Romania still haunted by the Holocaust even as Jewish survivors win decades-long legal fight

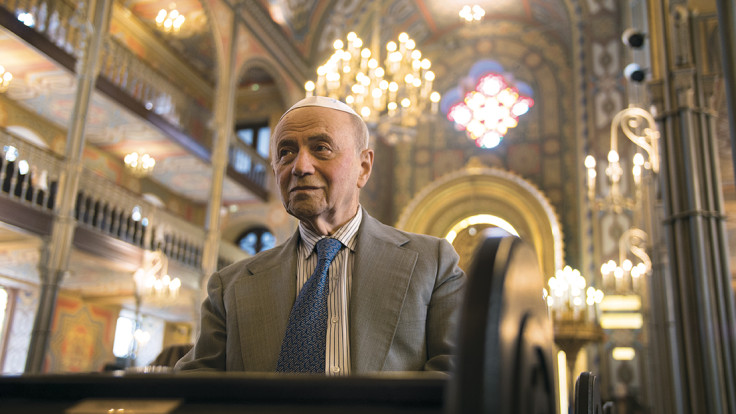

Leaning on a dark wooden pew in a central Bucharest synagogue, 88-year-old Liviu Beris recounts his desperate thirst as a young Jewish boy in a concentration camp some 75 years ago. Romania has this week passed legislation to expedite property restitution claims for Holocaust survivors — with overwhelming parliamentary support — but that appears to be of little concern to him now: "It's not just too little, it's too late," he says. "Holocaust survivors are old and dying."

During the Second World War, many Jews – Beris' family included – had property seized by the state, and were sent to forced labour camps or ghettos. Communist rule that followed the war nationalised properties from 1947 until its collapse in 1989. Since then, many Romanian Jews have been waiting for their property and homes to be returned to them.

"I couldn't seek restitution because what property was taken from us by the state is now part of Ukraine, from when it was taken over by the Soviets," says Beris, who was evacuated with his family from their home in Northern Bucovina when he was 13 years old.

A change in the law

The legalisation amendment is largely a result of initiatives led by the World Jewish Restitution Organization (WJRO) and the Federation of Jewish Communities in Romania.

The former said in a statement that the law could benefit at least some of the 40,000 claimants who have been waiting over a decade for an outcome. But despite the law change being widely applauded, critics believe that the Holocaust – though officially acknowledged at a state level – is often downplayed.

"There is the issue of education, the curriculum for national history does not include a separate, one-hour class about the Holocaust in Romania, and what information there is is presented in a way that distorts or minimises this historical episode," said Alexandru Climescu, a researcher at the Elie Wiesel Insitute.

Under the fascist military dictatorship of Ion Antonescu during the Second World War, 280,000-380,000 Jews were killed by the Romanian state within territories under its control. After the war, Romania suffered during four decades of hardline Communist rule under a regime that not only downplayed the state's role in the Holocaust, but also aimed to blot it out of existence.

Forty years of silence on the topic left a hole in wider public understanding that has lasted until the present day. Only as recently as 2015 did Romania ban the explicit public denial of the Holocaust, an offence that carries a three-year prison sentence. And yet, Climescu says: "Marshall Ion Antonescu is viewed by almost half of the population as a great patriot, a great Romanian [and] a devoted leader."

On a tree-lined Bucharest boulevard sitting in his modest office, Dr Alexandru Florian, Director General at the National Institute for Studying the Holocaust in Romania, explains the issue of anti-Semitism that remains in Romania.

Before the war, Romania had a Jewish population of around 800,000, a figure which today stands at around 9,000

"There is a latent anti-Semitism in the wider population. The general climate for Romanian Jews is normal, we don't have any extremist party in parliament; policy and public institutions have a democratic nature, they don't restrict the rights of minorities, but hostile manifestations towards Jews are coming from individuals — which are most aggressive in the online anonymous environment," he said.

An opinion poll carried out in 2010 by The Foundation for Open Society, which questioned 5,000 Romanian school pupils between the ages of 12-18, asking which ethnic minorities they wouldn't want to live next door to, revealed that 34% didn't want to live next door to a Jew, while 75% and 68% respectively were against homosexuals and Roma travellers.

Education is the word that crops up most when speaking to the Jewish community in Romania about the Holocaust. That more is effort is needed and that this part of their identity and history should not come as a mere afterthought.

I don't have an opinion of whether it's too late, it's just good that it's being done.

The new legislation would only be applicable to living Holocaust survivors, which means it would need to be actioned at speed to make any impact as most of those people, like Beris, are now in their 80s and 90s. Romania has joined a small wave of similar recent law changes implemented throughout former Communist Europe.

Some, however, have questioned the motivation for this latest legislation change. Valentin Mandache, an expert in Romania's historic properties, says: "It is just another political move at the pressure of European Union, the United States and international organisations of Holocaust survivors threatening Romania with sanctions. The great pity is that such an initiative never came from a grass-roots movement — which speaks volumes about the real agenda of the Romanian politicians and their voters."

Before the Second World War, Romania had a Jewish population of around 800,000, a figure that today stands at around 9,000. Seventy percent of the Jewish population are now over the age of 70, and there are very few births annually in this community.

Romania has been slow in coming to terms with its treatment of Jews during the war and equally slow to implement measures to help survivors and to confront its part in the Holocaust.

"I don't have an opinion of whether it's too late, it's just good that it's being done," Florian says.

Stephen McGrath is a freelance journalist based in Bucharest

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.