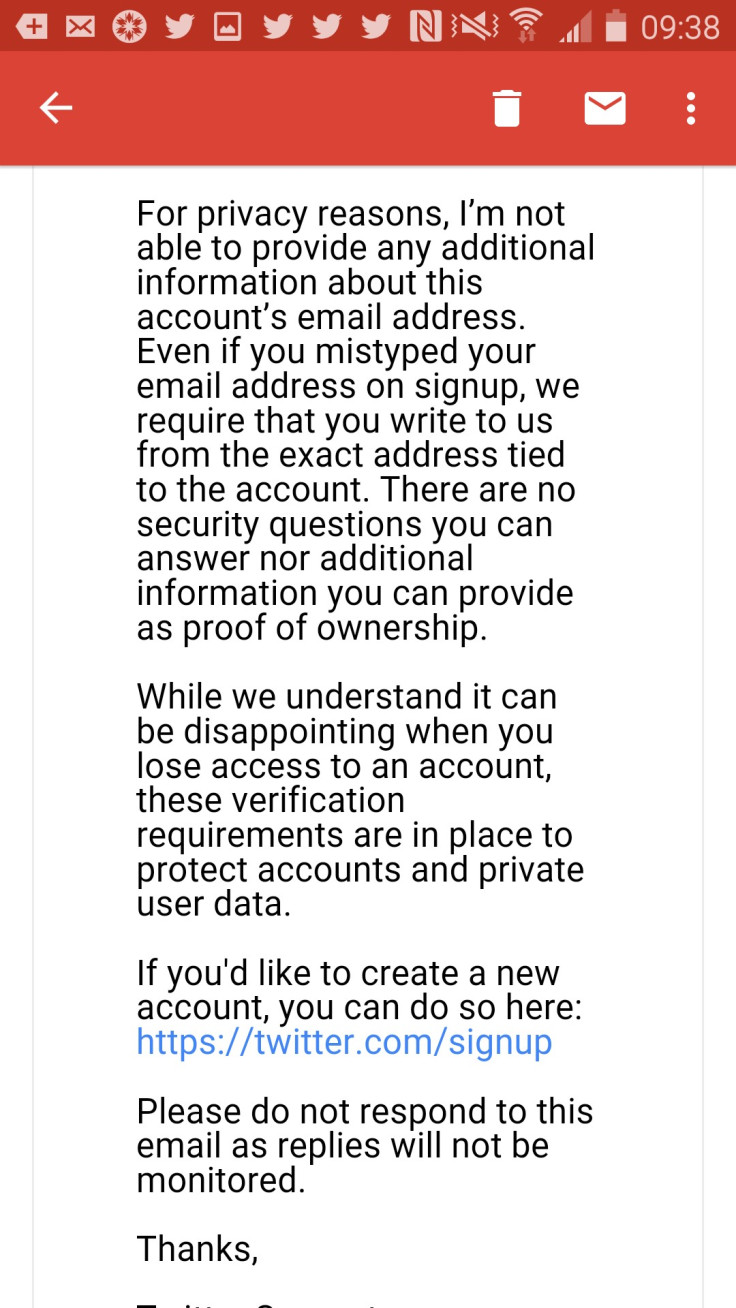

This happened to me for a short period when one of my fired campaign workers locked me out of Twitter, which the worker was managing. She also changed the password and credentials for the email account used to log on to Twitter.

I sent numerous emails to Twitter security and, after many back-and-forths, received this communication:

The authorities finally got my Twitter account back but not before the fired worker had sent out dozens of bogus tweets pretending to be me.

My point is this: email accounts are the fundamental identifying elements of the internet. The assumption is that if a person has access to an email account then that is the real person. Yet these accounts are the easiest elements of the digital world to hack into. It has been estimated by various hacking groups that the passwords for more than 75% of all the world's email accounts are available for purchase on the Dark Web.

If this paradigm does not change, and soon, there will be no private information left in the world.

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.