SEZ 2.0: Inside India's failed 'free trade zones' where the economic miracle is a mirage

Gates and walls surround the industrial complex 15 minutes' drive from the nondescript town of Gandhidam in Gujarat, but walking through them unescorted and unquestioned by security is easy. The roads are wide and desolate: no one walks and there are few cars. Factories line the streets on either side of the 1.2sq-mile site.

Inside the Sharda Metal Industries factory on the main thoroughfare, workers hammer out stainless-steel kitchen products for the European and American market. The men work in close quarters in the intense heat and darkness, sweating as they beat the steel into shape before polishing it. This tract of land not far from the Pakistani border was carved out during the Cold War in 1965 by non-aligned India as Asia's first Special Economic Zone (SEZ), a new 'extra-territorial space' that was not bound by national laws and provided a favourable tax and customs regime, as well as infrastructure, that would bring companies and investors into countries where national policies might otherwise put them off.

Because there are so many industries and the labour force is limited, workers can find many opportunities inside the zone. Because of the shortage of labour they try to grab the labour from one company to another company. So because of the demand it is becoming costlier

The Kandla Special Economic Zone (KASEZ) has operated for 50 years. Yet it is signalled only by a decaying sign and long stream of heavy freight going in and out.

The SEZ model would later storm the world, diversifying into Export Processing Zones, Economic Free Zones, Enterprise Zones and other variants. Many top officials in the Chinese government thank the SEZ model for that country's precipitous rise to superpower status. The Chinese established their first SEZ in 1980 at Shenzhen on the border with Hong Kong and have never looked back.

Changing times

The number of countries that have some type of contemporary industrial zone has boomed since the 1990s, as post-Soviet and African states increasingly bought into this quick fix concept to attract foreign investors. Recent zone announcements from Djibouti, Mozambique and South Sudan would add to the more than 4,000 that are already in existence. Even the Cayman Islands followed suit in 2011 and set up a niche 'tech zone' that pushes the tax haven's neo-liberal policies one step further.

The residents of KASEZ are more circumspect. Viren Karani, a partner at Sharda, said that when the company moved to the zone in 1976 the incentives were lucrative, but in the years since India's business landscape had opened to the extent that the benefits of the SEZ was redundant. Now Sharda was trapped in the zone while competitors were able to get at least as good tax breaks and incentives outside.

"When the zone started [...] there were incentives: importing was free, no duty was allowed, so for that reason the factory was set up here. [But] after spending so much setting up here, you can't go out if there are issues now. The SEZ model is a successful model, but the benefits that are being given to people outside are not being given to people here," he said, adding that in some cases benefits were better outside the zone.

"There are some export benefits for people who are exporting from outside. We in the SEZ don't get those – the same benefits are not being given to the older companies over here. So the competition is tough between the local supplier and the SEZ supplier."

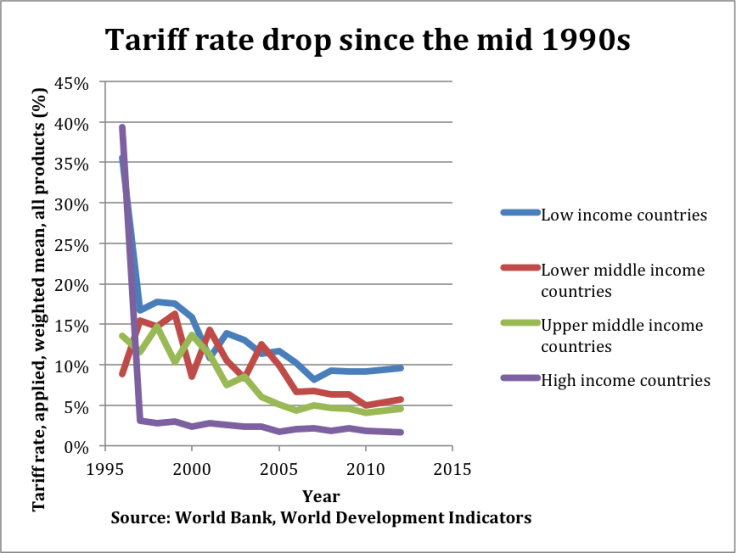

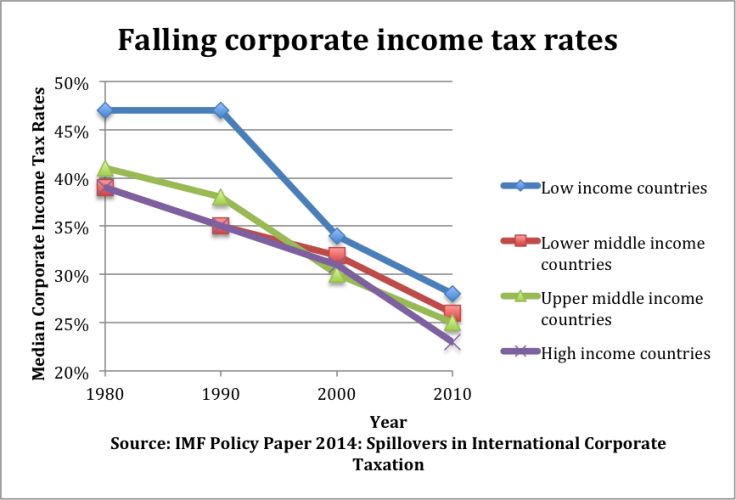

Karani points out something that many believe is making SEZs obsolete in the 21st century, even as their numbers grow. The process of trade liberalisation – and the global 'race to the bottom' to attract investment – has seen corporate tax rates and tariffs cut drastically, meaning that having carved out zones where customs duties and taxes are exceptionally low are increasingly unnecessary.

"They are fairly anachronistic, especially in Western countries," said Patrick Neveling, a social scientist at Utrecht University who is a specialist on SEZs. "But from a rational perspective these zones have always been anachronistic, because they continue a colonial era plantation-style system."

Nevertheless the Indian government is not slowing down in promotion of the SEZ model. In 2005, the Indian parliament passed the Special Economic Zone Act, under which the state now governs all SEZs in the country. Between the 1960s and early 1990s India built seven economic zones, but by the end of the 2000s there were more than 500 in various stages of planning, construction and operation.

Chinese liberalisation

Critics highlight that the political excitement surrounding these quick-fix policy zones is hard to square with the facts. The cost of infrastructure investments and foregone tax revenue are certain, whilst strong job or trade boosts from these zones have been isolated to a few unparalleled success stories, mainly in China.

While they might have played a catalytic role in the Chinese liberalisation process, the global lowering of tariff and corporate tax rates might undermine the value that an SEZ can offer. Nonetheless, political parties on left and right have pushed SEZs as strategies to attract foreign capital, create jobs and boost investment. At the height of its operations, Kandla was exporting many of its products to the Soviet Union.

"In 1965, India was very deficient in foreign exchange," said Krishan Kumar, joint development commissioner of KASEZ, in his office just outside the zone's walls. "So that was always one of the main objectives of that time – to earn foreign exchange for the country. And in some way create exports from this country, because if you compare that time we had an import trade but a negligible presence in world market in terms of exports."

The initial success sparked the interest of their Chinese neighbours. "I have heard even Chinese came here sometimes in 1970s and early 1980s. And now obviously the Chinese have taken the lead and gone far beyond us."

China has since introduced its own take on SEZ, with larger zones than the classic SEZs that often combine residential, commercial and industrial activity. Chinese private and state-owned corporations, backed of the Chinese government's 'zones abroad initiative', have planned or initiated up to 50 zones on foreign soil. While most zones in the first wave of SEZs, such as the KASEZ, are still administrated by the local authorities, private operators are quickly becoming the new mainstream. The World Bank FIAS program conducted a stock check in 2008 and found that 62% of the 2,301 zones in developing and transition countries were privately owned.

The first modern-day industrial zone is said to have been in Shannon in the west of Ireland in 1959, which set one up as an accompanied to the airport which was a transatlantic stopping point. But EU state aid rules have introduced new regulations on economic zones in Europe, making it illegal for governments to offer specific incentives to companies in defined geographic areas within their territories.

Further into KASEZ, as the rain beats down, the Universal Confectionary & Food Products factory comes into view. Kiran Mistry, the factory manager, is more optimistic about what the SEZ gives the companies it houses. "All the exporters are benefiting by being in this zone in terms of taxes," he says. "[But] outside labour is actually cheaper and you can get better people, here it is a bit costly. Because there are so many industries and the labour force is limited, workers can find many opportunities inside the zone. Because of the shortage of labour they try to grab the labour from one company to another company. So because of the demand it is becoming costlier."

As the wave of SEZs that emerged since 1959 are becoming increasingly anachronistic, a new forefront of neo-liberal experiments is in the making. 'Model Cities' to some, an extreme libertarian experiment to others, Honduras is planning the establishment of completely chartered cities entitled Zones for Employment and Economic Development (ZEDE). The idea stems from the American economist Paul Romer and aims to replicate Hong Kong's success where direct democratic oversight of whole cities is to be replaced by business-friendly regimes. While ZEDEs are now established under Honduran law and preliminary deals have been signed, the realisation of this SEZ 2.0 remains to be seen.

Travel funding for this article was provided by the Pulitzer Center on Crisis Reporting. Matt Kennard's new book, The Racket, is out in paperback next month.

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.