Tiny mysterious 'fluorescent lantern' species discovered living on sea snails in Red Sea

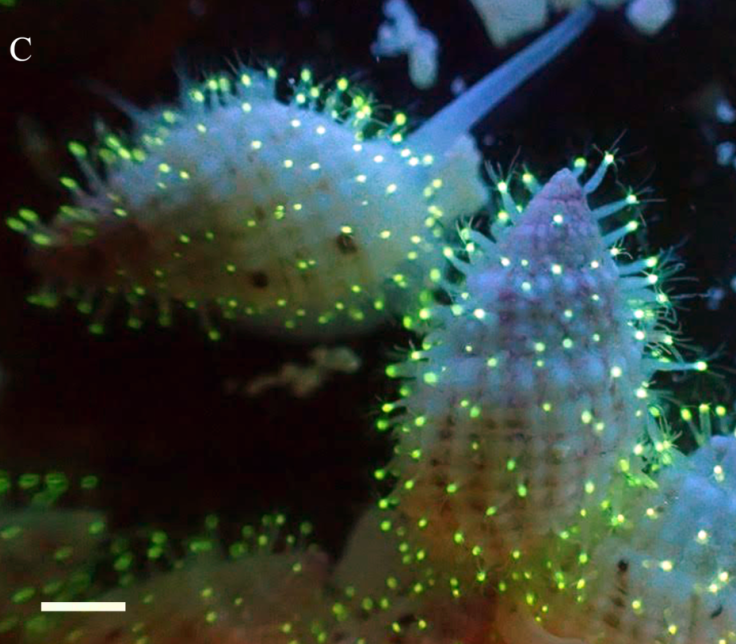

A new species described as "fluorescent lanterns" has been discovered in the Red Sea. The tiny creatures, from the genus Cytaeis, were found attached to 3cm-long sea snails, with up to 126 decorating just one snail.

The green lanterns stick to a species of sea snail known as Nassarius margaritifer, and point outwards to create a Christmas tree-like effect. The discovery was reported in the journal PLOS ONE.

The researchers from the Lomonosov Moscow State University say that the species is a distant relative of the marine hydra genus – tiny organisms that float through tropical freshwater regions. The difference is that these newly found creatures – a type of hydroid – are symbiotic, and live on other organisms; in this case, the miniature sea snails.

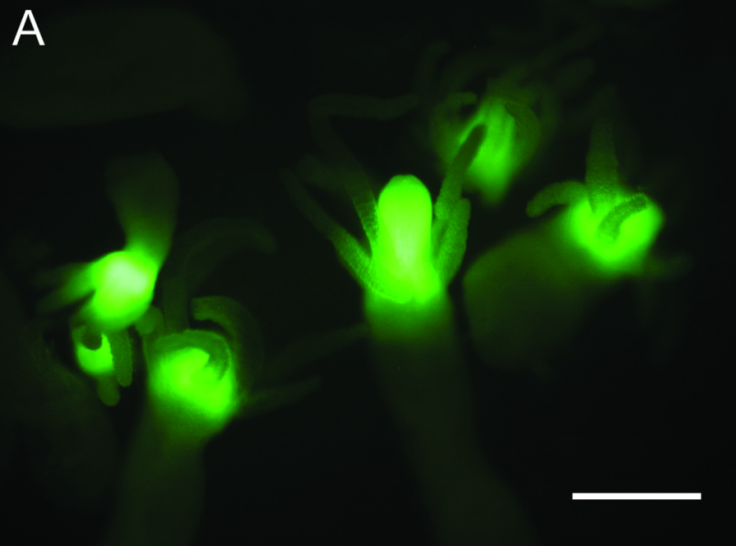

"Sea hydroids, unlike hydrae, are often found in colonies and can branch off tiny jellyfish," said Vyacheslav Ivanenko, one of the researchers on the study. "The unusual green glow of these hydrozoas – whose body length reaches 1.5 mm – was revealed in the peristomal area of the body [around the mouth]."

Biologists working on the study found the little lanterns on the south-east coast of the Farasan Islands, Saudi Arabia. They ventured out on a night dive in 2014, using UV-light with yellow filters to guide their way deep underwater.

They discovered the bright green glow on the sandy bottom, and collected 32 specimens of the sea snail which had the luminous species stuck to it. DNA analysis on the creatures allowed the researchers to compare them to other known similar species, to try and identify what these specimens actually were.

Ivanenko explained: "The comparison of the fluorescence of hydroid found in the Red Sea to those of other hydroids of the same genus allowed to reveal the species-specific fluorescence of morphologically indistinguishable species of Cytaeis."

While the role of the green glow has not yet been confirmed, the biologists believe it may have a part to play in attracting prey. Seeing as the light is close to the species' mouth, potential food may move toward it – like a fly to a lamp. When it is just close enough, the Cytaeis species can claim its dinner.

The next step of research is to analyse the effects of moon and sunlight on the fluorescence. The researchers say that the hydroids need light to power their glow, but more research needs to be carried out on how the fluorescence changes depending on whether it is daytime or night-time.

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.