Right-to-Die Campaign: Hope for 'Martin' after Court Rejects Lawful Euthanasia in Nicklinson-Lamb Case?

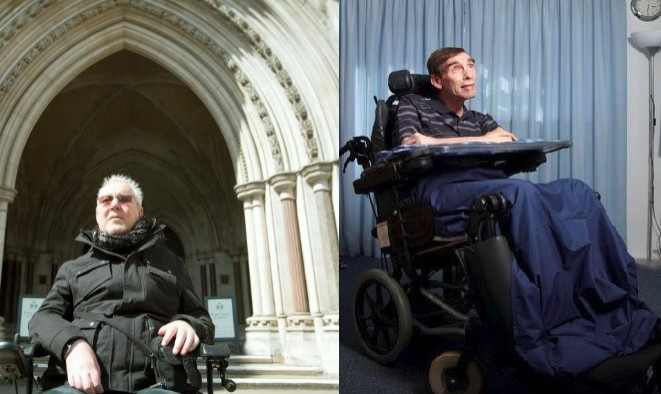

The Court of Appeal has given its judgment in the Tony Nicklinson, Paul Lamb and 'Martin' cases, involving three physically disabled men who challenged the laws that make euthanasia and assisted suicide illegal.

The ruling is unlikely to provide much comfort to Tony Nicklinson's family, who are continuing his fight for lawful euthanasia in the courts following his death in August 2012, or to Paul Lamb, who has taken Nicklinson's place in the judicial review proceedings.

Part of Martin's appeal, which was argued on different grounds to that of Nicklinson and Lamb, was successful.*

However, it is not guaranteed that his victory will allow him the death he wants.

Nicklinson and Lamb

Nicklinson and Lamb argued that the common law (the body of law made by the Courts) should recognise a defence of necessity in cases of euthanasia- a legal recognition that it is not murder when a person ends the life of another person at his request, because death is the only way to relieve unbearable suffering.

Nicklinson and Lamb, with Martin, also argued that the article 8 of the European Convention on Human Rights, which protects the right to private life, required a relaxation of the blanket bans on euthanasia and assisted suicide (assisted dying).

They claimed that the complete prohibition of assisted dying, which is designed to protect vulnerable people from abuse, disproportionately interferes with their right to decide when and how to die, since they are not vulnerable.

Essentially, the Criminal Law prohibits more than is necessary.

Unsurprisingly, the Court of Appeal was as unwilling as the Divisional Court in 2012 to develop the common law in order to allow necessity as a defence to murder.

It also held that the blanket prohibitions on assisted dying were compatible with the right to private life. As was the case in the Divisional Court, a feature of the Court of Appeal's reasoning was that legal change on assisted dying falls solely within the competence of Parliament.

Lord Judge, the Lord Chief Justice held:

The repeated mantra that, if the law is to be changed, it must be changed by Parliament, does not demonstrate judicial abnegation of our responsibilities, but rather highlights fundamental constitutional principles.

Political Environment

Last year, I argued that the political environment in the United Kingdom has made legislative action on assisted dying extremely unlikely.

MPs are in the business of staying elected; supporting legalisation of assisted dying runs the risk of rapid political demise.

If Lord Falconer's Assisted Dying Bill, which would only permit assisted suicide for the terminally ill, makes it through the House of Lords in the next year, and that is a big if, it will surely perish in the Commons as MPs scramble for re-election in 2015.

It is likely that Nicklinson's family and Lamb will appeal.

While they can expect great sympathy, it is unlikely that the Supreme Court justices will have a different view of the role of the judiciary on moral issues such as assisted dying.

Thus it appears little will change in the future, and Lamb and others in similar circumstances with similar his views will continue to suffer.

This is something we should all regret.

'Martin'

Martin's situation is different in that assisted suicide, most likely at Dignitas in Switzerland, is an option for him.

Following the House of Lords ruling in the case of Debbie Purdy in 2009, the Director of Public Prosecutions (DPP), Keir Starmer, issued the Policy for Prosecutors in respect of Cases of Encouraging or Assisting Suicide.

The Policy sets out a number of public interest factors tending in favour or against prosecution, which will be considered by prosecutors when considering whether to consent to prosecution for assisting suicide. In particular, prosecution is very unlikely when loved ones acting out of compassion assist the suicide of a person who has independently made up their mind to die.

Martin's wife respects his wish to die.

However, although she would likely escape prosecution, she is unable to assist his suicide for conscientious reasons. Martin, therefore, requires suicide assistance from a stranger, quite possibly a healthcare professional.

The ground on which Martin's appeal was successful relates to this predicament. Under article 8 ECHR, any legal measure that interferes with a person's right to private life must be sufficiently foreseeable and accessible.

Martin argued that the Policy violated article 8, since it does not allow a person without close personal ties to the person who dies to foresee whether they will be prosecuted for assisting suicide. This is because a number of the factors that point in favour of prosecution (acting as a healthcare professional, being paid for assistance, being motivated in part by financial gain, providing assistance to several people), may coexist with the factors that count against it (being wholly motivated by compassion, attempting to dissuade the person, assisting only with reluctance).

A majority of the Court of Appeal agreed. The Master of the Rolls, Lord Dyson, and Lord Elias held that 'it [was] not sufficient for the Policy merely to list the factors that the DPP will take into account in deciding whether to consent to prosecution', since without some idea as to how the factors were weighted assistors were not able to foresee the consequences of their conduct to the degree required by article 8 ECHR.

In particular, their Lordships found the policy lacking in respect of the clarity it provided to healthcare professionals: 'the Policy does not provide medical doctor and other professionals with the kind of steer ... that it provides to relatives and close friends acting out of compassion'.

What Does This Victory Mean for Martin?

In the short term, very little.

Shortly after publication of the Court of Appeal decision, the DPP announced that he would apply for leave to appeal to the Supreme Court prior to amending the Policy.

Assuming that permission to appeal will be granted, it is likely to take some time before the case comes before the Court. In the long term, even if Martin ultimately prevails, which is uncertain in light Lord Chief Justice's powerful dissenting judgment, there is no guarantee that the Policy will be amended in his favour.

If a revised Policy were clearly to set out that, for example, a healthcare professional who assisted him to travel to Dignitas in return for reasonable remuneration would likely be prosecuted, it would meet the requirement of foreseeability. This might indeed be the route the DPP chooses to take; like the judiciary, he is mindful of the constitutional boundaries of his office.

No doubt he is also acutely aware of the trouble that would follow were a revised Policy to resemble a law under which healthcare professionals were able to provide suicide assistance relatively free from the risk of prosecution.

Such a policy, however, would be very welcome among individuals in Martin's situation.

* Martin is a pseudonym.

Isra is a PhD candidate and visiting tutor at the Centre of Medical Law and Ethics, King's College London. His PhD project, 'Better off dead? Best interests assisted dying', develops and defends a new model for legalisation of euthanasia and assisted suicide in England and Wales. During the summer of 2013, Isra will be a fellow at the Foundation Brocher, an organisation that hosts researchers from all over the world who dedicate their work to ethical, legal and social aspects of medical development and public health policies.

Professor Penney Lewis, also at the Centre of Medical Law and Ethics, has written a short comment on Martin's case on the Centre's blog.

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.