Revealed: The UK councils using property guardians despite 'exploitation' fears

Most councils using property guardian companies have no policy, despite legal and ethical question marks.

Councils across the UK are allowing so-called "property guardian" companies to use taxpayer-owned buildings for free – and in some cases are even paying them – an investigation by IBTimes UK reveals.

The vast majority of councils, which house at least 1,000 property guardians, currently have no formal policy in place, despite myriad ethical and legal issues surrounding what have been dubbed the "zero-hours contracts of housing".

"Councils are very nervous about this legally," said Sian Berry, a Green member of the London Assembly and the party's 2016 candidate for the city's mayoralty. Berry wants to see councils take the lead on developing a set of minimum standards for guardians to safeguard their rights and interests.

A property guardian is someone who occupies an otherwise vacant property on behalf of the owner to deter squatters. In the past few years, this has turned into an industry in which property guardian companies have sprung up to take advantage of owners desperate to keep squatters out of vacant buildings. Such firms get guardians to sign license agreements to explicitly state they are not tenants, and therefore have fewer rights under housing laws.

Freedom of Information requests by IBTimes UK show that at least 67 councils said they use property guardians to secure vacant buildings, including former care homes, social housing estates due for regeneration and sports centres. Many councils refused to give certain details, citing exemptions under the law relating to commercial sensitivity.

At least 20 councils receive no income from the guardian companies, which charge guardians a "licence fee" to live in a property – a de facto rent. Some councils actually pay the guardian companies they use: Guildford gives Camelot Europe £495.72 a month and Bexley pays the same company £281.67. Both are paying to place guardians in one property.

"The council's policy on safeguarding vacant property is to use guardians where this is considered to be the most cost-effective method of ensuring that the property is not vandalised or squatted in," said Bexley council.

Guildford council said it "employed Camelot on an ad-hoc basis to meet a specific and urgent requirement to secure a habitable but dilapidated farmhouse and cottage where the cost of security guards would have been unjustifiable and where various planning and environmental issues were correctly predicted to delay any redevelopment or sale of the site or buildings".

Previous research by Berry showed that Enfield council paid guardian companies £16,648 in the first half of 2016 to run two properties. Islington shelled out £6,540 for three. Many councils refuse to release details about their financial relationship with guardian companies, which are potentially generating a six-figure sum from local authorities across the country.

There are at least 1,073 guardians living in council-owned buildings across the UK, though some councils could or would not say how many there were. Most councils could not produce the licence agreements between the guardian companies and the guardians because they did not hold copies, while many admitted to having no policy in place on using guardians.

"I think all councils should have a policy on it and I think they all need to try and liaise together and co-ordinate," said Rex Duis, a guardian and campaigner behind Property Guardians UK. "For guardians, as well as the agencies, and all the councils, it means that everybody is on the same page. Everyone has a clear document that sets out rights and responsibilities. No-one has unrealistic expectations."

The Local Government Association, a body representing hundreds of councils across the country, did not respond to a request for comment.

Property guardians also live in vacant buildings, which are often not residential, such as empty offices or community centres. Guardians are not tenants. The licence agreements they sign before living in the properties mean they are "licencees", and so in theory easier to remove.

Their licence fee is usually cheaper than local rents for ordinary homes. Guardian companies act as property managers and handle the lettings, charging various fees to the guardians, which is how they make money. Property guardianship remains a legal grey area and campaigners want clarity.

Houses of multiple occupation

Councils are responsible for enforcing standards such as fire regulations and health and safety rules for property, both commercial and residential. Guardian companies also say they carry out safety checks of buildings.

But guardian-occupied properties often avoid having the licenced status of House in Multiple Occupation (HMO), where several unrelated tenants live in a home owned by a landlord, because they are not technically tenanted buildings. HMOs are subject to strict housing standards, policed by local councils.

Berry said she has pushed the mayor of London to seek clarification from the Department for Communities and Local Government (DCLG) on whether all properties with multiple guardians should count as HMOs, and is waiting for a response. "It would be really good if we can get them all under the HMO regulations, which at least have health and safety standards," she said.

The DCLG did not respond to a request for comment. "This area needs to be looked at across the industry and that includes the whole rental market," said Ad Hoc managing director Simon Finneran. "We ensure we adhere to standard regulations, albeit there are a number of variations by region."

Under one detailed proposed charter for the guardianship industry, put forward by Property Guardians UK, guardian companies should adhere to HMO rules regardless, "including provision of one toilet and one shower per five people". Camden council has made Camelot obtain an HMO licence in the past, according to documents seen by IBTimes UK.

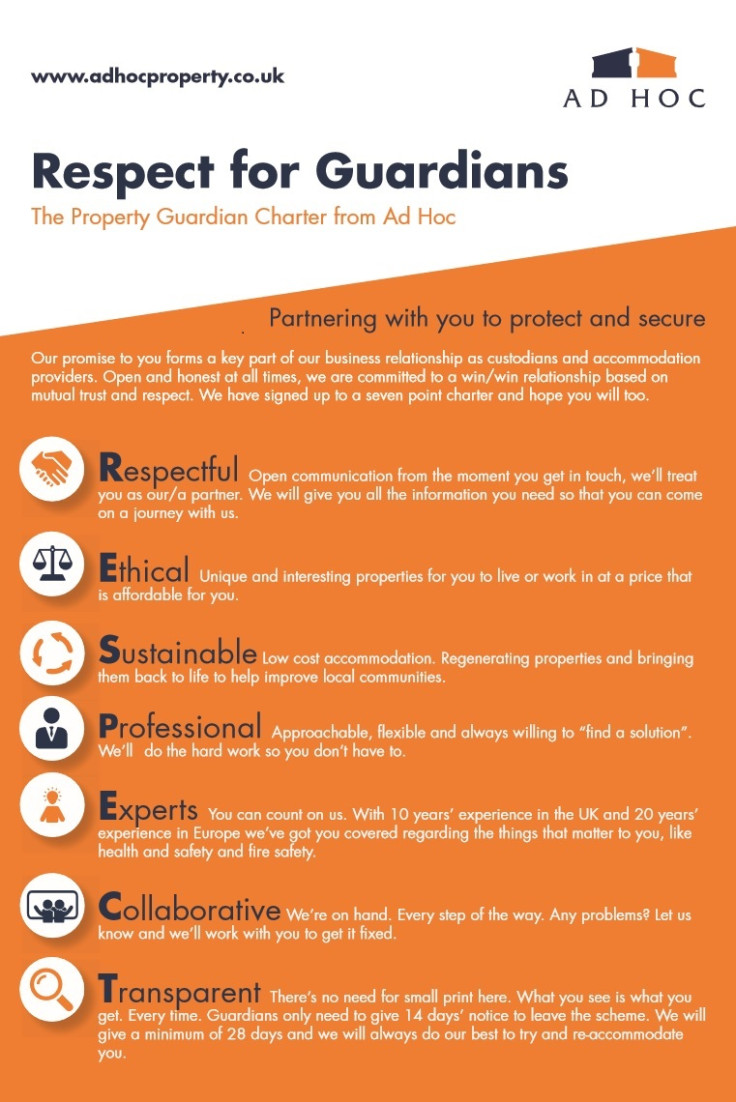

Ad Hoc has already introduced its own seven-point "Respect for Guardians" charter, which includes commitments to being "ethical" and "respectful" — and believes it could be a model for the whole sector.

"We make sure that we have continuous dialogue with guardians (and property owners) – and are pleased with the reception that our Guardian Charter has received from across the country," said Finneran.

"This is the first step, we believe, in rolling out these commitments across responsible members of our industry. Importantly, local authorities need to ensure they carry out due diligence on who they do business with and in that way also help to ensure standards are met by the industry."

Other property guardian companies also take on aspects of self-regulation.

"Where we have five guardians in a property, we should comply [with the HMO system]," said Doug Edwards, managing director of VPS Guardian Services. Edwards said that while it is not the law that guardian properties must automatically fall under HMO legislation, VPS chooses to adhere to those standards.

As the property owners, however, it is the councils who are at risk from litigation under the Occupiers Liability Act and Defective Premises Act if anything serious were to go wrong for the guardians because of the buildings they are occupying, said Giles Peaker, a partner at Anthony Gold Solicitors. This exposes authorities to the potential for substantial damages payouts. Many of the properties were never intended to be homes.

"To be fair, councils are usually better at making sure the properties are up to a reasonably inhabitable standard than some private companies might be, but the whole situation is now getting a little complicated," said Peaker, who has handled a number of cases relating to property guardianship.

The Eviction Act

Another legal pitfall for councils is the issue of eviction. If a guardianship was what is called an "exclusive occupation", because the landlord does not live in the property, it would count as an ordinary tenancy, giving tenants the right to shut out their landlords, forcing them to secure an eviction order from the court.

It is common in guardianship licence agreements to explicitly state that there is not exclusive occupation of the property. Croydon council was among the few to produce a copy of one of these agreements.

"You will not get a right to exclusive occupation of any part of the living space," says the licence agreement from Camelot. "The House of Lords has held that this sort of sharing agreement does not create a tenancy [...] You will, therefore, have to vacate the building as soon as the agreement is terminated."

Residential occupiers of property are entitled under eviction law to be given 28 days notice if they have to vacate it. Some guardian companies are known to give much shorter notice than this because they do not believe they are subject to the legislation, as the occupants are licensees.

But Peaker, who is chair of the Housing Law Practitioners Association, says he has brought a number of eviction claims against guardian companies and succeeded every time in securing an out of court settlement. This shows, he said, that the Eviction Act applies to guardians.

"I haven't found anybody with a viable argument to the contrary and every landlord and tenant lawyer I know agrees with the analysis; the protection of the Eviction Act applies, therefore a minimum of four weeks notice and they can only be evicted by a valid court order, which means possession proceedings," Peaker said.

If guardians in council properties dig in their heels when the time comes to leave, the council faces going to the courts for an eviction order to remove them. "I am pretty confident that at least some of the guardian companies are not making that clear," Peaker said.

He added that some councils include in their contracts with guardian companies that the firms are the ones responsible for launching these proceedings, including the costs involved. "If the council was smart - and I know some of them are - they would have effectively a penalty built into their agreement to cover that," he said.

Finneran of Ad Hoc said he agrees that "all elements apply" of the Eviction Act to property guardians. Edwards of VPS also said the act applies to guardians and that the company always gives a minimum of 28 days notice, sometimes more.

'Guardians are treated fairly'

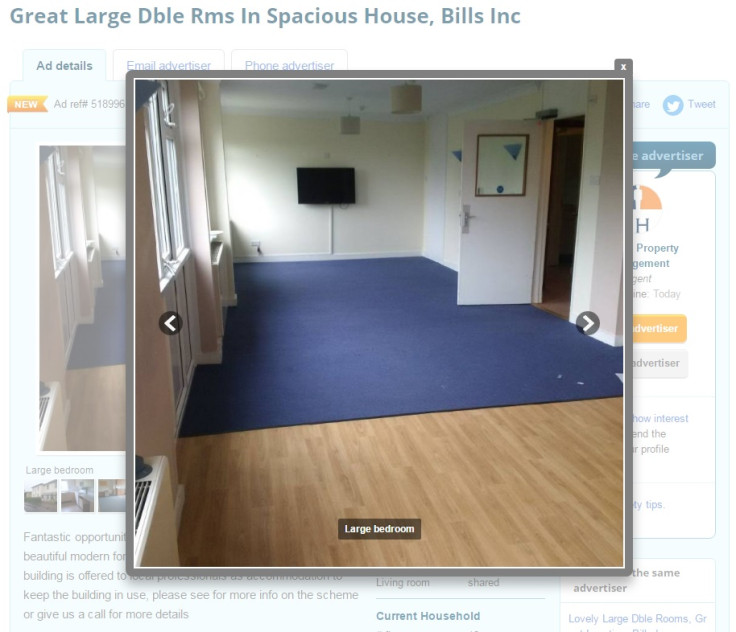

In one example unearthed by IBTimes UK, Southampton City Council contracts the company Ad Hoc to put guardians in a former care home to keep the building secure. The listing by Ad Hoc for the building, which can accommodate 10 guardians, demands a monthly rent of £299 – with all bills included – plus a deposit of £350 and a registration fee of £130.

Therefore in rent alone Ad Hoc can generate potential revenue of £2,990 a month — from which Southampton council will receive nothing. Southampton does not pay Ad Hoc anything either, and the council said it "is using [Ad Hoc] to avoid the council having to spend a considerable amount of money to keep the property secure. It is only intended to be a short-term interim measure".

Waltham Forest council in London made the largest income from guardian companies, bringing in £5,363 a month in total from Blue Door Property Guardians, Dex Property Management, Camelot and VPS, who manage 64 guardians across six properties. The council said it "makes use of guardian companies where appropriate". It seeks proposals from multiple bidders for the contracts to manage the guardianships, and the "most economically advantageous proposal is accepted". It does not pay the guardian companies.

Camden council in London was the biggest user of guardians, with 183 of them in 177 properties. The vast majority of these are securing homes on estates earmarked for regeneration, living in the properties in the time between the old tenants moving out and the construction work starting.

Camden would not say how much it receives from VPS, the contractor it uses, but confirmed it is paid for every property occupied by a guardian. It does not pay VPS. "We also pick up all the costs for making each and every building safe and habitable," Edwards of VPS said. "With Camden, every property is inspected before a guardian moves in by a council officer. We do the work, we take the council round, they sign it off."

The council has also developed a comprehensive policy on the use of guardians. "The council is committed to ensuring that temporary guardians are treated fairly and appropriately and the contract provides an opportunity for people who have limited housing options," says the detailed policy document, provided to IBTimes UK. "For example, the contract allows the council to set the licence fees paid by guardians, if necessary."

Bristol council uses guardians to secure 20 vacant properties. While some of these guardians are sought through the private firms Ad Hoc and Camelot, the homeless charity St Mungo's also provides people to live in the buildings. Bristol council does not charge the guardian companies or St Mungo's a fee to use its vacant buildings.

"The council does not have a set policy on the use of property guardians to secure void properties [...] The current guidance is, however, to look at the use of void properties firstly for homeless use, before looking at other meanwhile uses," said Bristol council.

The most commonly used guardian company among councils was Ad Hoc, followed by Camelot and VPS. In one unusual case, Southend Borough Council uses guardians to secure vacant buildings through its commercial subsidiary South Essex Property Services.

"Please be advised that South Essex Property Services are a private limited company and therefore do not fall under the scope of the FOIA," said Helen Walker, a corporate services officer at Southend council, when asked for information.

A much clearer legal framework

Berry is pushing for greater regulation of the sector and a common set of standards. She said she knew of one case where a warehouse owner deliberately split the vacant building into units for property guardians. "Now that's just becoming a slum landlord, in my opinion. That's not what we want," she said.

"But if we've got genuinely temporarily empty residential properties, they should not be left empty and therefore short-term tenancies, flexible tenancies, might be a suitable thing for a small proportion of the market.

"What I don't want to see is the whole sector expand and expand so that if we get improvements for private renters, which I am also working on, they suddenly don't apply to half the market. That would be terrible.

"So it's about striking that balance and using it for genuinely temporarily empty homes on a temporary basis but with a much clearer legal framework, a much clearer code of conduct, and people acting ethically — not exploiting people."

Camelot and Dex did not reply to emails asking for comment. Blue Door could not be reached.

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.