Much-needed criticisms of government are being drowned in Labour's embarrassing publicity

Way back in 1987, I had lunch with a member of Margaret Thatcher's cabinet who surprised me (if not knocked me right off my chair) when he suddenly said: "I don't think any party should be in office for too long." He went on to say that such a situation was bad for democracy and he for one would not mind if Labour won the next election.

What was especially interesting for me was that my interlocutor was not one of "the usual suspects", that is, one of the so-called "Wets" who were often critical of Thatcher's harsh approach to the economy.

Indeed, the deflationary monetarist policies of the early 1980s had been so harsh, contributing to the worst recession and highest level of unemployment experienced in Britain since the Second World War, that Thatcher had become the most unpopular British prime minister since records began.

She would almost certainly have lost the 1983 general election but for Britain's successful repulsion of the Argentine invasion of the Falkland Islands in 1982. After that, in a blaze of patriotic rejoicing, the political tide turned.

Well, the Conservatives most certainly did not lose the election of 1987 either. Having been in office since 1979, they went on and on, proceeding to win the election of 1992 as well.

Now, after the Blair-Brown interlude of 1997 to 2010, the Conservatives are in their sixth year of resumed office. Meanwhile, the Labour Party seems to be in such a bad way that the general consensus among political pundits and, indeed, Conservative and Labour members of Parliament, is that the Conservatives will win in 2020 as well.

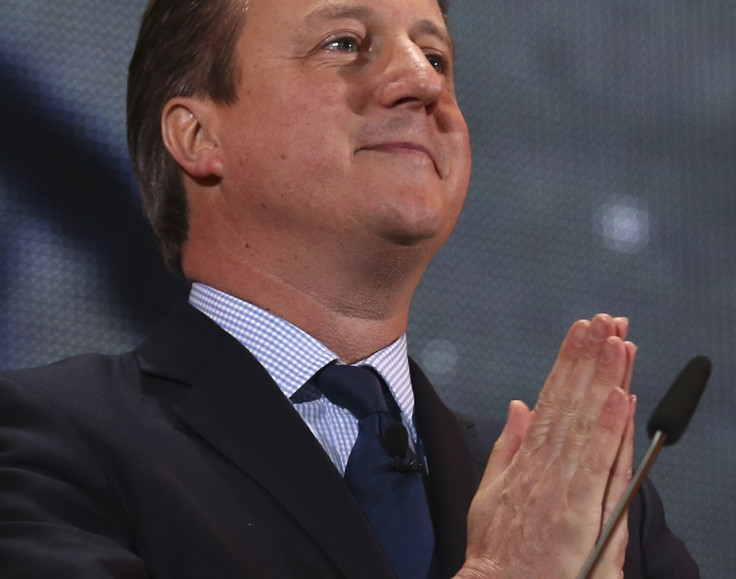

This is surely not good for democracy. Moreover, in my view the mission on which those in control of the modern Conservative Party are bent is especially dangerous. They want to shrink the size of the state to the point where even the constituents of Conservative members of Parliament are becoming concerned. The farcical situation was reached recently when even Prime Minister David Cameron was complaining to Chancellor George Osborne, the main champion of "austerity" about the impact of spending cuts in his own constituency.

Yet the problem for the Labour opposition is that their valid criticisms of the government are being drowned in the embarrassing publicity being given to the party's internecine strife.

Thus Labour's controversial leader Jeremy Corbyn made a stinging attack over the weekend on the way that the "austerity" programme is damaging the social fabric of the country – also on the way that various changes in the voting system are cynically calculated to drive young and inner city voters off the electoral register – hardly a blow for democracy.

However, most of the attention with regard to Labour focuses on Corbyn's desire for the UK to lead the way in unilateral nuclear disarmament. The truth is that it is not just "left-wing peaceniks" who are concerned about the wisdom and cost of renewing the Trident missile programme. Many in military establishment have their doubts as well.

But there is a difference between renewal of Trident and the full-scale disarmament envisaged by Corbyn. As that great Labour figure and former defence secretary Denis Healey used to say: "If your enemy has nuclear weapons, you have to have them too."

William Keegan is a journalist, academic, and the senior economics commentator at The Observer. He has published his latest work – Mr Osborne's Economic Experiment - Austerity 1945-51 and 2010 (published by Searching Finance).

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.