The Gay Planet and Queering the Industry: It's Time for Video Games to Come Out

Following the huge backlash directed at Bioware for it's decision to include a 'gay planet' in it's Star Wars: The Old Republic game, Ed Smith asks if the time is right for video games to come out.

Gay, bisexual and transgender people need better representation in videogames - this has to happen. Basic decency dictates that everyone, regardless of race, gender and sexuality should be treated equally, and video games, by continually pushing against that, are starting to look out of touch and creatively stale.

For decades now they've been made by straight white men for straight white men, and if the plummeting sales figures from 2012's fourth-quarter tell us anything, it's that the heterosexual guy market is reaching saturation. If videogames are going to thrive, not just as a diverse, intelligent art form, but also as an entertainment industry, they need to get queer.

How? In the words of Anna Anthropy, a transgender game designer from Oakland, "by hiring more f***ing queer people to work in the industry for a start."

"I think game publishers are being cowards in terms of how they believe gay and trans characters would be received," says Anthropy. "There's really no excuse for that kind of commercial cowardice. Although those people exist, the people who will always react negatively to a gay character in a videogame - who might even make an e-petition or some dumb thing - I don't think they're the only voice. There's a growing audience who would be interested in seeing games move past that."

And now more than ever, that audience is finding its voice. In blogs like this one and this one; in the hugely negative reaction to BioWare's bewildering 'gay planet' announcement (more on that later) and in the work of developers like Anthropy, gay and transgender game audiences are gradually getting their message heard.

The internet, smartphones and digital distribution hubs are giving gay artists and critics a platform, at last. It's the beginning of a new movement which Jose Arroyo, lecturer at the University of Warwick and author of Queering the Folklore, says was heralded in the film world by the rise of VHS:

"After the beginning of the Gay Liberation Movement, which dates from the Stonewall riots of 1969, there was a call for representation. Characters slowly began to appear.

"The beginnings of VHS created the market, because if you could sell X amount of copies on video you could make your money back. VHS permitted these kinds of independent cinema; films with small budgets, aimed at particular niche markets, could make their money back."

Gay Interest

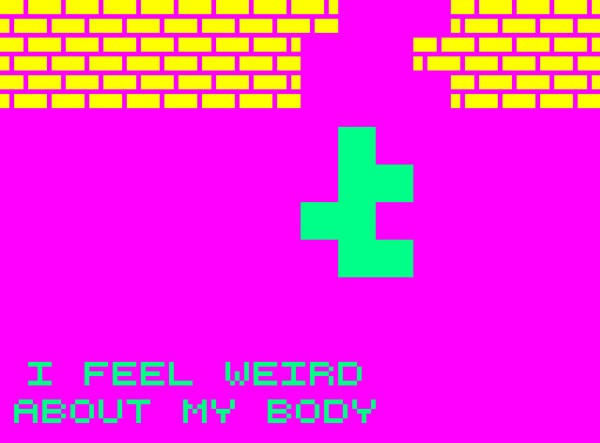

The Gay Interest films of the 1980s and early nineties (Gus Van Sant's My Own Private Idaho, Derek Jarman's Caravaggio) were sparsely funded, non-professional efforts targeted at viewers Hollywood dare not speak to. They're mirrored in videogaming by independent works like Dys4ia, Anthropy's game about gender frustration, and Coming Out on Top, a gay dating sim that recently passed its Kickstarter target.

Like the cinema of the late 1980s, if equal and intelligent representations of gayness are going to appear in the mainstream, they need to come from outside the industry first:

"It seems to me that the thing that's most transforming games is the number of queer people who are making games outside of the industry," says Anthropy. "We're reaching a point where non-professionals can make games and distribute them on the internet. What I see as a really transformative force is queer people making their own games."

So, what are publishers afraid of? Is it gamers? Because if it is, they shouldn't be scared. It's precisely the same petulant frat boys that threaten to rape and kill Anita Sarkeesian who are the first to whinge that games are unoriginal. The collective sigh on internet forums that follows a new CoD game ought to indicate to publishers that their target market of young men is growing tired, and that some new - queer - ideas might bring with them a fresh sack of profit. Anthropy seems to think so:

"The industry's idea of who they're selling to is to a large extent shaping what they make. They've driven gay people out in a way that can't make financial sense. It's bewildering to think how that's even profitable.

"I played a game the other day about a bisexual girl and her coming out to a lesbian community, and I think that's an infinitely more interesting story than playing a gay character in Mass Effect. I feel like the more queer people are actively engaged in telling these stories, the more the industry is going to have to evolve to keep up with them."

"If people in AAA studios were a little braver," she continues "they would find people who would welcome gay characters and new experiences with open arms."

Jose Arroyo believes a market exists for queer games, too. A specialist on Pedro Almodovar, he understands that, even in the most craven industry of mainstream cinema, gay audiences are out there:

"If there are gay videogame developers who want to do something for a particular audience, they should just do it because it will find a market," he explains. "I think changes could come from financial strategies rather than from a Utopian ideal of social justice. I think the social justice stuff has made people aware that this market exists, but the driving force is money. And there is a market to be addressed; there is a pink pound.

"And in the light of TV shows like The New Normal, and Obama's inauguration speech, I think it would be foolhardy not to engage with it on some level. If the president is seeking to directly address gay equality, then it would be very odd if entertainment industries, which are always particularly vulnerable, didn't take that on board somehow."

Gay Planet

But if the market is there to be addressed, it needs to be addressed respectfully. Coming back round to Makeb, The Old Republic's 'gay planet', BioWare recently insulted all of its gay players by insisting that if they want to be homosexual in-game, they need to remain in a segregated area and pay for the privilege to do so.

A "troubling" move says Anthropy, totally at odds with what she aims to do with her own work:

"The games I make, a big part of them is my own identity - representing my experience as a queer, trans, TV person. There are a couple of reasons why I want to do that. First is that the sheltered, typical game player might encounter these games and be forced to reconcile the fact that not only do queer people exist, but they're also involved in the creation of games.

"But the other reason is so that other queer and trans people might feel a little safer in what is traditionally a culture which is hostile and alienating. The thing that's really worrying [about Makeb] is the idea of voluntary queer exile. I find that troubling, that there's only one corner in this game universe where gay people are allowed to exist."

In a very tangible sense, Makeb is at odds with videogames' coming out. Where the creative and written work of Anthropy and others seeks to integrate and include gay people in computer games, Makeb separates them. That this might be considered applaudable is disconcerting.

However, in reference to the 'queering' of cinema before the 1980s, Jose Arroyo says that mainstream games, starved of overtly gay representation though they may be, could still appeal to homosexual and transsexual audiences:

"Queering referred to a process where gay people as an interpretive community would read things into films that other people couldn't see. So, there were queer readings of The Wizard Oz and The Lucy Show and things like that.

"It's very possible that gay audiences don't need gay representation to enjoy videogames. They can take certain representations that already exist and can have things that aren't necessarily gay that speak to them already. The way cinema spoke to gay audiences at a particular time existed before openly gay criticism."

Though it's the perfunctory relationships in Mass Effect which normally receive praise, Anna Anthropy finds more value in Saints Row 2:

"I feel like in mainstream games, gay people are token...Queerness as it's represented in videogames is really superficial.

"But one game that really impressed with me how it let the player handle gendering their character was Saints Row 2. When you're making or clothing your character, you can mix and match all these differently gendered things - you can give your character tits, or a moustache, or a masculine or feminine voice. That seems to me a lot closer to the way that we actually gender ourselves. A lot of people told me that that was the first game where they were able to make a character that resembled their body shape."

Coming Out

For all creative purposes, it feels like games are ready to be gay. Since the 1990s, AAA material has revolved mostly around heterosexual power fantasies - shooting zombies, racing cars and playing soldier. But as the industry lurches into the next console generation, what will hopefully come is a little deviation. In the way that Gay Interest eventually seeped into Hollywood with films like Philadelphia and Beautiful Thing, so too could independent queer developers find mainstream representation.

And if publishers are still timid about representing gayness in their products, they need only look at the declining sales figures (even the invincible Black Ops took a dive last year) to see that consumers are weary of the same old straightness. That 'pink pound' that Jose Arroyo talks about is out there to be claimed, and although monetary gain mightn't be the purest motivation for big companies to gender bend, it's at least something they might understand:

"I think we forget how oppressive the situation was not that long ago," concludes Arroyo. "I'm not that old, but I remember the first gay bars that I went to, where you would have police come in with machine-guns to just hang out there and terrorise you. It's very recent, what we're talking about, so we do need to be aware of it in a social justice kind of way. But on the other hand, I think if you're addressing these audiences, it can make you a lot of money."

Anna Anthropy is more forthright. In a recent post on her Auntie Pixelante blog, she wrote:

"Queer games are important. The more people we allow to make games - the more voices speaking - the more games begin to look like you, and me, and all of us."

We already live on a gay planet. It's time for games to come out.

BioWare was asked to speak on this topic but refused to comment.

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.