Nowhere to go: Calais' refugee children urge Britain and France not to forget them as Jungle demolition looms

Child refugees, some as young as eight, are easy prey for traffickers and criminals.

As 1,022 lone child refugees wait to learn their fate when Calais refugee camp is demolished in the coming weeks, Qais, from Afghanistan, no longer dreams of England. The 18-year-old, who has lived in the camp's squalid conditions for months, has spent eight months trying to stowaway on a lorry bound for the UK but has now opted instead to claim asylum in France.

"I like it here, [in] France. It has very beautiful people, very good people," he told IBTimes UK from Calais camp, known as the Jungle.

Qais, from Afghanistan's lawless western Herat Province, has spent seven of the last eight months in Calais trying to learn French and says that while his spoken language is passable, his writing is poor. He spent $3,000 getting to Europe to start a better life. "I had a job in Afghanistan. I didn't come for money but to study. I was studying chemistry – so maybe I'll work in a laboratory," he said.

But in the long term, Qais has not completely abandoned his hope of reaching the UK. In fact, he hopes that one day he can not only cross the Channel but be elected to the British parliament in order to help refugees like himself. "When I am minister, one day, here there will be no border, and no more camp," he said.

Qais may joke about becoming a member of cabinet, setting out policies to alleviate the suffering of refugees, but the young man said his decision to apply for asylum means he can now escape the Jungle and its violence. As he says so, he bends over and picks up the empty tear gas canister he claims was thrown on migrants by French police during the most recent clashes between security forces and refugees.

Hassan, 15, from Sudan and David, 18, from Eritrea

While some of the lone children are entitled to apply for asylum in the UK because of family connections, aid workers are urging French authorities to secure accommodation places for children who have no right to go to Britain, as little has been done so far to safeguard them.

Speaking of his exhausting journey from Sudan through Libya, Italy and France, Hassan, 15, said he will have nowhere to go once the camp is demolished and – pointing to other children standing around him – he warned hundreds like him would be forced to live on the streets. "Because I don't know anybody here in France, I don't know what I will do (when the camp is demolished)," he said.

As children "would not know where to sleep" many would face "bad things," he went on to say.

Walking through the camp, the helplessness is palpable. David, an 18-year-old Eritrean orphan who arrived in Calais after he fled political instability and violence, spoke of an increasingly desperate sentiment amongst the camp's 10,000 residents.

He described how every night the refugees and migrants in the camp would cut down trees and lay them in the road to slow cars and lorries heading for the Channel Tunnel. If the vehicles stopped, the men would try to board the lorries in a desperate bid to get to the UK. It is dangerous work: an Eritrean migrant was hit and killed on 9 October as he was erecting barriers to block passing cars on the A16 motorway.

Because of the violence and harsh abuse French and British people have given him in Calais and near the Channel Tunnel, the young man said his dream of reaching the UK has changed. "I need to go to Canada. All night, my dreams are about Canada, it is better than European countries, because they are accepting refugee people. If Afghans go to the UK, they get told there is no problem and then they get deported."

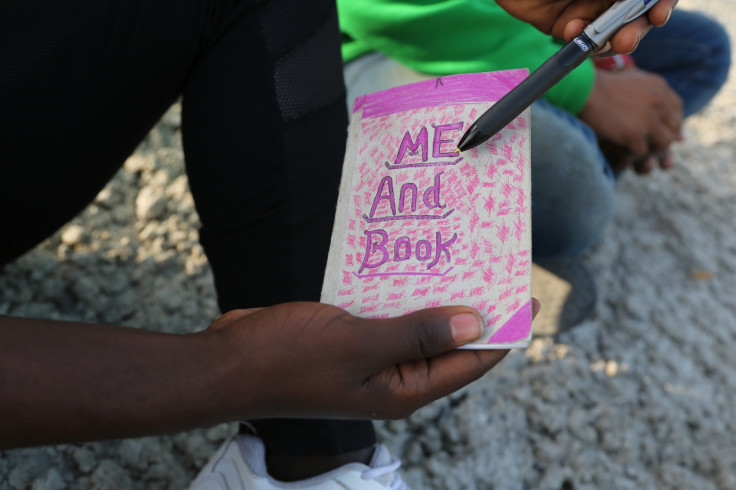

Calling over two young girls, also from Eritrea, David pointed to one of them, and proudly said he had found love in the camp. Pulling out a journal with which he walks everywhere and in which he writes down his thoughts, David said that if his new-found love cannot leave with him, he will be heartbroken.

Mamad, 16, from Afghanistan

His greasy hair and dirty feet may be synonymous with how difficult life in the camp has been, but after surviving these conditions for the last 13 months, Mamad, 16, said that the growing fears for the future have pushed him to the limit. The young Afghan is just one of many lone child refugees showing signs of severe clinical depression.

The teenager, who has been in the camp for over a year, said he has become apathetic and hopeless. He no longer follows the other children during their night-time attempts at climbing onto lorries.

"What kind of life this is? I have seen wars and have seen friends who were here with me, slept by me. Some of them went to London, some died," he said.

He described how his teenage cousin, who he travelled with when he fled Afghanistan, was allegedly shot by Iranian police during their journey. Mamad pulls out his phone and scrolls back and forth between two photographs of his baby-faced cousin.

Besides kidney problems that have gone untreated for nine months and injuries sustained after falling from moving lorries, Mamad said: "I have got mental problems as well (...) I am in great pain and trouble." His burning eyes seem to emphasise his claim that he is "going crazy".

"I get up at night time and weep," he said.

Gul, 15 and Zab, 14, from Afghanistan

Many in Calais believe that the UK has its part to play in saving them from the Jungle - even lone children with no ties to Britain. Gul, 15, and Zab, 14, who both asked for their faces not to be identified, said they had a message for the British government: let us come to the UK.

"If this camp is demolished, we will still be staying here till the time we are picked up from here," Gul said.

"My message to the UK government is to pick us from here and take us to London. Those having families can go there, but we don't have any family, father or elder there. We should also be taken with them."

Zab agreed that all Calais' lone children – the youngest of which is eight – deserved sanctuary: "If they are left here, they will not be of any use to their parents. They will be wandering in the forests."

Hamed, 15, Afghanistan

French President Francois Hollande announced the shut-down of Calais's refugee camp, located around 14.5km (9m) from the Channel Tunnel, in September but stopped short of issuing a date for the closure.

After France said Britain is not living up to its moral duty to take in more unaccompanied children, British Home Secretary Amber Rudd and the French Interior Minister Bernard Cazeneuve met in London on 10 October to discuss their protection before, during and after the planned dismantling of the camp.

Describing the safety of vulnerable children in Calais as "their utmost priority", British Home Secretary Amber Rudd said she would implement and enlarge the already agreed upon resettlement of isolated minors in Calais with established family ties in the UK.

While Citizens UK had previously identified 387 refugee children in the camp eligible to come to Britain through family reunification, France has so far fallen short of setting out provisions to rehouse or resettle hundreds of other lone child refugees. During a partial demolition of the makeshift homes in February this year, aid workers estimated that as many as 100 children simply disappeared.

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.