Nobel economics prize winner thought Academy call was spammer

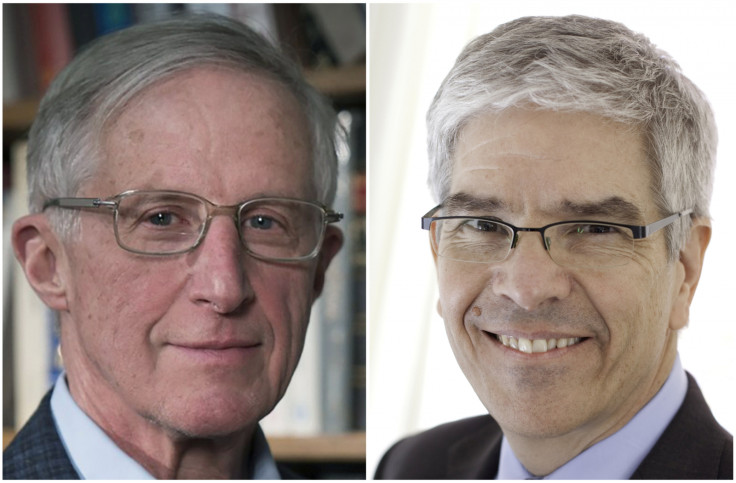

Two Americans won the Nobel Prize for studying a pressing issue facing the global economy: how to deal with pollution and climate change and how to foster the innovation needed to tackle such problems.

One of the winners of this year's Nobel Prize in economics says he ignored two telephone calls, thinking they were spam calls, before the Swedish Royal Academy of Sciences was able to get through to him.

Paul Romer of New York University said that on Monday morning "I didn't answer either because I thought it was a spam call."

Romer teaches economics at New York University, where he founded the Stern Urbanization Project, which researches how policymakers can harness the rapid growth of cities to create economic opportunity and undertake systemic social reform.

Romer's work "explains how ideas are different to other goods and require specific conditions to thrive in a market," the academy said. Romer's work found that unregulated economies will produce technological change, but insufficiently provide research and development; this can be addressed by government interventions such and R&D subsidies.

He won the prize together with William Nordhaus of Yale University for separate research.

Nordhaus in the 1990s became the first person to create a model that "describes the global interplay between the economy and the climate," the academy said. Working separately from Romer, he showed that "the most efficient remedy for problems caused by greenhouse gases is a global scheme of universally imposed carbon taxes."

Carbon taxes are fees imposed on companies that burn carbon-based fuels such as coal and oil. Advocates see the taxes as encouraging companies to use less-polluting fuels.

"This is, for sure, a Nobel Prize about the big questions," University of Michigan economist Justin Wolfers said on Twitter.

Per Stromberg, head of the Nobel economics prize committee, said "it's about the long-run future of the world economy."

"The first one is how do we keep on generating the new ideas, the new innovations, the new research that's so important to solve the problems we're facing in the future," he said.

"The second is how do we deal with the negative effects of economic growth, which have to do with the emission of greenhouse gases leading to a warmer climate - which not just hurts the economy, but risks the life of everyone on earth," Stromberg said.

The prize comes just a day after an international panel of scientists issued a report detailing how Earth's weather, health and ecosystems would be in better shape if the world's leaders could somehow limit future human-caused warming to just 0.9 degrees Fahrenheit (a half degree Celsius) from now, instead of the globally agreed-upon goal of 1.8 degrees F (1 degree C).

Nordhaus has argued that climate change should be considered a "global public good," like public health and international trade, and regulated accordingly, but not through a command-and-control approach. Instead, by agreeing on a global price for burning carbon that reflects its whole cost, this primary cause of rising temperatures could be traded and taxed, putting market forces to work on the problem.

Many economists have since endorsed the concept of taxing carbon and using this financial lever to influence societal behavior. But adopting the regulatory frameworks on a global scale has been a complex challenge, and the world's political leaders are failing to meet it, the head of the United Nations said last month.

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.