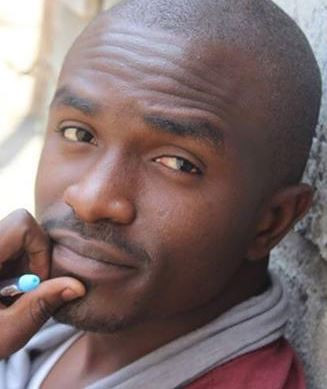

Law and disorder in the DRC: Who is Fred Bauma, Congo's jailed Mahatma Gandhi?

In just 15 days, Fred Bauma, the most prominent activist in the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC), will have spent exactly one year in detention on trumped-up charges.

This hollow anniversary will come as the 26-year-old is awaiting a private hearing at the Supreme Court regarding his provisional release – something that keeps getting postponed. The last time,he was told his file had not been transferred from the Court of Appeal to the Supreme Court."I'm starting to wonder if this is not done knowingly," Bauma told IBTimes UK exclusively through his lawyer.

Bauma's beginnings

Bauma's story is akin to that of the Great Lakes region over the past two decades, he says. Born to a working class family linked to traditional chiefs in Goma (the provincial capital of North Kivu) ,he completed his school and university education there.

His father had been involved in politics, meaning that Bauma was naturally interested in Congo's political affairs and activism from a young age. He was involved as an activist in a number of organisations, including the Youth Parliament. Before starting university in October 2012, he helped young people in his neighbourhood to find solutions to issues in the area when war against the M23 rebels broke out. "That's when I met a lot of my friends who were already involved in the Lucha [movement]." Lucha (Lutte pour Le Changement) is an opposition youth movement that was set up in 2012 in Goma.

East Congo has been gripped by war since the 1990s and there has been a repetition in uprisings that have more or less followed the same path: people rose up supposedly to liberate the population and received the support of neighbouring countries who often intervened, stealing, killing and massacring scores of people along the way. Rebels were either pardoned or received jobs in government or army ranks before becoming leaders of the populations that they slaughtered.

When the M23 were formed, young people like Bauma had already witnessed two political armed militias, the Rassemblement Congolais pour la Démocratie (Congolese Rally for Democracy, or RCD) and the Congrès national pour la défense du peuple (National Congress for the Defence of the People, or CNDP), whose key players found themselves in government. "In villages that had faced executioners, it was those executioners who had become their 'protectors'. That was a situation I could not accept," Bauma explains.

Why is Bauma fighting for change in Goma?

Extreme poverty has long plagued Eastern DRC, and the mineral-rich country as a whole. In Goma, a small town located near Lake Kivu, a water company is in operation, yet between 60% and 70% of the population have no access to drinking water.

The lake is rich in methane gas that could be used to produce electricity, but over 70% of the population does not have access to power. Despite the government's promises to build 30km of roads in the last eight years, no more than 10km were built. The DRC is two-thirds the size of Western Europe, but has fewer paved roads than Luxembourg.

"It [Goma] is also a town where the majority of young people who finish their studies have nothing to do – as unemployment is very high – even if there could be plenty opportunities," Bauma says via his lawyer.

"All these reasons prompted me to start fighting for change, but having young people doing their own things separately in their own associative movement was not effective enough, and did not bear the fruits we wanted." That's when Bauma joined the Lucha to ensure more action and meaningful change. "It was not the organisation that counted the most, but the citizens who were claiming their rights and to be heard."

In its first year, Lucha's actions and campaigns focused on access to water and the construction of roads. "We had some successes with petitions and campaigns in town and online, we met members of the parliament and the government. Every time we pressed for results, we noticed that 2km or 3km of roads were built, but as soon as we stopped, they also stopped building. But these little victories led us to believe that we could change some things as long as we were implicated and active and refused to endure the shortcomings of our government."

A history of violence in eastern DRC

What also fuelled Bauma's desire to keep faith with the group was its preferred method of non-violent resistance, like Mahatma Gandhi, who successfully pioneered this philosophy to overthrow British rule in India. Like Gandhi, Bauma is fighting for the right to true self-determination – free from a sham democracy, malicious international intervention and Western mining interests.

"It is something new for people in the region and many still don't understand that, because many in the area have used violence to resolve their problems. At times in north Kivu, violence has been the easiest way to access positions in the government, public companies or the army," he explains.

"We chose exactly the contrary because, when those leaders ended up taking advantage of the situation, the population was the one suffering, being displaced, dying and innocent women being raped – and we never saw any change. We also knew that campaigning in that non-violent way would expose us to more risks – as has been the case."

Extreme detention conditions

After getting in touch with other youths across the country to launch a nationwide movement as elections approach, Lucha organised a pro-democracy youth workshop in March 2015 with Filimbi, Balais Citoyen and Movement Yamana about civic engagement.

On the third day of the Kinshasa-based workshop – destined to launch Filimbi, a platform to encourage Congolese youth to peacefully and responsibly perform their civic duties – Congo's National Intelligence Agency (Agence Nationale de Renseignements, or ANR) arrived in three Jeeps and arrested about 30 pro-democracy activists and others. Among them were Senegalese and Burkinabe activists, a US diplomat, foreign and Congolese journalists, activists, musicians and artists.

The authorities released most of the detainees in the first week, but Bauma and Yves Makwambala, a webmaster and graphic artist, were held after spending one night in a cell at the Prosecutor-General detention centre.

"There, detention conditions are among the worst conditions I have witnessed during this long journey," he recalls. "The cells are extremely dirty – where you sleep is almost the same place where you defecate, you find yourself living with criminals accused of many things.

"When I got there, for example, there were street kids who were accused of having sliced off the hands of policemen – they smoke all sorts of drugs and are prone to violence. At the same time, you have extremely corrupt policemen, who will make you pay for anything and nothing. For between $50 and $200 for example, they can offer you to sleep outside of those disgusting cells. We are not given water or food during our detention. They just don't care about the conditions in which you are detained there."

Following his arrest, Bauma's lawyer said the activist spent 50 days in solitary confinement in an ANR cell, mostly without access to his family or lawyers.

After that period, he was transferred to Makala Prison, where authorities informed him of the charges he faced. These included: belonging to an association formed for the purpose of attacking people and property, forming a conspiracy against the head of state and attempting to either destroy or change the "constitutional regime" or incite people to take up arms against state authority.

"The authorities have also charged me with disturbing the peace," Bauma reveals. The current president, Joseph Kabila, stands accused of seeking to undermine the constitution by holding on to power beyond a second full term.

Hoping for justice to be served

Bauma currently shares his cell with Makwambala, and his lawyer reported him as saying he spends most days reading and writing to avoid being outside, where he fears he could be exposed to brutality. "You can very easily be attacked," he explains.

He also recalls the stress he is under – particularly after hearing about news of repression and crackdown on his friends and colleagues. "Each time my friends get arrested, it always feels like a lot of pressure on me". His issues are further compounded by the fact that Kinshasa is around 2,000km from Goma, where most of his family still lives.

"I am not losing hope, I know it will be a long fight and it is a risk we took to be able to defend the values that a lot of Congolese politicians don't want to hear about. We know that, in front of us, we have a government that does not hesitate to use the army or police to repress demonstrators."

Bienvenu Matumo, one of Bauma's closest friends in Kinshasa, was one of two activists arrested in the capital last week ahead of the Ville Morte day of action. "His arrest is like a second arrest for me, because he was the one helping me, running errands for me and would help maintain contact with the rest of the world."

Bauma says he is not losing hope that he will one day be released, but he casts doubt over whether justice will be served. "In DRC, we are in a situation where justice is entirely in the hands of politicians and the executive: judges and magistrates clearly receive orders from the government. I noted that during the hearings of other activists who are at times sentenced despite the fact there is no evidence against them," he says, pointing to the harsh sentence handed down to six Lucha activists last week.

"I've felt that way since my arrest, throughout my time in prison and when I had my case brought up before the Court of Appeal. I feel this lack of will for them (justice) to apply the law. It is not a just trial, we are faced by the repressive hand of the executive, who uses this justice to repress what is going on in Goma with activists arrested."

He continues: "However, I am not losing hope, I know it will be a long fight and it is a risk we took to be able to defend the values that a lot of Congolese politicians don't want to hear about. We know that, in front of us, we have a government that does not hesitate to use the army or police to repress demonstrators."

Non-violence must prevail

Since Bauma's arrest, the EU and Congolese and foreign personalities alike have called for his release. "I don't know why they keep blocking [my case] but that doesn't surprise me either, it's normal in a dictatorship. There is a saying that goes: when the dictatorship becomes the rule, the place of those leading just fights can only be prison."

Speaking of Lucha and similar activist group Ville Morte, Bauma expresses delight at the results –Kinshasa and Goma experienced paralysis during the widely observed general strike, despite threats from the government against participants including civil servants who didn't turn up to work and tradesmen who didn't open their stores.

"It's a beautiful and strong message that the opposition, civil society and the people have shown to our leaders. That they had the courage to stay at home during this period is encouraging, it's a clear message that the authorities and the international community should understand: 'We want elections at the end of this year as outlined in our constitution, we want political change, we want more democracy and liberty, and the more repression there will be, the more creative non-violent ways to get our message across'," he says unequivocally.

Recent crackdown on Lucha activists – who have vowed to remain non-violent – poses a danger, according to Bauma. "It's incredibly important to inform the international community about the risks of this type of action, because this is a region that has been through a lot of violence, and if we don't give the chance to those who are trying to only use peace and non-violence, we really face the risk of giving good reason to whoever wants to use violence that he is allowed to do so to get solutions," he warns.

"If the government squashes the Lucha, this not only means the failure of the Lucha, but the failure of non-violence, which is extremely dangerous. We want people and the international community, to act or react to this before time is up."

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.