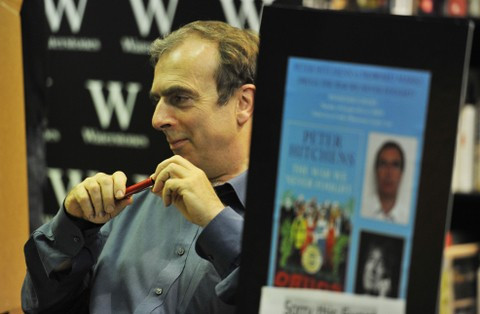

Peter Hitchens Interview Transcript in Full

William Dove: Who is this book aimed at?

Peter Hitchens: Simon Jenkins mostly. Because as someone for whom I have a lot of respect as a commentator, who's influential, rightly perceived as an original intelligent mind and usually takes a great deal of trouble to ascertain the facts and on this he seems to have got it completely wrong and I feel that it's time that intelligent people debated this matter with a bit more knowledge.

It's obvious that something is wrong with the British drug laws but the conventional wisdom view, of which he is one of the most prominent supporters - is that the laws are too tough, that they are not working and that we should just get rid of the whole thing.

There is another explanation that is we have laws which exist only in theory but not in practice. Anyone who knows much about our legal explanation can see that's quite a likely explanation and in this case it turns out to be true.

So it's aimed at him and a lot of commentators and in fact a whole phalanxes of opinion formers, politicians, media people, civil servants and police officers who have been barking up the wrong tree on drugs for years and I got so sick of it that I thought the only thing I could do in all responsibility was to provide them with the arguments to prove that they were wrong.

WD: In the book you describe him as "the most influential lobbyist for drug decriminalisation" in Britain.

PH: I think he is so influential because he is so widely read and people have such a high opinion of him. He's not tied to any lobby; he's not pursuing anybody's agenda. He's an independent figure and people of that kind have very powerful effects on national debate.

WD: He's more influential than for example Paul McCartney, who also takes an important role in your book?

PH: Paul McCartney has been very effective but I think that his era is over. I think Paul McCartney's role in the initial establishment of the Wotton Report as the kind of report that it was , the great Times advertisement of 1967 had an enormous impact but I think that now we're in a different stage. Paul McCartney is a figure of the past.

WD: You seem to be a bit nicer to Roy Jenkins in this book - he usually comes off quite badly in your books.

PH: I've no personal animosity towards Roy Jenkins. He's an intelligent and thoughtful person - he's just an opponent and I disagree with him. I think that his objectives were wrong and I think he helped to create a much more unpleasant society than would otherwise have been. It's nothing personal.

WD: In the book you make very limited claims about the dangers of cannabis.

PH: You have to because any claims have to be based on demonstrable facts and it is very difficult to demonstrate hard objective facts on the link between cannabis and mental illness. There are several reasons for this that I set out in the book.

First of all there is correlation - to move from correlation to causation is extremely difficult - one of the reasons it so difficult is how does one definite mental illness objectively?

One of the most interesting developments of the last few months has been the report which has linked cannabis use among young people with declining intelligence and that's because it's generally accepted that there is an objective measure of intelligence and one can therefore say that this actually happened.

The only measure of mental illness generally is not objective it's the American Psychiatric Association's diagnostic and statistical manual, which is now about to go into its 5<sup>th edition and changes all the time.

I don't use terms myself - although I quote people who do - like psychosis and schizophrenia because I don't know what they mean. They have no objective definition and you can't therefore say with any certainty by seriously repeatable objective tests that somebody has psychosis or schizophrenia in the same way that you can say that someone has cancer of the lung.

WD: You don't think these limited claims weaken any of your arguments?

PH: No because I think it's blazingly true that cannabis has an effect on people's mental health and I think that there is so much so called anecdotal evidence. My friend Patrick Cockburn, the great foreign correspondent, whose son Henry became very seriously mentally ill after cannabis use in his early school years is amazed since he wrote this fantastic book Henry's Demons - which is one of the most moving and gruelling accounts of this - how many people of his generation and mine came and said after he's revealed his own tragedy something similar has happened to me. It's very common; it's a fact of life among parents of my generation that they either have children or friends of their children who heavily use cannabis who have subsequently become seriously irrevocably mentally ill.

It's not possible it seems to me to dismiss that as anecdotal when it's so common. But how one would set about doing the science to establish a causal link I don't know. I will tell you this - when Sir Richard Doll, as he then was, and his colleagues in the initial tobacco research got in their first major results that showed a correlation between smoking and lung cancer every single one of them gave up smoking that night.

These are scientists - they know that although correlation isn't necessarily causation it does not necessarily not cause it. They could see there was something there. I believe there are people who still argue the causation between smoking and lung cancer is yet to be proved. And they are welcome to this - you can be that rigorous if you want to but it is one of those instances in which the best is the enemy of the good. You have to recognise at some stage that there is enough common sense evidence to suggest that there is something going on here.

What would be surprising about a drug that impacts very powerfully upon the human being having an effect on the mental health of the person who uses it? What would be a surprise about that?

WD: Recently on your blog you posted a lot of anecdotes from former cannabis users and their relatives - I'm guessing you've been sent a lot more that have not been published?

PH: No, those are the ones which were sent to me in the aftermath of my publishing. I'm sure there are many others which have not been sent to me as either people don't know that I want them, they prefer not to send them to me or they're afraid that their own personal lives will be invaded or possibly they just think it's too painful. I don't doubt these things exist, they go on all the time.

There's no state body, there's no academic body, there's no commercial body with a powerful interest in pursuing this. If you think about it who would it be? Research doesn't just happen in a vacuum. It happens because somebody wants to pay for it.

WD: Those in favour of drugs will often quote the JS Mill "do no harm" type principle - but you say that's a misreading of Mill?

PH: Well it's not true. Even Mills arguments on alcohol in "On Liberty" are obligatory. He doesn't really get to grips with it. In the end he comes up apparently assuming that alcohol's only effect is criminal behaviour outside the home of the individual - he comes up with a type of prototype ASBO, which is a far from libertarian solution to the problem.

He doesn't address what is actually the main effect of drugs, which is a contradiction of the harm principle - which is on the immediate family of the drug user.

WD: It's not a victimless crime then?

PH: Absolutely not. The victims tend to be the person closest to the user. Those actually less able to employ the criminal or civil law to restrain his behaviour once the drugs have kicked in. Deterrence is a much more effective and actually freedom loving approach. OK you're free to do this if you want but if you do it we'll punish you rather than confecting ASBOs or treating it as an illness making people who take drugs permanently in some way obliged to or forced to register with or be subject to the ministrations of the state which is what we seem to be heading towards.

WD: How would you fight the war on drugs?

PH: I would deter people from using them.

WD: With what kind of sentences?

PH: Well it doesn't really matter but it has to be something credible. I would take as my example the efforts to stamp out drunken driving in the '60s which was a combination of serious penalties with where rapidly and systematically applied during the initial period backed up by a powerful state advertising campaign warning people of the consequences.

I think you might undoubtedly find that a small number of individuals would get caught which is always a pity. I'd much rather people wouldn't take drugs in the first place but they'd have to be the sacrifices for the general good that I'd be prepared to make. I don't think you'd have a queue of martyrs in Belmarsh for the sake of the great cause of cannabis.

Fewer people will use it and the main people would be those who currently face enormous pressure, particularly at school from their school friends to try drugs that could ruin their lives. If you said to someone now, "I can't take that because the police might catch me", everybody would laugh - they know the police aren't interested and nothing will happen to you.

If people can honestly say, "If I get involved with this stuff I could lose my career - I could never be able to travel to the United States for the rest of my life" - and it was credible - then it would be a really good argument.

A lot of the purpose of law is to provide people under pressure from lawbreakers not to join them.

That's how the drink drive laws were. There was enormous social pressure in the saloon bar with the kind of "Come on Josh have another one - police will never catch you nothing will happen, have another drink!" That stopped at once when the breathalyser came in. Someone under pressure could say "Don't be stupid I don't want to lose my license" end of argument. It's a force that enables people to resist peer pressure to do something stupid and wrong. It's a very valuable function of law.

WD: You blame the police for lobbying in favour of a softer approach on drugs?

PH: Senior police officers who have actually stood up and lobbied against the drug laws seem to me to be in breach of their oaths of office. They swear to uphold the law. It is absolutely not their job to make public pleas against the law they are sworn to uphold. They have debarred themselves from that.

Once they've left the police they can because they cease to be sworn officers. But while they are serving police officers as far as I'm concerned it's a breach of the oath to campaign against the laws you are sworn to uphold. Quite simple. Morally wrong - probably legally wrong as well - I'm amazed they get away with it.

WD: You mention Aldous Huxley in the book and the idea that freedom to take drugs, sexual freedoms etc. actually go against freedom of speech and political freedoms?

PH: It's not so much that they go against it. I was surprised when this began to happen because it never occurred to me that people would think this - that people compare the freedom to take drugs with freedom of speech and assembly.

I'm not a libertarian, I'm a Christian - my principles are based on the Christian religion not on some fantasy that liberty in all things is possible or justified.

I am in general in favour of a government heavily restricted where people are largely free to do what they like and I tend to think of myself as being on the side of liberty.

I can't see why the freedom to stupefy yourself and to become therefore a passive acquiescent serf in mental terms is comparable with freedom of speech, thought or assembly and I still don't.

I think Huxley's point is that the Soma society he warns of is one in which people learn to love their own servitude is the absolute opposite of what someone who loves liberty would desire and I do think that confronted with a society you dislike if the response is to fog your brain with chemicals rather than campaign for its reform then you are retreating. I can't think of anybody in authority being displeased by the idea of passive, compliant, acquiescent subjects.

In Brave New World which oddly enough has become less well known than it's less prophetic rival 1984 one of the most important means of controlling the population is Soma the happiness drug - which is used, as I mention in the book, to quell a riot.

It could not be more clearly stated but for those who could not see it Huxley in his preface and in his speech actually is quite specific. He was afraid of a society where we would be drugged into servitude and loving that servitude and I think that is a big problem with this subject and one of the reasons why the most arrant rubbish can be stated by politicians at party conferences and why our country can be systematically and ceaselessly misgoverned and they get away with it, is that so many of the people who ought to be alert and campaigning against it have taken the route of happiness drugs.

WD: Through the book you go through large chunks of the police, the media and the political class are in favour of legalising or being soft on drugs - why despite this huge influence are so many people still against it?

PH: I don't know how large it is. I think the unending propaganda of the drug lobby is diminishing the majority all the time. In the book I recount how when I was making a television programme about David Cameron and someone set up for me to meet a bunch of Tory activists and as it turned out they were all members of the Monday Club and we were sitting in this pub in Windsor and I was not finding them terribly communicative or useful and it was never used in the programme. But what was astonishing was that every single one of them, supposedly hard core reactionaries, was in favour of the decriminalisation of cannabis.

WD: Do you think there is still a majority against decriminalisation?

PH: I don't know - I wouldn't bank on it. Majorities have no interest to me, a majority can often be wrong. There's still enough of a group of voters, probably people over 60 who are feared by the political parties for nobody openly to risk legalisation of drugs. There's also the problem of international treaty obligations which mean they can eviscerate the law but they can't actually repeal it.

WD: One argument used by those in favour of legalisation is that by keeping drugs illegal thousands of people are being killed in Latin America in a real war on drugs

PH: I don't understand the logical progression. What contributes to the deaths are the selfish greed, stupidity and self-indulgence of people in western countries who take and buy these drugs and so stimulate the immoral trade which leads to those deaths.

Everyone who takes these drugs is helping to kill poor people in Mexico and Columbia and they should be ashamed of it. There's no connection between the illegalities of a drug it's the fact that stupid, self-indulgent immoral people in the west behave in this fashion.

WD: The methadone programme comes in for some criticism in your book. It sounds like it should be a real health scandal?

PH: It should be scandal. Lots of things should be scandals. It's amazing how many things are not scandals that should.

WD: I was surprised to read in the book that in Edinburgh more people die are believed to die from methadone than from heroin use - I'm guessing there are no figures to indicate if this is true in the rest of the country?

PH: Edinburgh is not that dissimilar. Even Russell Brand - bless him - is against the methadone programme. Even he can see through it.

WD: There was that semi-famous encounter between the two of you on Newsnight.

PH: Which we didn't actually discuss that aspect of it as Stephanie Flanders chose to put the question a different way but if I'd been offered the opportunity I would have said Russell Brand is right about methadone. He's wrong about rehab but he's right about methadone.

Actually I think a hamster could see the methadone programme is stupid. I really don't think it takes much of an effort. It is also effectively George Osborne mugging the population on behalf of heroin users.

WD: What would happen if cannabis was made legal officially and not just in practice?

PH: It's possible for it to be commercially marketed. Meet the big cigarette companies, meet the big alcohol companies, meet the big pharmaceuticals. These people are good at what they do - let them market cannabis.

A lot of health authorities won't proscribe it but there is a legal version of THC and then imagine if that could be marketed at Boots and in Waitrose?

WD: You make the point that the arguments in favour of cannabis are the same as those who said smoking was safe. Where cannabis legalised in the near future do you think 50 years from now people will look back at cannabis in the way we look at smoking now?

PH: I'm certain of it. But why does one have to spend 50 years of stuffing people into the locked wards of mental hospitals who would never have needed to go there. Why bother to read a crystal ball when you can read the book?

Now if we legalised it many people would be needlessly damaged. Why take the risk?

WD: Where did you get the idea for you amusing indexes?

PH: This is the third one of these I've done. I was offered the services of an indexer but I thought I'd do it myself and I just found it an entertaining way of doing it. I think in some ways the index is the best chapter in some of these books.

Why should indexes be dull?

WD: Your next book will be about the Second World War I believe?

PH: Yes the national religion. [It's called] The Phoney Victory. We all think we won when we lost.

WD: What's the progress so far?

PH: It's very difficult to start on one book when you are still involved in the publication of another and it's not wholly out of your system

WD: You'll be expanding on what you've called the "Churchill Cult"?

PH: Partly. Each of these books arises from something I touched on in a previous book and I feel there is more to it than I can deal with in this book. For example the crime book [The Abolition of Liberty] which I wrote ten years ago came out of the Abolition of Britain when I realised that in my brief treatment of law and order I simply hadn't begun to touch it.

WD: That book was aimed at the British left

PH: Any book is aimed at the British left because the British left control more or less what is discussed, how its discussed and how its legislated. If you can't influence them then you might as well go home.

WD: Have any of your books influenced them?

PH: None of them. They are uninfluenceable because they've stopped thinking. They stopped thinking long ago they've become locked in like the Catholic Church before the Reformation. They can't see any faults within their circle.

WD: The result of too much cannabis?

PH: I wouldn't be surprised. The main thing that is to blame is that they themselves for the most part live fat, metropolitan, bourgeois lives that are not disturbed by the consequences of their ideas. If they had to live in the nastier parts of Middlesbrough they'd change their minds in ten minutes but they don't so they don't.

WD: These nastier parts are spreading to the nicer parts now you say?

PH: Oh they are - also the people who live in them are not necessarily staying confined in them. If you use public transport late at night you can run into it. The left avoid it by travelling by car. I'm a great public transport user myself.

WD: Apart from in their songs how do pop/rock musicians lobby for drugs?

PH: In the cases that I mentioned the Beatles were very specific. All four of them signed the Times advertisement in 1967 and all four of them used their MBEs to do so. That was absolutely explicit but the other is in the way that they live.

A lot of people look on the rock star's life as enviable and one to be purposely pursued.

It's partly because as Bernard Levin pointed out many years ago most people clocked onto the fact that you are never going to become rich by working.

The national lottery and football are the delusions of the poor. The rock star lifestyle goes further up the scale. It's common, people do look up to these people as examples and they think there is something heroic about it. They look at Keith Richard as I still call him - he was Keith Richard when I were a lad - he got rid of the S and then readopted it later on. A lot of people look on him as a kind of heroic figure

WD: That might not be the case for someone like Amy Winehouse though?

PH: I don't know about that - you may say that but what's it about? There is this kind of mythology of Janis Joplins and Amy Winehouses and earlier than that - the great jazz singers and piano players that there is something somehow enviable about this sort of on the edge rackety lifestyle. I think a lot of people romanticise it and think of it as legitimating probably their own more cautious fooling around with sex, drugs and rock and roll.

I think if you have a lot of prominent very rich people who live on the edge then people will envy that. As John Berger pointed out years and years ago the key to advertising is making people envy themselves as they would be if they bought the product.

People think what if I became one of those. They envy themselves as they would be so that influences their choices in life. It makes it easier as well. If big rich successful admired people are doing something then less successful people will add a little to their lives by copying them. We know this.

It's like the hideous phrase "role model" which I try to avoid.

WD: Speaking of role model's if anyone comes out well in this book its James Callaghan isn't it?

PH: In my view he should probably have resigned rather than pilot the bill through. He put up a bit of a fight but ultimately Jim Callaghan was an ambitious politician who wanted to be prime minister and I think he realised that resigning over this at this stage wouldn't get him anywhere.

Also it's unclear and I don't know if it ever will be clear, as to whether by leaking stories to the Sunday Mirror he was trying to pose as an opponent of drug legalisation or whether he was genuinely trying to prevent it. I don't know.

Whether he even realised exactly how much of a failure, people often don't until years after, it had been I don't know. I suspect from the way he behaved in the debate when Reginald Maudling came back with his own old bill I suspect that he had very strong regrets.

WD: Why are so few public figures against drugs? You mention only Angela Watkinson opposed liberalisation on the Home Affairs Committee (on which David Cameron also sat).

PH: She did occasionally have some support but it wasn't reliable there was another guy called Humphrey Malins who sometimes voted with her but in terms of holding out to the bitter end she was the only one who did.

WD: In the broader world of media, politics etc why are so few people publicly anti-drugs?

PH: Because conventional wisdom is very powerful, because politicians are ambitious and subservient to the whips and also because this generation is corrupted by drugs. It was corrupted by drugs in the 60s and then the 70s. Sex, drugs and rock and roll are not linked by accident there is a general acceptance of licence in your personal life which became common in that period that includes drugs and people who accept that licentiousness (and most people have) are not going to argue against it.

There is also the curious reverse blackmail. Say you as a politician developed a conviction that drugs legalisation was a bad idea but you had yourself taken cannabis when you were at university what would happen?

WD: It's quite obvious

PH: Quite. So unless you have considerable courage to say yes I did use it and it was a stupid and wrong thing to do which I regret profoundly you then face the possibility of being outed by your old college friends. It's something that happened to Dan Quayle, although whether it's true or not I don't know, but people definitely emerged and said he had been [taking drugs].

Most people want a quiet life but it's interesting that when politicians do come out it's usually to say ha-ha I used drugs in the past just like everybody else and they don't then say anything about regretting it. It's one thing people really hate to do.

People ask me did you take drugs I say yes, although my drug use was so pitifully small it barely deserves a mention, and I then say it was one of the stupidest things I've ever done and I regret it profoundly and it hurts to say that. It's embarrassing and you then have to tell your children, you then have to tell friends who've known you in your adult life and are surprised by it. It makes you feel bad and people don't like to do that.

So that's one of the reasons why, because of this reverse blackmail.

It's much easier to keep quiet, run with the crowd - don't make yourself conspicuous. Conventional wisdom, political fashion, account for an awful lot of what people say in public which in many cases is quite different from what they think in private.

WD: Anything further you'd like to say?

PH: Read the book. It won't make any difference it's a lost cause but all the good causes are lost. I have to work on the assumption (I may be wrong) but I've seen no evidence whatsoever that anybody's paying any attention

WD: An exercise in moral courage you said recently.

PH: That would be self-praise wouldn't it?

WD: You said it while arguing for the death penalty I believe. [Here: https://hitchensblog.mailonsunday.co.uk/2012/10/my-first-reply-to-martin-narey-.html]

PH: I hope I didn't say courage. It's just an exercise in free speech - although that is increasingly constrained by law in this country although people don't realise that. Free speech is mainly constrained by self-censorship. Conventional wisdom is always wrong - you can bank on that. For people like me who are considered to be lunatic fringe elements it actually makes it easier for other people who are not on the fringe to start saying a bit later on after we've gone. I'm the first wave I go up over the top and get machine gunned down and the second wave might have a slightly better chance.

WD: The book was a little different to what I expected. It was more of a history of cannabis rather than a fiery attack on cannabis.

PH: I am a historian. Had I not the great good fortune to become a journalist, history is the trade I would have followed. I might now be a junior lecturer in history at Nottingham University rather than doing what I'm doing.

The trouble is because I'm not I can write the book and as you rightly point out it is a historical book but it will be met with geysers of slime or total ignoral by the people I most want to read it.

"The Rage Against God" did a bit [of publicity] but the book that really got me cut off the list was the anti-Cameron book. I was punished by the Conservative Party

WD: How, apart from not reviewing your book?

PH: There are other ways which I won't go into because it would be hard to prove though I'm quite certain of it that one or two things occurred.

WD: Over lunch?

PH: I'm sure lunches or dinners were involved in ensuring that they did occur. But the moment you say that people start saying you're a conspiracy theorist, your paranoid. Conspiracys happen and as you rightly point out they are called lunch and as for being paranoid. Just because you're paranoid doesn't mean they are not trying to get you.

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.