Lee Rigby Murder: Why Giving GCHQ More Surveillance Power Won't Stop Terrorists

Following the attack on the Twin Towers in New York on 11 September, 2001, there was an immediate, knee-jerk reaction from people in the US to give the government's spying arm, the NSA, whatever powers it needed just so long as something like that would never happen again.

The result was PRISM, the NSA's mass electronics surveillance programme which Edward Snowden laid bare in 2013 in a series of high profile leaks, revealing what was seen by many as a huge invasion of privacy.

The problem with the NSA is that not only does it invade people's privacy, but these broad surveillance powers just don't work.

Despite turning the surveillance dial up to 11, in 2013 Chechen brothers Dzhokhar and Tamerlan Tsarnaev set off two bombs at the Boston Marathon, killing three bystanders. Two years earlier the FBI had been informed that Tamerlan had travelled to Russia and might pose a threat to US national security.

Despite having this information, the US agencies could not join the dots and prevent the Boston Marathon bombings from taking place.

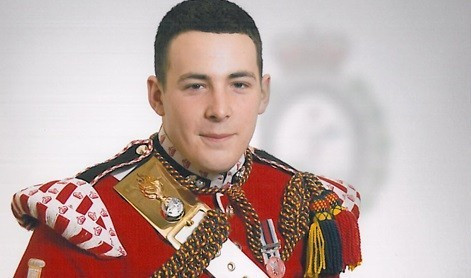

Fast-forward to November 2014 and the publication of the Intelligence Security Committee's (ISC) inquiry into the horrific and tragic murder of fusilier Lee Rigby by Michael Adebowale and Michael Adebolajo in London in 2013.

Who is to blame?

Among the many MI5 and MI6 failings highlighted in the report, the ISC seems to lay the blame at the door of an unnamed North American internet company which failed to pass on the fact that it had shut down several of Adebowale's email accounts for "terrorism-related" reasons.

Update: According to the BBC, Facebook is the website which hosted the interchange.

The report is pretty clear on where the blame lies: "This is the single issue which – had it been known at the time [December 2012] – might have enabled MI5 to prevent the attack."

The problem, as the ISC report sees it, is that the Regulation of Investigatory Powers Act (Ripa) doesn't go far enough in allowing the British government's spying arm, GCHQ, to demand such information from companies not based in the UK.

Too much data

This, on the face of it, seems like a reasonable conclusion. Adebowale's emails specifically referenced "killing a soldier" so had that information been made available, then MI5 may have made him a 'Priority 1' suspect at the time, meaning the murder could have been prevented.

The result has led to calls for increased powers such as those to be outlined by Theresa May in Parliament on 26 November in a new counter-terrorism bill.

While having this information may have prevented the attack, it is just as likely not to have helped at all.

The problem for GCHQ is not that they don't have enough data - it's that they have too much.

The report states that GCHQ has direct access to "major internet cables" and has systems in place to monitor communications as they "traverse the internet" - yet despite this, it still couldn't prevent the Lee Rigby murder.

GCHQ drowning in data

The report slammed MI6's "apparent lack of interest" in Adebolajo's arrest in Kenya in 2010, despite him apparently preparing to fight alongside Somali militant group al-Shabab.

It was as far back as 2008 that he was first identified as someone who should be prioritised, but at the time someone else emerged as more important and interest in Adebolajo waned.

This is the crux of the problem - GCHQ is drowning in data and doesn't have the resources to adequately analyse and pick out what is important.

The report says: "The resources required to process the vast quantity of data involved means that at any one time, GCHQ can only process approximately *** of what they can access."

Demanding more data from the likes of Google, Yahoo, Facebook, Twitter and other internet companies based outside of the UK 'could' help prevent more atrocities like the murder of Lee Rigby, but as we have seen already, it is not a lack of information which is the problem for the intelligence community, it is a lack of real insight and an inability to connect the dots.

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.