Rate hikes: a double-edged sword for central banks

While higher rates aim to tame runaway inflation by slowing economic activity, they can cause a recession if borrowing costs become too steep for businesses and individuals.

Central banks worldwide are using aggressive interest rate hikes to lasso galloping inflation, at the risk of pulling down the global economy with it.

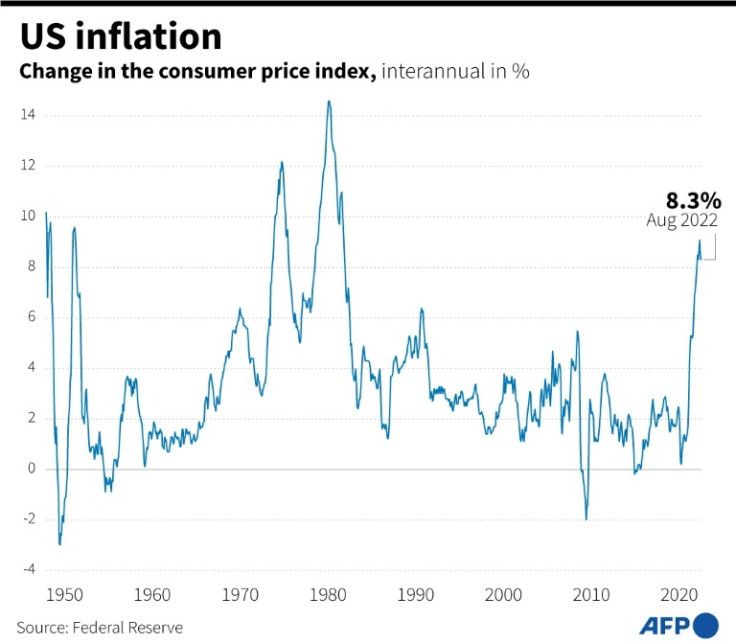

The US Federal Reserve and its counterparts in Europe and most emerging economies have been raising rates this year as consumer prices have soared to decades-high levels.

While higher rates aim to tame runaway inflation by slowing economic activity, they can cause a recession if borrowing costs become too steep for businesses and individuals.

"It reminds me what used to happen in the Middle Ages: bloodletting," Nobel laureate economist Joseph Stiglitz told AFP, referring to the belief at the time that patients could be cured from illnesses by making them bleed.

"When they let out the blood, the patient didn't recover, usually, unless a miracle happened. And so they let out more blood and the patient got sicker and sicker," Stiglitz said.

"I am afraid that central banks will do the same thing now," he warned.

The Federal Reserve will announce its latest monetary policy decision on Wednesday, with investors fearing that after two straight rate increases of 0.75 percentage points, the bank could go for a full point this time.

The Bank of England and its peers in South Africa, Sweden and Switzerland are also expected to continue to tighten their monetary policies at their own meetings this week.

Consumer prices began to rise due to bottlenecks in supply chains as companies struggled to keep up with a pick-up in demand after economies began to emerge from Covid lockdowns.

After repeatedly describing inflation as "transitory" last year, the Federal Reserve and the European Central Bank changed their tune this year as Russia's invasion of Ukraine caused energy and food prices to soar.

Central banks have since raised hikes in an almost synchronised way, raising concerns that their late and aggressive reactions could now do more harm than good.

"Did the economy really need this to slow down?" said Eric Dor, director of economic studies at the IESEG school of management in France.

"Inflation itself caused activity to slow down," Dor said. "Households are losing their purchasing power, wages increases are lower than the inflation rate and (inflation) put a brake on consumption."

ECB President Christine Lagarde acknowledged the possible hit to the economy last week.

"Will it cause a little loss of growth? It's possible," she said Friday at a conference in Paris. "It is a risk that we have to take after weighing it well."

Earlier this month, US Treasury Secretary Janet Yellen said there is "certainly a risk" of an economic downturn.

But she noted the US job market is "exceptionally strong" with nearly two vacancies for every worker looking for a job.

The United States is still haunted by the spectre of inflation that lasted for almost a decade in the 1970s and 1980s.

A World Bank report released last week said a worldwide slowdown accompanied by tighter monetary policies could trigger a global recession next year, with sharp declines in emerging and developing countries in particular.

While economists debate whether the cure for inflation might be worse than the disease, some disagree over the reasons behind the soaring prices.

Stiglitz said demand is not the cause.

"Central banks around the world are pretending or acting as if it was demand that created inflation," he said, noting that higher rates will neither produce more energy nor food or help ease the global supply chain crisis.

"Using a recipe for the wrong diagnosis is getting the wrong prescription," he said, adding that higher rates will raise the cost of making the investments needed to relieve the bottlenecks and raise rents in the United States.

© Copyright AFP 2024. All rights reserved.