The race to 5G is nothing but a PR fantasy

Connected cars, superfast phones, and human augmentation – this was the 5G vision coming out of Intel's Developer Forum in San Francisco last week (18-20 August). But as much I'm sure that all of these technologies will flourish in the coming years, I don't think they're going to be part of anything that we'll call 5G.

The trouble is that 5G is a theoretical solution for a problem that's yet to be defined. The telecoms industry needs to create another "G" to keep investors interested. Rather than addressing the industry's real deficiencies, such as the global digital divide, the industry is trying to think of ways that adaptations of its own technology can "disrupt" other less efficient industries.

To achieve that goal, the tightly knit club of global equipment vendors are collaborating in a series of international standardisation and intergovernmental fora. When vendors claim a new 5G breakthrough, they are probably talking of a research project with researchers from several different companies. But on its own terms, I doubt the real disruptive technologies will be developed before impatient marketeers slap the "5G" label on something quite different.

What is 5G?

To understand 5G you have to get an idea of the narrative the telecoms industry has created. According to this, a G (generation) is what happens every ten years – starting in the 1980s: 1G was analogue voice, 2G is digital voice, 3G is mobile internet access, and 4G is mobile video.

Intel's vision – as revealed last week - aligns with a broadly shared vision within the industry. This vision includes improvements to the current mobile broadband offering such as higher speeds and greater capacity on the networks. More interestingly, it also includes other characteristics such as low latency, ultra-reliability, and low cost chipsets.

Latency is the delay present in the network, such as the one you can sometimes perceive in applications like Skype. If this can be brought down to levels that are brushing up against the limitations of the fundamental laws of physics, then interacting through a wireless network would effectively be equivalent to direct physical interaction.

If your car's mobile connection has a low enough latency, then it may be just as safe to drive your children home from school remotely, as it is from behind the wheel. Equally, a surgeon could treat patients from hundreds of miles away.

Bringing the cost of wireless connections down could also allow the mass deployment of wireless chips in to every conceivable item. This is why Ericsson often talks of the "Internet of Everything". In this scenario, machines are not only receiving instructions from human, but are talking amongst themselves. If every car had a 5G connection, then your car could learn about road conditions by receiving information from other cars.

Who is working on 5G?

Equipment vendors are leading research on 5G. Sometimes this research spills out of in-house labs and in to funding university projects. For example, Nokia, Samsung, and others are pushing the boundaries on what type of radio spectrum you can use in collaboration with NYU.

Mobile operators tend to think in the shorter terms than vendors, but are still looking at 5G. Japanese operator NTT Docomo in particular is active on 5G and is pursuing trials in Tokyo with both Western vendors such as Ericsson and Nokia, as well as Eastern ones such as NEC and Samsung.

On the public sector side, the European Commission has pledged to spend €700m on research into 5G in the hope that European industry will invest a further €3.5bn. The EC is also working with the South Korean government to further develop 5G. The Chinese government is researching 5G through the IMT-2020 Promotion Group.

IMT-2020 is the term used by the International Telecommunications Union (ITU) to describe what the rest of the world calls 5G. The ITU is the UN agency that manages claims on the use of radio spectrum and satellite orbital slots, and also does developmental and standardization work.

The 5G process

4G is nominally known by the ITU as IMT-Advanced but if you look up these standards, you will find that your download speed is supposed to be 1 gigabit per second. But six years after the world's first "4G" launch in Scandinavia, your 4G phone in likely to be downloading at speeds around 70 times slower than that (the average UK 4G download speed is 14.7 megabits per second).

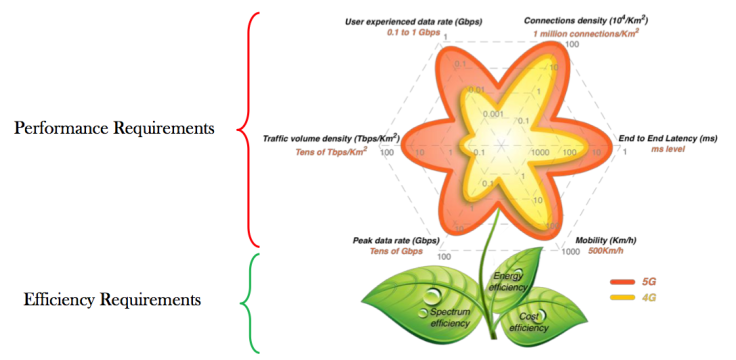

4G is standardised by an organisation called the 3Rd Generation Partnership Project (3GPP), which brings together the equipment makers and service providers behind your mobile broadband service. 3GPP will ultimately be the body that standardises 5G, but first it needs to agree on its requirements. An example of these is shown in the diagram below, which was made by the IMT- 2020 Promotion Group for an event in London last Autumn.

Requirements will be discussed in detail at a meeting in Phoenix, Arizona, in September. Agreed requirements will be adopted in December. After that, 3GPP's members will coordinate on the hard engineering job of making 5G. The 5G standard itself will be complete by the end of 2019, a couple of months before the ITU will hold a meeting defining IMT-2020

Will 5G just be 4G?

Or at least, this is the official timetable. Tokyo is hosting the Summer Olympics in 2020 and Pyeong Chang in South Korea is hosting the Winter Olympics in 2018. Both of these hyper-connected countries are likely to want to use the events to showcase some form of "5G" network. Ominously, the Winter Olympic's motto is "Passion. Connected".

To accommodate this, 3GPP is considering an early drop of some 5G standards. This is more likely to contain further enhancements to 4G than a new air-interface (the way your mobile phone talks to its base station). But that leaves operators in other parts of the world with a problem. If your competitors in the Far East are deploying "5G" then the pressure builds on you to deliver your own version of 5G. After all, a 1gbps "5G" network is impressive when compared to a 14.7 mbps 4G network.

Perhaps then, the truly transformational ideas may well fall out of the 5G umbrella. The sad truth is that instead of a standard, 5G will be whatever product operators have at hand to sell us consumers in 5 years time. 5G exists for the same reason that Jurassic World, Fast & Furious 7, and Mission: Impossible – Rogue Nation exist, because someone somewhere made a lot of money out of the prequels.

The truly new applications may well instead end up transforming the world's industrial production and distribution, rather than your type of phone. After all, a robot doesn't care what kind of G it has.

Toby is a journalist at the radio spectrum management newsletter PolicyTracker, and the co-author of Understanding Spectrum Liberalisation which will be published on 31 August, 2015.

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.