Looking past Trump vs Clinton shenanigans: The case for investing in US stocks

It is worth remembering that US stocks represent a bit over half of the value of all quoted companies in the world.

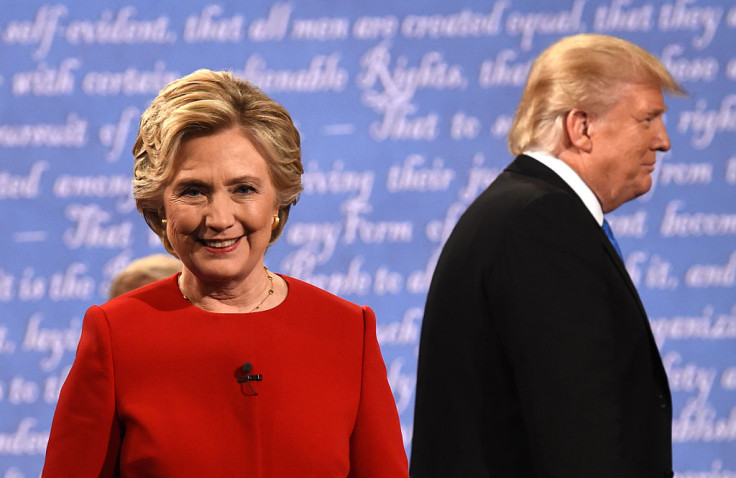

The increasingly acrimonious war of words between Hillary Clinton and Donald Trump has dominated the headlines in recent weeks. There is no love lost between the two candidates as the 8 November US presidential election approaches.

For investors outside the US, however, politics has been a sideshow. What has mattered more has been the dramatic moves in the foreign exchange markets. Of the six North American funds on Fidelity's Select 50 list, five have given investors a currency-fuelled gain of more than 30% over the past year. The worst performer has still risen by 28% in sterling terms.

Politics matters – especially when candidates offer such differing world views – but sometimes it can be a distraction from what ultimately drives financial markets. Investors acquire a share in companies' profit streams. In the US in particular, politicians' ability to influence these can be limited.

That is because the US political system is almost expressly designed to cap the ability of the president to push through an agenda. The division of power between the White House, Congress and the Supreme Court often leads to gridlock. That sounds bad, but in reality markets tend to prefer inactivity on Capitol Hill – it lets companies get on with what they do best, building their businesses and growing profits.

The best outcome for investors is invariably a divided government, which meets deadlines on budgets and debt limits, for example, but struggles to legislate on anything more significant. In the run up to the election, the S&P 500 has performed best when the most likely outcome looked to be a Clinton White House but a Republican-dominated Congress.

On the basis that the outcome of the election is less important than the news headlines might suggest, what's the ongoing case for investing in the US stock market? Pretty good, I think.

Wall Street has led the global market recovery since the dark days of 2009, when the S&P 500 hit a low of 683 in the wake of the financial crisis. The benchmark US index has trebled in value since then.

This is not all that surprising when you consider that America moved more swiftly than its developed market counterparts to re-capitalise its banks and to implement the radical monetary policy that helped avoid a repetition of the Great Depression of the 1930s.

The consequence of the US market's leadership of the rally is that American shares are more expensive than pretty much any other market. That has raised questions about whether the S&P 500 can maintain its lead, especially in the absence of strong earnings growth. My view is that Wall Street deserves its premium for a whole host of reasons.

First is the sheer size and stability of the US market. Its weighting is six times that of the second biggest market, Japan. American stocks represent a bit over half of the value of all quoted companies in the world. Not only is the market large, it is also less volatile than its main rivals. The swings in the S&P 500 tend to be less pronounced than in other markets.

The US stock market is also exposed to some of the fastest growing sectors in the world. Technology and healthcare, in particular, are areas of strength. They benefit from the high levels of innovation in the US economy. US shares represent around three quarters of the global IT index, for example.

One of the key worries about the US, has been the outlook for interest rates, but here too I think concerns have been overdone. At the beginning of this year, the Federal Reserve expected to raise interest rates four times in 2016 but we are still waiting for even the first of these hikes.

The Fed is likely to remain cautious for the foreseeable future and the normalisation of monetary policy will be slow and steady.

That will continue to provide support to the biggest and most influential part of the US economy, domestic consumption. This is a key driver of US GDP, contributing around two thirds of all growth. With unemployment at historic lows and a healthy housing market, the outlook remains favourable on this front.

Monetary policy has been a big help in recent years and may well have run its course in the US, as elsewhere in the world. There are, however, other levers that can be pulled to stimulate growth. American infrastructure is increasingly aged and, after years of underinvestment, this could provide a significant boost in years to come.

America's economy has many tailwinds. Perhaps the most important of these is the country's creativity and innovation. Eight out of 10 of the world's biggest technology companies are American. The country dominates global research and development spending and has more scientists and engineers per head of population than any other country.

Other advantages include a favourable business environment, positive demographics – it is younger and more dynamic than either Europe or Japan – and a powerful energy sector that is close to achieving independence from the world's most troubled region, the Middle East.

So the investment story is compelling. The only question is whether investors are paying too much for the good news, with earnings multiples generally higher than in most developed markets.

I think the valuation premium is justified. In absolute terms, valuations are high but not excessive. And relatively speaking, US shares look much better than most alternatives, notably bonds.

America should continue to be a significant part of any well-diversified portfolio.

Tom Stevenson is Investment Director for the Personal Investing business at Fidelity International. Tom joined Fidelity in March 2008. He acts as a spokesman and commentator on investments and is responsible for defining and articulating the Personal Investing business' views. Prior to joining Fidelity, Tom was a financial journalist writing for various publications including Investors Chronicle, The Independent and The Telegraph.

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.