Poetic injustice: The plight of persecuted women poets

The body of Susana Chávez Castillo was discovered just over four years ago in the city of Ciudad Juárez in northern Mexico. Found with a bag over her head, the 36-year-old prominent poet and women's rights advocate has been strangled, and in a chillingly symbolic act by her killers, her hand had been cut off. Castillo had gained recognition for her campaigns, both in person and in her writing, against the wave of killings and sexual violence against women in the Juárez area since 1993. One of her most famous poems, Sangre Nuestra – Our Blood – was written from the perspective of a victim.

Most people regard poetry as a quiet, introspective activity. In some places, poets can safely rely on the protection of freedom of expression to paint literary pictures of society and its pitfalls. And in the majority of western democracies, official censorship of poetry is residual – intended primarily to shield children from profanity. Yet when poetry and politics collide, poets with a talent for parody and creating poems that sniff out hypocrisy, double-think and inequality are at risk of being censored, vilified, imprisoned, tortured, exiled or murdered – for practicing the not-so-gentle art.

Throughout the course of the investigation into the murder of Castillo, Mexican authorities denied that her death was related in any way to her activism and her poetry. It was eventually concluded that she was killed by three teenage boys she had met while out drinking, yet the stance of local rights defenders has remained the same: Castillo was killed because her poetry highlighted an injustice that nobody wanted to hear.

Short, poisonous snake

It is rare that perpetrators are brought to justice, and in the vast majority of murders of writers and journalists, impunity reigns.

"In societies where the role of women in public life is restricted, women poets often face harassment, or worse, purely for the independent expression of their thoughts in verse," Cathal Sheerin, a researcher and campaigner for PEN International, tells IBTimes UK ahead of World Poetry Day.

"But the risk these poets run is often double. Their poetry might provoke the ire of the prevailing patriarchy, but it is frequently the other work that these women so often engage in – the promotion of literacy among women or women's rights in general – that so disturbs those who hold power, and which is so often punished by harassment, violence or imprisonment."

The plight of female poets is recorded in history. Russian modernist poet Anna Akhmatova's work, characterised by its clear leading female voice and emotional restraint, meditated on the Great Terror under Stalin; when under pressure from the regime, she chose to remain in Russia to act as witness to the atrocities around her. When her son Lev was arrested in 1938, Akhmatova burned her notebooks of poems and from then on, memorised everything she wrote to recite in private readings to trusted friends.

Yet in 2015, female poets are still hounded for creating verse that goes against accepted societal values. In Afghanistan, Pashtun poetry has long been a form of rebellion for women. Landai – meaning "short, poisonous snake" in Pashto – are also two-line folk poems, many of which address forced marriage with bitter humour. Of the 15 million women in Afghanistan, only five out of 100 graduate from high school and three out of four are forcibly married by 16. Violence is common. In 2005, the celebrated young poet Nadia Anjuman, from Herat University, was killed after a severe beating from her husband. She was 25.

The largest women's literary society in Afghanistan is called Mirman Baheer. In Kabul, women are generally free to attend functions but in the rural provinces, where around 300 members live, they are forced to attend in secret. Such groups have been around for a long time but during the Taliban rule, were hidden. In 1996, an underground educational circle called the Golden Needle Sewing School, organised by Herat University, was formed by women writers of the Herat Literary Circle. Pretending to gather together to sew, women would discuss, write and read literature that mirrored the discrimination they faced.

Political persecution

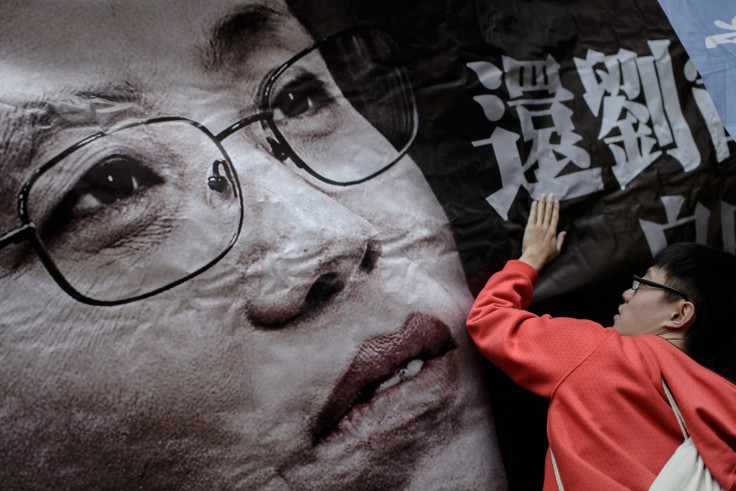

More often than not, the combination of women's rights and political ideology form the reasons for persecution. Liu Xia, a founding member of the Independent Chinese PEN centre, has been under house arrest in Beijing since October 2010 – when her husband, writer and activist Dr Liu Xiaobo, was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize for his work calling for the end of communist single-party rule. Journalists from the Associated Press and a handful of activists have managed to slip past the guards outside her compound in the past, but have been able to see her for only a few minutes. She is reported to be depressed and suffering from ill physical health.

There is a widening space and enthusiasm for literary creativity in human rights, but it comes at a cost. San San Nweh, a noted writer and one of the first women in Burma to receive journalism training in the country, was imprisoned between 1994 and 2001 by the Burmese military junta for her "anti-government intentions". Since 1974, she has published a dozen novels, over 500 short stories and around 100 poems, but was arrested for "publishing information harmful to the state" in 1994. In 2001, she and fellow journalist Win Tin were jointly awarded the World Association of Newspapers' Golden Pen of Freedom Award.

But what is it about poets that those in positions of authoritarian power fear? It is because poets are the antithesis of a repressive, totalitarian spirit; and in this medium of expression women have the power to tell the truth about what they see? For the truth – whether it is about rape or the degradation of forced marriage – is unpalatable and complicated. Reading fiction helps develop empathy and social understanding, and helps us stand up to prejudice and discrimination.

"If, by reading... we are enabled to step, for one moment, into another person's shoes, to get right under their skin, then that is already a great achievement," Archbishop Desmond Tutu once said. "Through empathy we overcome prejudice, develop tolerance and ultimately understand love. Stories can bring understanding, healing, reconciliation and unity."

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.