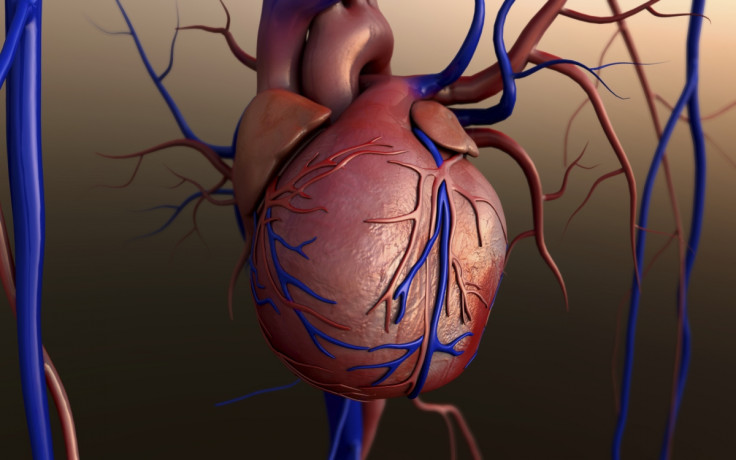

Scientists reverse severe heart failure in animals

The researchers discovered an unknown healing ability in the heart muscle.

Scientists have reversed advanced heart failure in mice after discovering a previously unrecognised healing capacity of the heart muscle. They did this by silencing the activity of a biological pathway – called Hippo – which can prevent the regeneration of heart tissue.

Developments such as this could one day lead to new treatment options for advanced heart failure, which kills thousands of people in the UK alone every year.

The organ fails when the muscle does not have the strength to pump blood around the body, with symptoms including shortness of breath, swelling and fatigue. Its main causes are heart attacks, high blood pressure and diseases that affect the muscle.

"Heart failure remains the leading cause of mortality from heart disease. The best current treatment for this condition is implantation of a ventricular assist device or a transplant, but the number of hearts available for transplant is limited," said James Martin, an author of the study from Baylor College of Medicine in Texas. The research was published in the journal Nature.

Most people who have suffered severe heart attacks will develop heart failure one day. This is because during a heart attack, blood stops flowing into the organ, starving it of oxygen and causing parts of the muscle to die.

These damaged areas do not regenerate and are instead replaced with scars made of cells called fibroblasts, which make it difficult for it to pump properly.

"One of the interests of my lab is to develop ways to heal heart muscle by studying pathways involved in heart development and regeneration," Martin said. "In this study, we investigated the Hippo pathway, which is known from my lab's previous studies to prevent adult heart muscle cell proliferation and regeneration."

"When patients are in heart failure there is an increase in the activity of the Hippo pathway," said John Leach, first author of the study and a graduate student in Martin's lab. "This led us to think that if we could turn Hippo off, then we might be able to induce improvement in heart function."

"We designed a mouse model to mimic the human condition of advanced heart failure," Leach said. "Once we reproduced a severe stage of injury in the mouse heart, we inhibited the Hippo pathway. After six weeks we observed that the injured hearts had recovered their pumping function to the level of the control, healthy hearts."

The researchers think that turning off Hippo encourages the muscle cells to proliferate and survive while also affecting the fibroblast cells, although more studies are needed to understand precisely what is going on and how the new knowledge can be implemented in future treatments for humans.

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.