Labour's election manifestos: From 'new politics' to the 'longest suicide note in history'

You can't judge a book by its cover, so the saying goes. But what about a general election manifesto? Well, that's a different matter.

Every aspect of a party's campaign is carefully managed today as researchers, coordinators and "experts" agonise over the finer details.

How many opinions changed, warped and constructed Labour's 2015 general election manifesto cover is anyone guess. Whatever the answer, Ed Miliband will be launching the policy document in Manchester later today. It certainly looks different to Labour's 2010 Soviet art style offering.

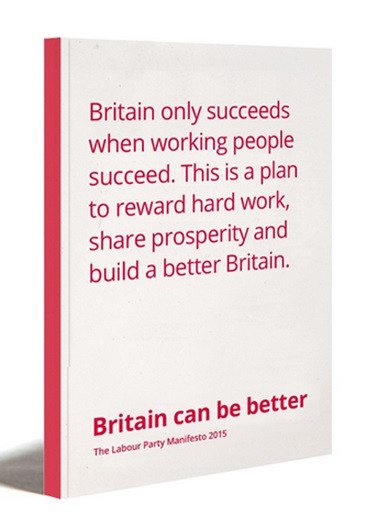

The manifesto argues "Britain can be better" and attempts to paint Labour as the fiscally responsible party, by promising that all of the policies will be fully funded and require no extra funding.

This commitment is no accident – Labour do better on the NHS than the economy in the opinion polls, but now they're hoping to secure more credibility from the electorate.

Before voters can read this message, they are confronted with a bold, red message on a white background: "Britain only succeeds when working people succeed. This is a plan to reward hard work, share prosperity and build a better Britain".

A 22-word slogan, hardly short, is a continuation of Labour's "cost of living crisis" attack. Miliband, however, is absent.

The Conservatives have been goading for a straight one-on-one comparison between David Cameron and the Labour leader, suggesting that voters will pick the Prime Minister over the challenger.

The manifesto cover shows Labour aren't going to take the bait, unlike their historic 1997 cover, their main man won't feature on the front.

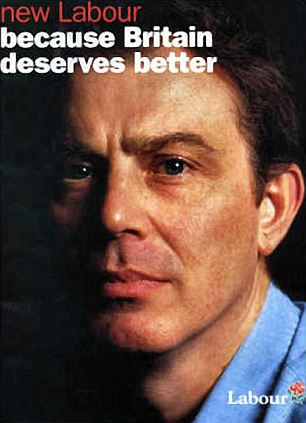

1997 – A New Politics

Labour's 1997 election campaign was a slick, almost mechanical operation. The left-wing party finished its journey into the centre ground on the back of Neil Kinnock's modernisation programme. But the Welshman failed on one important aspect, the press.

Peter Mandelson and Alistair Campbell made sure New Labour, with its "new politics", wouldn't make that mistake. The operators wooed the national media, winning the support of the most popular paper in Britain, The Sun.

At centre stage was Blair, a former barrister and competent media performer. He was up against John Major, a slow talking, grey haired and bespeckled Prime Minister.

Blair, a fresh face, offered a big contrast to the headmaster-esque Conservative and Labour's 1997 manifesto reflected this change. It was all about "out with the old, in with the new".

"The reason for having created new Labour is to meet the challenges of a different world. The millennium symbolises a new era opening up for Britain.

"I am confident about our future prosperity, even optimistic, if we have the courage to change and use it to build a better Britain," the forward read.

"To accomplish this means more than just a change of government. Our aim is no less than to set British political life on a new course for the future."

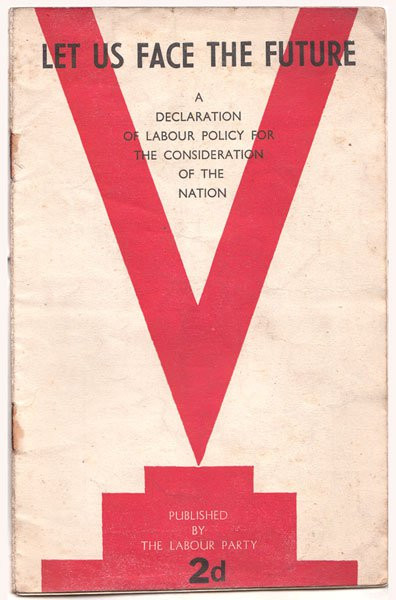

1945 – Let us face the future

But with change comes criticism and some on the left, dubbed Old Labour, opposed the shift to the right.

For them, New Labour had moved too far from its roots – away from democratic socialism and towards Clintonism.

A betrayal, in their eyes, of the beatified Labour Prime Minister Clement Attlee and his vision for Britain.

Labour's 1945 election manifesto cover was adorned with a large red "V", perhaps invoking victory and vision. The post-Second World War policy document argued that a political and economic elite, the so called "hard-faced men", controlled the government, the banks, the mines and the press.

"They had and they felt no responsibility to the nation," the manifesto stated.

Labour, on the other hand, spelled out their plan for a welfare state, full employment and a National Health Service on the back of the 1942 Beveridge Report on "Social Insurance and Allied Services".

The radical policy package won over the electorate and saw Attlee kick Tory war hero Sir Winston Churchill out office.

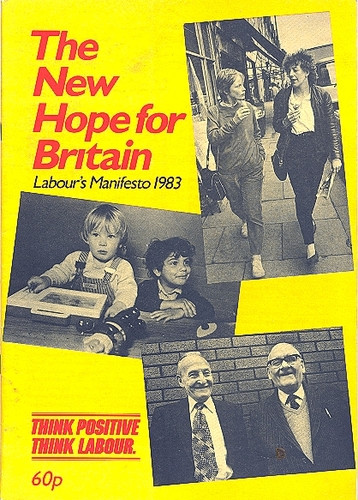

1983 – The new hope for Britain

Labour's 1983 election manifesto and its cover, however, is one that the party wants to forget.

Sir Gerald Kaufman, then a member of Michael Foot's shadow government, famously dubbed it "the longest suicide note in history" after Margaret Thatcher thrashed Foot in the polls.

Labour lost 60 seats in the House of Commons and the party's share of the vote plummeted by more than 9% to 27.6%, below the SDP's 25.4%.

In short, the electorate rejected Labour's plan to "do the things crying out to be done in our country today".

In particular, Foot's attempt to unilaterally scrap the UK's nuclear weapons, while the Cold War was still hot, and his proposal to withdraw from the European Economic Community (EEC), a predecessor to the European Union (EU), were unpopular.

How the Labour has changed. Now the party wants to stay in the political and economic union, while facing tough opposition from an insurgent and Euroscepitc Ukip in the north of England.

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.