One man's fight to clear name 'ruined' by racist bent copper who framed him 45 years ago

The policeman who put away Winston Trew, DS Derek Ridgewell, was later jailed for seven years for theft.

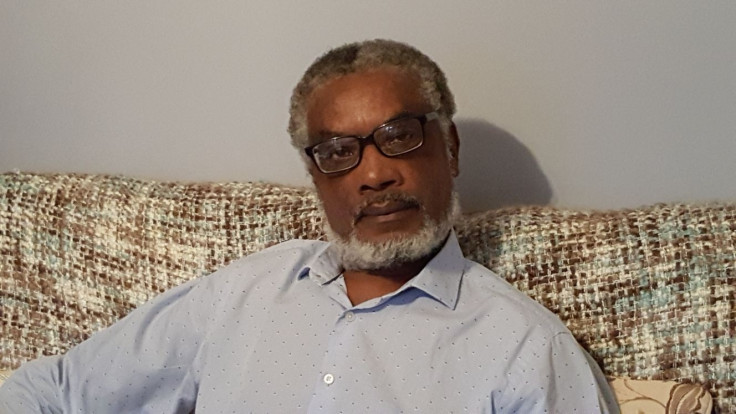

Winston Trew has been fighting to clear his name for 45 years after an innocent late-night Tube journey home with three friends inadvertently plunged him into the cauldron of British race relations in the 1970s.

Trew, along with three other young black men, were confronted by plain-clothed policemen in the Oval London Underground booking office and accused of pickpocketing. A fight broke out and by the end of a sharp March night in 1972 the youths were charged with police assault and theft.

The case is controversial because the British Transport policeman who led the arrest, DS Derek Ridgewell, was later convicted of theft himself. (IBTimes UK is aware of at least one other alleged miscarriage of justice involving Ridgewell, more on that later).

Unbeknown to Trew, his arresting officer was at the centre of the collapse of a series of cases in the 1970s where young black men were violently arrested and sent to prison after signing forced confessions for muggings on the London Underground.

Violence on the Tube was a high-profile public concern at the time. Prevailing attitudes towards ethnic groups such as Caribbeans and the Irish, who had come to the UK in large numbers, were less than enlightened.

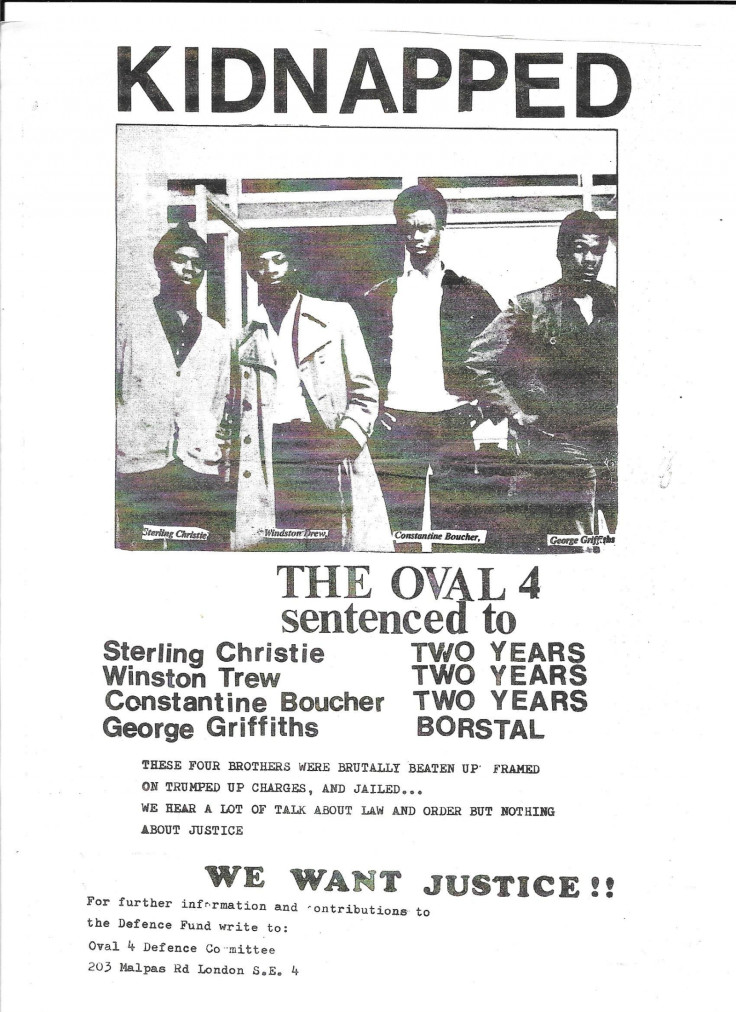

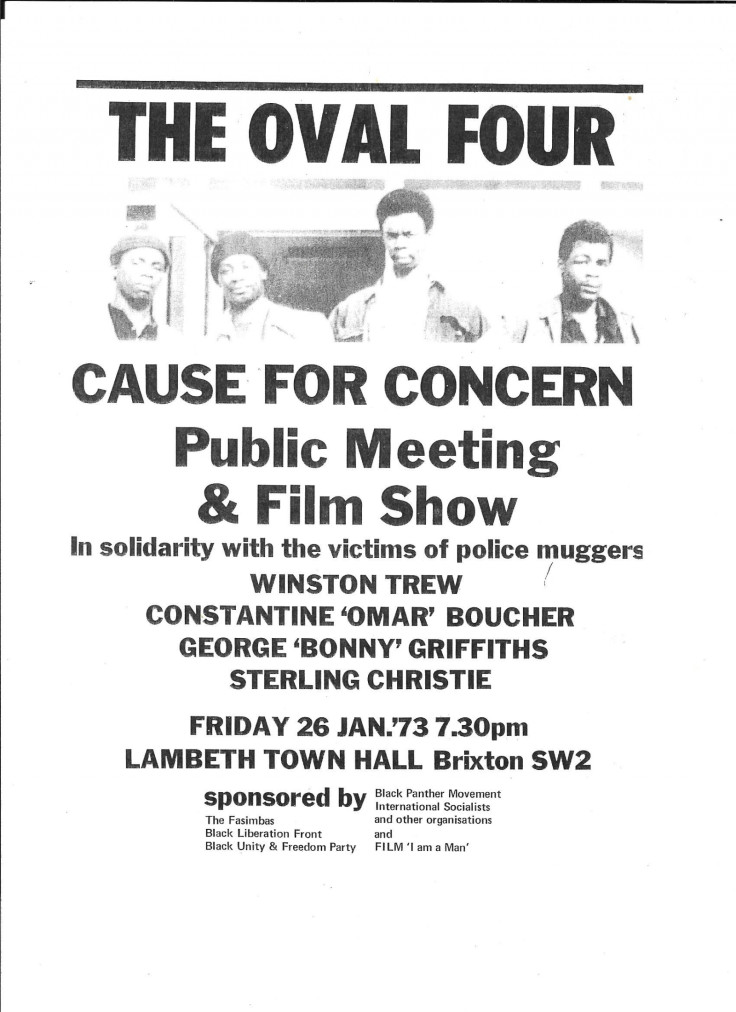

A series of cases Ridgewell led became cause célèbres. In accordance with the time, the groups of men were given monikers such as the Oval Four, the Stockwell Six, the Waterloo Four and the Tottenham Court Road Two. All these cases either fell apart or saw sentences which would be heavily reduced on appeal in 14 dramatic months that ended in the summer of 1973.

Trew, who emigrated from Jamaica with his family when he was six, would become forever linked with Ridgewell, a dark, complex figure, on a late March evening in 1972.

The 21-year-old and his friends were making their way back from north London and were coming out of the Tube at the Oval. They were approached by a number of plain-clothed officers on the up escalator and cornered in the booking hall.

"For a second I thought it was just white men trying to have a laugh," said Trew, now 67, a retired sociology lecturer, who still lives in south London.

"They said they were police, but they refused to show us any ID. They said they had seen us trying to pick pockets and had stolen a lady's handbag. We told them that was rubbish. We had nothing on us. There was a bit of pushing a shoving, then a fight broke out."

I wasn't afraid of anybody

Trew and his three friends were black power activists at the time. That night they had been coming back from a political meeting in Harringay, north London. They all helped run Saturday morning schools for black youngsters, attended political rallies, all had marital arts training.

"I was young and angry then. I wasn't afraid of anybody," said Trew.

But the men were overpowered and brought to Kennington police station. They were separated and beaten until they signed false confessions to scores of thefts and muggings.

During the night one of the officers pulled down a book of local unsolved crimes and set about getting Trew to admit to them. But he only 'confessed' to crimes committed at around ten on a Thursday morning. This was the time he signed on for unemployment benefit at Peckham Labour Exchange. This alibi would help him later in court.

Community groups raised around £4,000 (over £48,000 today) for the 23-day trial at the Old Bailey in October 1972 for the quartet who had acquired the soubriquet the Oval Four. The men in the dock were Constantine Boucher, 25, Sterling Christie, 22, George Griffiths, 19, and Trew.

The jury did not convict them on the multitude of crimes the youths had admitted to on their confessions, partly because Trew could prove he was in the labour exchange at the time and not miles across south London committing muggings.

But they were convicted on the evidence of what the police said they saw on the night their paths crossed.

They were found guilty of theft and police assault and given two years in prison, with the youngest, Griffiths, serving the same sentence in a borstal.

The 'guilty' pronouncement is still writ large on Trew's memory. His mother collapsed in the packed public gallery as the judge gave his verdict, while the mother of another one of the men screamed. Pandemonium broke out between their supporters and police guards.

"When I heard the sentence I could feel myself shrinking in the dock", remembers Trew. "I thought 'There's no way out of this. I'm finished with.'"

The stress of the trial had worn down Trew's immune system and the next thing he remembers is waking up in the hospital wing of Wormwood Scrubs prison, west London, exhausted and suffering from flu.

Life in Wormwood Scrubs

Trew and the two older men were held in Wormwood Scrubs for four months, before being transferred to Eastchurch prison on the Isle of Sheppey in Kent.

Trew said although he was sent books and money by supporters "most of the prison day is just spent with the thoughts [of the conviction] in your head. And that is lonely."

However, the three men were treated as minor celebrities by other black prisoners, and even by a number of white inmates, simply because they had stood up to the police.

The four men immediately appealed. But during an eight-month wait for a fresh court date something happened that Trew said would prove "fundamental" to his case.

Ridgewell continued to push for robbery convictions, and in May 1973 a case he led came to trial, involving the arrest for robbery of two black men at Tottenham Court Road station, central London.

But during their trial it emerged that the two men from Rhodesia (now Zimbabwe) were both Jesuits studying at Plater College, Oxford University, with no previous convictions.

There had been an altercation with police, but the students said they thought they were about to be mugged on the Tube, an issue they had ironically read so much about in British newspapers at the time.

Judge halts trial

Judge Gwyn Morris halted the trial saying: "I find it terrible that here in London people using public transport should be pounced upon by police officers without a word that they are police officers.

"One of these men was set upon by police without a single word being uttered about being arrested. Only after he had been grabbed, manhandled and wrested to the ground at the top of a long escalator was he told he was being arrested and that they were policemen in plain clothes."

Trew's barristers argued that the collapse of Tottenham Court Road Two case showed there was a clear pattern of violent arrests and false confessions linked to cases led by Ridgewell's team at his appeal two months later in July. This made all such convictions he was involved with unsafe, his lawyers argued.

But while the Court of Appeal dismissed the confessions as unsafe it was still happy to rely on the evidence of the police on the night. This was that they allegedly 'saw' the men attempt to pick pockets and that they were attacked by the quartet.

But the court did cut the Oval Four's sentences in half to one year, and as they had almost served two thirds of that, or eight months, they were released the next day.

Trew said his release was not the homecoming he had hoped for.

"I came back home. I was free, but I was still a criminal," he said. "I was still convicted of one count of police assault and two counts of theft. I didn't come out of my house for days."

Haunted dreams

The strain of the jail term had taken its toll on his first marriage. A few months after his release, his wife left him, taking their two children to the US.

He said: "I was haunted by what happened to me. I used to dream about it most nights for years."

However, Trew began to rebuild his life. He worked in social and community work for a decade, before spending 13 years as a lecturer at a London university. He married his second wife in 1984, and they have two children.

In 2004 Trew began a book about his case, hoping to make sense of what happened. It took him five years of research and heavy use of the Freedom of Information Act to complete before self-publishing it a year later in 2010.

In the book, Black for a Cause ... Not just Because, Trew found that Ridgewell joined the British Transport Police as a constable at 19 in 1964. Before that he spent short spells as a clerk and working in a pub in south east London, where his mother was an assistant manager.

He moved to Bromley, Kent, with his family when he was seven, after being raised in Glasgow, the eldest of two boys.

But after almost 18 months in the British Transport Police he decided he wanted to see the world and advance his prospects.

He moved to become a police officer in Rhodesia in October 1965. But his timing could not have been worse.

Move to Rhodesia

A month later Rhodesian Prime Minister Ian Smith declared a Unilateral Declaration of Independence from the UK, as Britain and its colony were deadlocked on negotiations over black majority rule. British Prime Minister Harold Wilson declared Smith's move illegal and imposed sanctions.

By the end of November Ridgewell was back in Kent, and gave an interview to the local paper saying he had left the southern African country a few weeks into his year-long contract with the Rhodesian police because he did not like their "military-style" training and their rough treatment of black people.

Ridgewell rejoined the British Transport Police by the end of 1965, and by January 1972 he had risen to become Detective Sergeant in the newly formed robbery squad, aimed at combating Tube crime.

Trew says the pressure Ridgewell was under to achieve high arrest and conviction rates, led him to scoop up handfuls of black men on the underground and beat confessions out of them.

After their cases began to fall apart the British Transport Police's robbery squad was disbanded after only 18 months and Ridgewell was quietly moved to probe thefts at the railway's Bricklayer's Arms Goods Depot in south London in 1976.

But during his investigation he was turned by a couple of career criminals and began to split the proceeds from stolen parcels. During his 15 months on the case thefts went up at the depot rather than down. The British Transport Police secretly put a second team on the case who broke open the ring.

At Ridgewell's Old Bailey trial the jury heard around 11 van-loads of parcels had disappeared during his time on the case at an estimated cost of £367,000 (£1.4m at today's prices). He was sentenced to seven years in prison for conspiracy to steal in 1980.

I just went bent

Staff at Ford prison made a report on Ridgewell and asked why he had decided to work with criminals. His only reply was: "I just went bent."

But just two years into his sentence Ridgewell died of a heart attack, after being found collapsed in a toilet cubicle in his landing early on New Year's Eve morning in 1982, aged 37.

On the night before Ridgewell died an inquest heard that the former police officer had lost three stone over the last months of his life, ending up at 10 stone. He had also been to the prison doctor complaining of diahorrea and vomiting three times over the previous six months.

A prisoner told the inquest he had spoken to Ridgewell on the night before he died and the ex-policeman spoke of his features "becoming drawn", which was a concern ahead of a family visit a few days away.

Not surprisingly Trew did not shed a tear when he heard about Ridgewell's death.

"I despise him. He has ruined my life. But at the same time, I didn't know the type of person I was until I was trapped in that police cell with him and his colleagues overnight. That has become part of who I am."

Does he feel betrayed by the country he left the small eastern Jamaican town of Seaforth for in 1956, or did he just run into a rogue cop?

"My parents brought me here for an education and a better life. I got that, but it was a rollercoaster. I had to work for it. I am proud of who I have become."

Stealing mailbags

The British Transport Police said: "In the last 40 years, there has been a considerable change in how British Transport Police identifies and investigates police misconduct. Our dedicated and impartial professional standards department meticulously investigate all allegations of misconduct and ensures that any wrongdoing is identified and dealt with.

"Gross misconduct hearings are brought before an independent panel and held in public. Likewise, where necessary, cases are referred to the Independent Police Complaints Commission who conducts their own investigations."

But over forty years later Ridgewell continues to cast a shadow over people he crossed paths with.

During his time working on the south London depot thefts, the corrupt copper still liked to artificially boost his arrest and conviction figures.

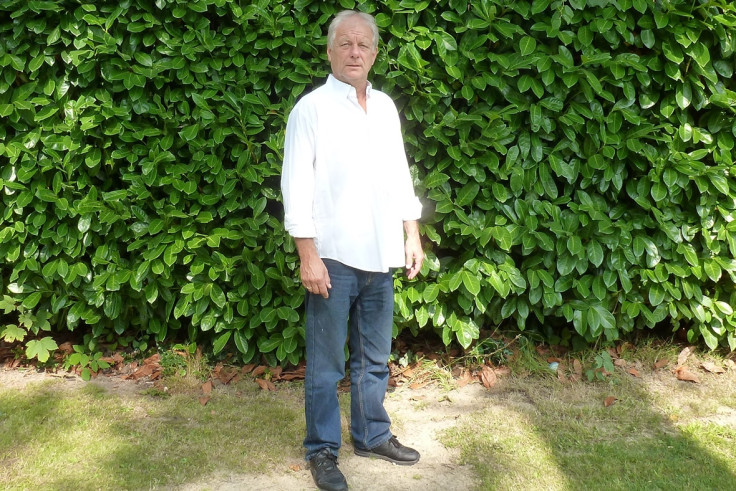

In 1976, then 21-year-old Stephen Simmons and two friends were convicted of stealing mailbags after being approached by Ridgewell and his team in Clapham, south London. No goods were ever found, but Ridgewell claimed in court that Simmons had said the goods were stashed elsewhere.

Simmons was sent to Hollesley Bay borstal in Suffolk at 21 and served eight months of a two-year sentence.

But now Simmons' case is due to come before the Court of Appeal over coming months, after a referral by all three sitting judges at the Criminal Cases Review Commission. The 62-year-old, who runs an audio and phone equipment business, is now one step away from clearing his name of a 41-year old conviction.

Fighting demons

In August, Simmons told IBTimes UK: "Ridgewell ruined three lives for no reason and many more I am sure. But if British Transport Police had prosecuted him or even forced him out of law enforcement, this would not have happened to me or others who were unlucky enough to come across him."

Trew added: "I am waiting on the Simmons case. If he overturns his conviction, then that will be a clear sign that so much of what Ridgewell did was unsafe. If he wins his appeal, I will set about appealing my convictions."

Simmons, who now lives in Dorking in Surrey, and Trew have never met. But Trew has sent him papers that might help his case.

Winston Trew and Stephen Simmons. Two men from different backgrounds, but both have spent more than half their lifetimes fighting to clear their names.

All down to the actions of the same bent copper.

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.