Scientists develop life-saver robot to help damaged heart ventricles pump blood

The new device can selectively assist either left or right ventricle of the heart to restore blood flow.

Scientists have developed an implantable robotic device that squeezes the heart gently, allowing it to pump blood and beat properly. The device may take up to three years to hit the market, pending further tests and human trials, the makers reportedly said.

The heart is divided into two chambers — the left ventricle that pumps blood to the body and the right ventricle that pumps blood only to the lungs. In most patients suffering from heart ailments, only one of their ventricles malfunction while the other is still healthy. The robotic device is capable of choosing and assisting the damaged ventricle.

Nikolay Vasilyev, one of the researchers who unveiled the device, says at least 26 million people suffer from heart failure across the world. Many are born with congenital conditions where the organ fails to pump sufficient blood required by the body.

The only possible cure so far has been heart transplant, but this robotic device could prove to be a life-saver, he points out.

"We set out to develop new technology that would help one diseased ventricle, when the patient is in isolated left or right heart failure, pull blood into the chamber and then effectively pump it into the circulatory system," Vasilyev explains.

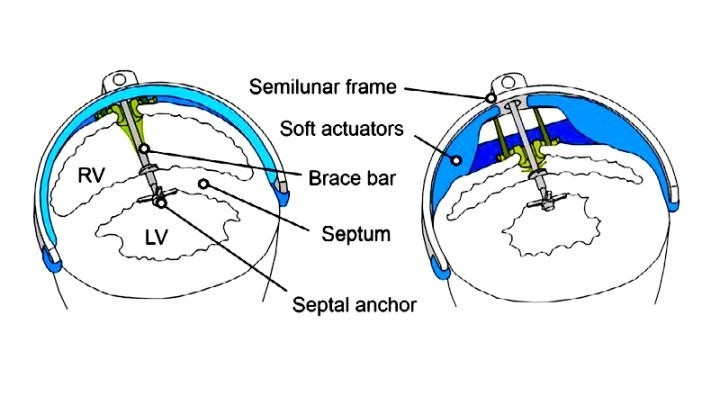

According to a report in The Verge, the new device carries three main parts — a frame that wraps the heart from one side, an anchor that goes inside the heart through a small cut, and a soft muscle-like actuator that moves to squeeze the heart and maintain the flow of blood.

The anchor braces the wall separating the left and right ventricle and keeps it in its original position, protecting the healthy side of the heart from the load of the soft actuators. Meanwhile, the actuators squeeze the heart from outside and trigger pumping mechanism only in the diseased ventricle. The process initiates with the pumping of compressed air into the device.

So far, the new device has only been tested on pigs and for just one hour, suggesting that it is in the early stages of developments, with more tests required before it can be ready for clinical human trials.

"We are planning to conduct long-term validation of this technology in chronic animal studies and then move to first-in-human clinical studies," Vasilyev told Seeker. "Bringing medical devices like this one to market takes a long time due to [a] lengthy regulatory pathway and may take up to two to three years."

The new technology could also offer a better alternative to existing heart pumps, which expose the blood to their unnatural surface.