Margareta Pagano: George Osborne happy to borrow Swedish budget ideas in lieu of borrowing money

"What Sweden does today, the world does tomorrow" is an old saying that the Swedes love to boast about. They have many reasons to be proud - for a tiny country they've produced some stunning legacies, from the darkest Nordic Noir novels to Abba, Volvo cars to cheap and cheerful Ikea furniture (and let's not forget the meatballs) - all of which have been imitated elsewhere and gone global. And they come up with the best Eurovision songs too.

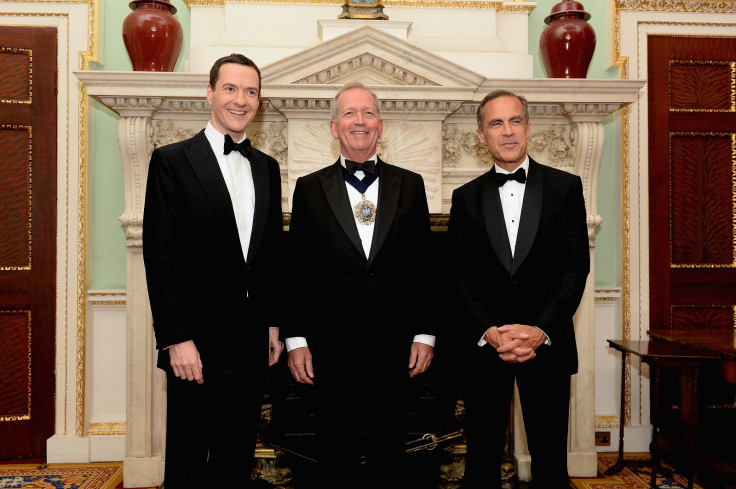

Now Chancellor George Osborne has stolen another Swedish innovation with his new proposal for a budget surplus target - a new fiscal settlement to enshrine in law a commitment to run a permanent surplus.

Borrowing again, this time from the Victorians, the Chancellor will also resurrect the Committee of the Commissioners for the Reduction of the National Debt: a committee of heavy-weights made up of the Chancellor, the Governor and Deputy Governors of the Bank of England, the Lord Chief Justice, and the Speaker of the House of Commons to uphold the law. Created by William Pitt the Younger to reduce the national debt, the committee last met in October 1860.

You have to hand it to Osborne, he knows how to come up with the most cunning of traps with which to ensnare his opponents. How can the opposition ever argue against fiscal responsibility after the election rout?

As the Chancellor pointed out when announcing the new proposals at the Mansion House on 10 June, the recent British election result was a "comprehensive rejection" of those who argued (the two Eds) for more borrowing and more spending.

He's right. Can you imagine any of the wannabe Labour leaders standing up in parliament in a few years time arguing that such a noble cause as keeping a permanent budget surplus is no longer the right thing to do? They would be shouted out of town unless, of course, there were to be another financial crash or some other unforeseen disaster that would change the landscape.

If that were to be the case, Osborne would also be able to change his mind and borrow from Harold MacMillan's supposed famous speech in which he said, when asked about the difficulties of his job: "Events, dear boy, events."

He's already half-prepared himself for the unforeseen by suggesting that such a new framework would allow a deficit in times of recession, or not in "normal times." So he's covered himself.

The Chancellor has also been nifty in the way he has made the new settlement as tough as he can for the opposition to reject as he's suggesting a Commons vote on the issue rather than needing new legislation (because that would take time and could get lost in the woodwork of both houses.)

He's also making it harder for any future government to break such a promise because to stop running the surplus, they would have to make their case to parliament.

Politically, Osborne's ruse is clever. But do the economics of the rule work? Does it hold water? When the Conservative-led Coalition came to power in 2010, Britain's budget deficit was more than 10% of GDP and there's no question that the public's cynicism of the previous Labour government's spending plans were a big reason for them not gaining power at the last election.

More pertinently, Ed Miliband's refusal to ever acknowledge properly or apologise for Labour's over-spending was a weeping sore that was allowed to fester and ultimately cost them the election.

While Britain's budget deficit was down to just under 5% of GDP last year, this is still larger than that of most other advanced economies and the government quite correctly is determined to bring the deficit down within three years.

It's no surprise that Osborne's humdinger is being greeted with mixed reactions; economists on the left claim that requiring a balanced budget every year is too tough a target while the International Monetary Fund recently warned countries not to shoot themselves in the foot by getting debt down too quickly.

Others ask why would Britain want to run a surplus, particularly when we have such an ageing population? Surely a balanced budget is enough to go for?

But that doesn't mean it's not the right approach, and we should applaud the Chancellor's attempt at prudence - it's never the wrong time to do a good thing.

Even the clever Swedes have had to change their surplus target. In March this year the Swedish government proposed ending the target – created in 1997 – because it wanted to free up money for public infrastructure projects to help keep down unemployment to the lowest level in the EU.

But before you leap to the obvious conclusion, just wait to hear what they want to change. They want their National Institute of Economic Research to look at whether a balanced budget target would be fairer than the present 1% surplus over the economic cycle.

If the new Labour leader wanted to outsmart Osborne, then maybe they should go for the full Swedish smorgasbord?

Margareta Pagano is a business journalist who writes for the Independent and the Financial News. Follow her on Twitter @maggiepagano.

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.