Minsk ceasefire deal: Will the Ukraine crisis kill Nato?

The Ukraine crisis is something of a litmus test for Nato, the ageing transatlantic defence alliance formed at the dawn of the Cold War to shield Europe from the Soviet Union.

Its hawkish critics have decried what they see as a weak response to Russia's annexation of Crimea and its military support for warring separatists in the east of Ukraine.

But others welcome any weakening of Nato, an organisation they see as creating more conflict than it prevents and a tool for American imperialism.

The leaders of Germany and France – both Nato members – and Ukraine and Russia met in Minsk, Belarus, to try to reach a last-minute diplomatic deal to stop the fighting and re-establish peace. They agreed a fragile ceasefire. But there was no deal on borders or autonomy for rebel-held areas.

Should that ceasefire fail, as many expect it will, the leaders of Nato's 28 member states must again ask searching questions on how to take on the Russian president Vladimir Putin over his actions in Ukraine. Will the organisation expose itself as a grand illusion?

George Weigel, a US foreign policy commentator, wrote in Standpoint magazine:

Vladimir Putin's Russia, a kleptocratic, Mafia-like police state sitting atop a crumbling society, is nonetheless poised to dismantle the fundamental international security architecture that has kept the West safe since 1949.

The decisive test may well come over the next few months in the Baltic republics; if Putin, using his now-familiar excuse of ethnic and nationalist solidarity and his now-familiar tactics of the Big Lie and destabilisation by special forces, takes a bite out of Latvia or Estonia, what will Nato do?

Despite its solemn obligations under Article 5 of the Nato treaty to regard an attack on one member state as an attack upon all, the most that can be expected from the Obama administration, on its record, will be further economic sanctions.

The few European states willing to face down Putin will find no American leadership to follow; Article 5 will thus be rendered null and void; and that will mean the de facto end of history's most successful security alliance — and the abrogation of the victories it won in 1989 and 1991.

Sanctions and reinforcement

The West has imposed financial sanctions on Russia for its aggression in Ukraine, where the crisis death toll is approaching 5,000 as war between Kiev and pro-Russian separatists tears through eastern cities such as Donetsk and Luhansk. Russia retains control of Crimea, which it annexed in March 2014.

Russia has retaliated with sanctions of its own. But it is suffering more than the West. Russia's economy will contract by 4.5% in 2015, according to a forecast by its central bank, in part as a consequence. It is also suffering because of falling oil prices.

For its part, Nato has developed a "Readiness Action Plan" (RAP) to make its troops more prepared to respond to sudden crises, including an ultra-ready "Spearhead Force" of 5,000 ground troops. Altogether, Nato said it will have 30,000 troops under its "enhanced" response force.

Nato Secretary General Jens Stoltenberg said at the time:

If a crisis arises, they will ensure that national and Nato forces from across the Alliance are able to act as one from the start.

They will make rapid deployment easier. Support planning for collective defence. And help coordinate training and exercises.

Nato has also deployed more troops to its European allies, such as sending fighter jets to the Baltic states, and increased its patrols under the plan. Stoltenberg has described the RAP as "the biggest reinforcement of our collective defence since the end of the Cold War".

But Nato states have made clear that it will not send troops into Ukraine, which is not a member state, though it is a partner and Kiev has long had aspirations of joining the organisation.

Angela Merkel, the German chancellor and de facto leader of the European Union (EU), said the solution to the Ukraine is a diplomatic not a military one after her meeting in Moscow with Putin.

And Barack Obama, president of the US, has said that he "will look at all additional options that are available to us short of military confrontation".

Are Nato's critics right? Has it responded weakly to the Ukraine crisis and Putin's actions by not committing troops to Kiev?

Alex Nicoll, senior fellow for geo-economics and defence at the International Institute for Strategic Studies (IISS), tells IBTimes UK:

Obviously this wasn't something that Nato expected to be having to do.

From the time that the Ukraine crisis was serious, I think Nato has responded in quite significant ways by the things that we know about.

Clearly, Nato leaders are not interested in intervening in Ukraine itself. I think they've made that quite clear and I think that's still the position, in spite of all the talks we've been seeing.

He added that Nato's primary concern has been to reassure its former Soviet bloc members – many of which have large ethnic Russian populations similar to Ukraine – of their guarantee to security. But Nicoll is not convinced that Putin has shown the desire to invade other states.

Dr Rowan Allport, a senior fellow at the Human Security Centre thinktank, tells IBTimes UK:

It is important to separate Nato's core responsibly as an organisation focused on the collective defence of its members from the secondary, post-Cold War role it has adopted as a regional security actor.

At present, whilst there are many divisions amongst Nato states regarding the handling of the current crisis in Ukraine, there is no sign of any fundamental fracturing of the security guarantee membership of the organisation provides.

Allport says this is reflected in Nato's recent actions, such as the Readiness Action Programme and deployment of forces to Baltic states.

However, there can be little doubt that is falling some way short in its regional security role. In part, this is because the challenge Russia presents is far larger than those faced in the former Yugoslavia, Afghanistan and Libya - Nato's largest previous operations to date.

However, there is also an across-the-board lack of political resolve to confront security challenges amongst the key member nations that has not been seen in a generation.

At the very least, it would seem sensible that Nato, or more accurately the organisation's core membership, should be enhancing their efforts to support the reform and training of Ukraine's armed forces, which were hugely weakened by the corruption of Kiev's previous pro-Russian government.

'Nato foreign legion'

President Poroshenko of Ukraine has stopped short of calling for Nato to put boots on the ground, perhaps because he has been told behind the scenes not to bother. But he has asked for "lethal defensive arms" to help equip his army in the fight against Russia and pro-Russian rebels.

Putin, however, already thinks Nato troops are on the ground in Ukraine. Speaking to students in St Petersburg, he called the Ukrainian army "a foreign legion, in this case a foreign NATO legion, which, of course, doesn't pursue the national interests of Ukraine."

Paradoxically, Putin needs a strong Nato – or at least the perception of its strength to exist – because it is his claims of antagonism by the organisation that underpin his arguments for the Kremlin's own military aggression.

But, argues Nicoll, one thing is for sure: Ukraine won't be joining Nato anytime soon.

Ukraine is not a Nato ally and is not really right now on the cards of being a Nato ally.

Obviously that's what the Russians suspect. They are obsessed with this idea that Ukraine and previously Georgia could become Nato allies. But we have to look at the reality and say that that's really not on the cards. Nobody is really arguing for that right now.

Perhaps out of these talks going on right now there might even be some kind of assurance to Moscow on that. I don't know.

Pathetic

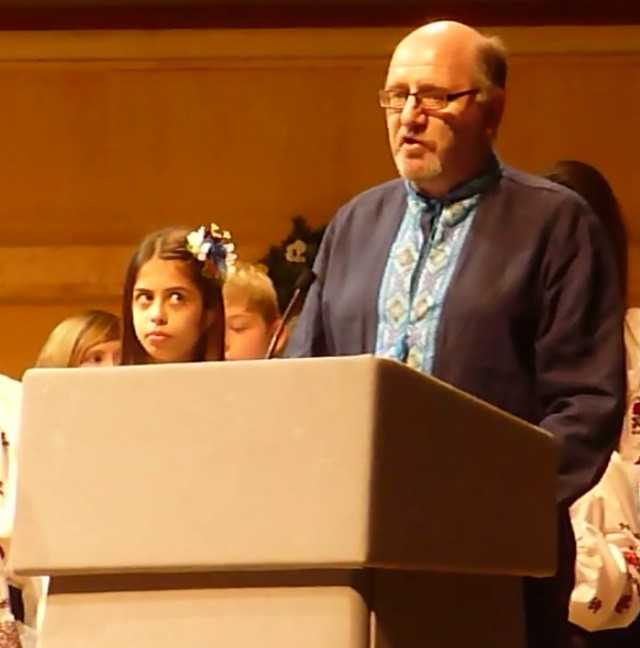

Zenko Lastowiecki is president of the Association of Ukrainians in Great Britain (AUGB). He has family in the west of Ukraine and is worried about the prospect of total war if the situation escalates any further. Soldiers are already being drafted from all over Ukraine.

Lastowiecki tells IBTimes UK:

As you can imagine, for someone with very close connections with Ukraine, it's worrying. But by the same token, I think it's necessary.

Ukraine has to defend its territory otherwise President Putin is just going to roll over it.

The AUGB has been collecting money for supplies to be sent to the front line in Ukraine: food, clothing, first aid kits, medical equipment. All much needed by Ukrainian soldiers and civilians in parts of the country's east.

But Nato's response so far, Lastowiecki says, has been "pathetic".

There's too much procrastination. I understand the West is trying to negotiate some kind of treaty. But that's been tried and failed," he says.

Yes, I agree with Angela Merkel that you should give diplomacy a chance. But the rhetoric coming out of the Kremlin is just not, as I can see it, a way out.

President Putin just adamantly denies any involvement whatsoever and the evidence is quite to the contrary, which makes it quite difficult to negotiate with somebody who doesn't even think he's at the party, let alone responsible for creating a lot of the problems in the first place.

Now his latest views are that it's all Ukraine's fault and the West for stirring it all up in the first place because they expand Nato when they said they wouldn't.

So he's just doing everything he can to blame everybody else except accept any responsibility himself. It's very difficult to negotiate with these kinds of people.

He just wants Nato to "stand up and stick to what it said it would do": honour the 1994 Budapest Memorandum.

Obviously Russia has blatantly disregarded that. But the fact that Britain and America have just walked away from that agreement says a lot," he says.

And they should actually now stand up and do what they say they're going to do.

Under the Budapest Memorandum, signed by Russia, the US and the UK, Ukraine gave up its nuclear weapons in return for assurances about its economic and political sovereignty and that it would not be the target of Western or Russian aggression.

Putin has already disregarded the Budapest Memorandum because he does not recognise the current Kiev government, which came to power after the corrupt pro-Kremlin president Viktor Yanukovich was ousted from office during violent protests against him.

Yanukovich had eschewed closer trade ties with the EU – which is what many Ukrainians had wanted – in favour of joining Russia's rival Eurasian Economic Union after Putin put pressure on him. This is what triggered the protests, his ousting and Russia's subsequent annexation of Crimea.

Still in demand

The response of Nato to the Ukraine crisis was always going to be too much for some and not enough for others. But there remains a question about the role of Nato in the future as it emerges from its focus since 2001: the Afghanistan War.

It was an unpopular conflict that dragged on for years and cost thousands of lives, mostly those of innocent civilians. Coupled with Iraq, which was not a Nato conflict but led by its most powerful member, the US, the organisation's name has been sullied in the public eye over the past decade.

Nato evolved from a collective defence shield against the tyrannical Soviet Union into a global police force which concerned itself with radical Islam in the Middle East after the 9/11 terror attack on the US.

Now it is retreating back into its original territory with the outbreak of the Ukraine crisis coming at the end of the Afghan war. But has Nato forgotten its original purpose?

Nicoll of IISS says:

There's not a strong awareness of defence issues in general in many Nato countries, in Europe at least.

And that's just a fact of life. When you've got a continent that's been basically at peace for a long time and there are competing demands on national budgets and agendas, it's inevitable that defence is going to take a bit more of a backseat.

I think it has been difficult for Nato's issues to rise to the top of the agenda of European Nato member governments.

But Nicoll adds that what he has noticed is that people always turn to Nato for a response to emerging crises. Take Libya and the fall of Gaddafi, for example. Or the Islamic State, which Nato has targeted with a campaign of airstrikes.

I don't necessarily mean the man in the street, but the man in the street's democratic representatives, if you like," he said.

So I still think for governments, even if it's not top of their minds, that it's still a highly useful instrument for them.

What happened last year was quite illustrative in that there was a Nato summit in Wales, of course it was known for about a year in advance that there was going to be one, the initial emphasis was that there wasn't going to a really very exciting summit.

The focus was going from deployment to preparedness as the Afghan mission wound down, but then the Ukraine crisis came along and European security was the top of the agenda and they did in fact take some important decisions there.

So the leaders found it useful as a means of demonstrating solidarity.

In the future, Nato must deal with declining defence budgets, especially in Europe where austerity and low economic growth are tearing through national budgets.

Nato members are recommended to spend 2% of their GDP on defence. Just six, including the US and UK, met this standard in 2013, according to World Bank data.

Nicoll says:

There are challenges, for sure, in that spending is in general on the decline and that makes it more difficult to invest in the technologies that are going to be the technologies you want in future conflicts for future crises.

That puts pressure on countries to co-operate more on whether it's on actual force structures, or buying equipment, and actually they haven't been very good at that. Co-operation has not nearly advanced as much as it should.

Each time defence spending falls you think that will encourage real co-operation. And then it doesn't really happen.

Nato is still a powerful force in the world. Security demands and expectations continue to be made of it. But this will be less so in a global sense than recent years.

It's still a tie to the United States, which for Europe is still very important in terms of keeping America interested in preserving European security.

There was a discussion a few years ago about whether Nato should become more global and basically the answer was no. Countries didn't want it to. So Afghanistan might be the furthest it goes.

Misguided opportunism?

After Putin's Georgia adventurism in 2008, in which he annexed the region of South Ossetia, and now his aggression in Ukraine, the Russian expansionism of the past appears to be rising from the dead.

Some Kremlin-watchers believe Putin is testing the limits of the new geopolitical order amid perceptions of a weaker, more insular US under Obama. Essentially, Putin looks to be seeing how much he can get away with by asking questions of the West and Nato's appetite for conflict.

How far are he and Nato willing to go?

Allport of the Human Security Centre says:

It is difficult to predict Putin's ultimate intentions. Whilst it is easy to slip into the notion that he has some sort of master plan - or at least the vague outline of one - it is equally probable that he simply an opportunist who is essentially making things up as he goes along as part of a broad strategy of sowing division amongst the Western allies using all of the means at his disposal.

In isolation, the Baltic states are of little strategic use to Russia, and at present it seems inconceivable that any direct or indirect incursion into them would fail to provoke a reaction from Nato that would ultimately prove to be catastrophic for both Russia and Putin personally.

However, it cannot be ruled out that Putin will act in a way that does not reflect a rational interpretation of Russia's interest. Arguably, his actions in the Ukraine have already seen him cross this line.

Allport adds:

In intervening in the Ukraine, Putin has arguably given Nato - an organisation that was facing the post-Afghanistan era with dread - a clear purpose, and in doing so has unintentionally helped preserve its strength.

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.