Scientists create 'mini liver tumours' in cancer research revolution

Development could pave the way for personalised cancer treatments.

For the first time, scientists have created miniature liver tumours in the lab which mimic the real thing, opening up new avenues for research into potential treatments for liver cancer - the second deadliest form of the disease.

Previously, researchers had used cell cultures for research purposes but these are difficult to maintain and not as effective in mimicking the attributes of human tumours in the body.

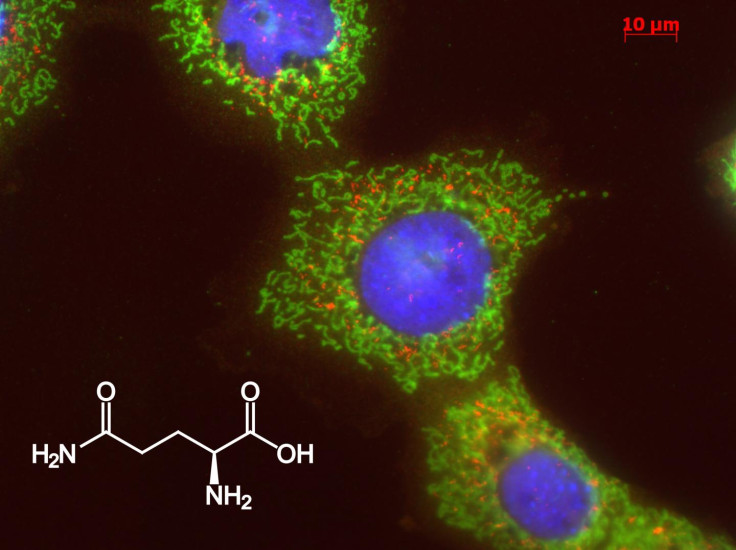

For the study, published in the journal Nature Medicine, a team from the Wellcome/Cancer Research UK Gurdon Institute at the University of Cambridge created mini tumours - known as tumouroids - measuring up to 0.5mm designed to emulate the three most common types of liver cancer. They were created by taking tumour cells from cancer patients and growing them in a special solution.

They then used the tumouroids to test 29 different drugs, revealing the potential of the mini tumours in identifying effective new treatments.

For example, the researchers found that one compound was especially good at blocking a crucial biological process in the development of liver cancer. They then tested this compound in mice who had the tumouroids transplanted into them, finding that there was a marked reduction in tumour growth. This proved that the compound could be used to treat some types of liver cancer.

"We had previously created organoids from healthy liver tissue, but the creation of liver tumouroids is a big step forward for cancer research," said Meritxell Huch from the Gurdon Institute. "They will allow us to understand much more about the biology of liver cancer and, with further work, could be used to test drugs for individual patients to create personalised treatment plans."

Andrew Chisholm, Head of Cellular and Developmental Sciences at Wellcome said: "This work shows the power of organoid cultures to model human cancers. It is impressive to see just how well the organoids are able to mimic the biology of different liver tumour types, giving researchers a new way of investigating this disease. These models are vital for the next generation of cancer research, and should allow scientists to minimise the numbers of animals used in research."

The team say that the tumouroids are biologically indistinguishable from their parent tumours. Because of this, they could allow researchers to develop personalised treatments.

The new development will also reduce the number of animals needed at certain stages of research as scientists will be able to carry out experiments using the tumouroids instead (although animals will still be needed to validate certain findings).