Shark attacks: How to protect yourself

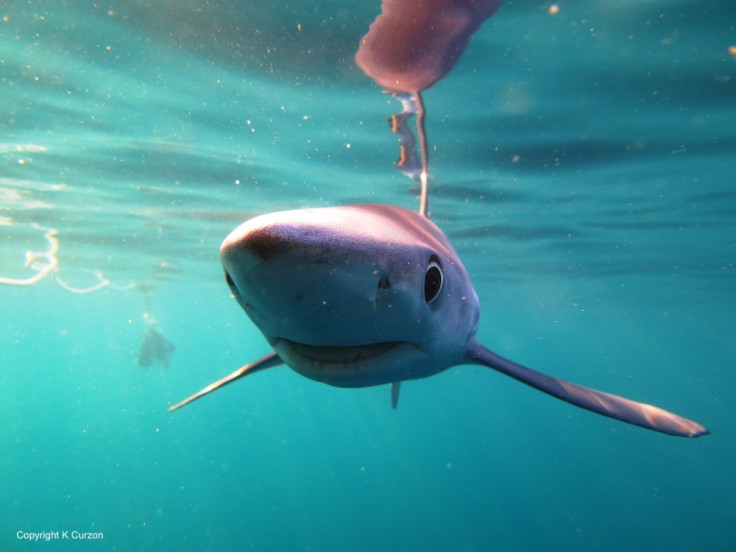

Kathryn Curzon, great white shark safari guide, tells IBTimes UK how to deal with a fear of shark attacks.

Thank Jaws for a generation of people genuinely terrified of entering a body of water. Ask anyone, even if they've never seen the film before, and they'll tell you it's a story of a bloodthirsty shark who seeks out human prey - that's how impactful it's been in popular culture and, more importantly, establishing how we see sharks today.

Our reliance on film portrayals of them has meant that as a whole, we do not actually know very much about sharks. As a result, our connotations of violence could be completely unfair.

Kathryn Curzon is a diver and writer for Liveaboard.com, a website to book cruises, and a trained scuba diving instructor and great white shark safari guide. She spoke to IBTimes UK and set the record straight about these toothy, ominous creatures.

The important thing she notes firstly is that shark attacks are incredibly rare.

"The International Shark Attack File (ISAF) at the Florida Museum of Natural History [records the number of attacks every year]. There were 84 confirmed cases of unprovoked shark attacks worldwide in 2016. In 2015, the ISAF reported 98 shark attacks," she says. The Australian Shark Attack File reported that two people died because of shark incidents in Australia in 2015 and that there were five fatal shark incidents in 2014.

"The overall small increase in shark incidents in recent years is likely due to the growing human population and increase in water users. It is becoming ever-more popular to spend time in the ocean and this alone increases the possibility of an incident occurring.

"In the period 1995-2010, an average of one person died per year from a shark incident in Australia. These are small figures for a country with a perceived high risk of shark attacks occurring and a population size of over 23 million people (as at June 2015)."

Can you reduce your risk of an attack?

Absolutely, says Curzon, who points out that remembering the risk of it happening is really slim and that alone can stop people acting out of fear and instead, enjoy themselves.

Swimmers should avoid certain times and certain kinds of waters. Sharks can be found in all five of the Earth's oceans: the Atlantic, Pacific, Indian, Arctic and Southern. Different species prefer different climates, however.

"Two of the easiest things to do are to avoid being in the water at dawn and dusk, and avoid being in low visibility water. Dawn and dusk are times of low light conditions, and are times when sharks may be hunting. A diver or other water user is more likely to be misidentified by a shark and potentially bitten if the shark cannot see it clearly; be that because of low light or because the water is murky."

Another tip is to dive with a group of people - especially in an area known for sharks. This means there are multiple eyes and ears. She also recommends planning a group response if you happen upon one. She uses "descending to the reef floor until a shark has passed (if safe to do so), or exiting the water slowly whilst maintaining eye contact with the shark" as examples of this.

"One of the most interesting aspects of sharks is their unique behaviours and ways of communicating. Get to know shark behaviour before getting in the water with them. They are intelligent animals and use body language to signal when they feel threatened by a diver's presence; such as jaw gaping, arching their back, and lowering the fins at the side of their body."

Sharks are not immediately aggressive however and misconceptions suggest that they are man-eating and deliberately threatening to humans. Instead she notes how "in almost all [shark attack] cases, the shark bites once and let's go, realising the person is not a food source. Sharks have very acute senses, and much like a puppy or baby, they will mouth objects to establish what they are."

Ultimately, the best thing to do is swim away calmly if you encounter one and feel uncomfortable. Panicking and thrashing will only make the shark more curious and likely to approach, she says.

What should you do during a shark attack?

"The International Shark Attack file suggests divers encountering a shark acting aggressively should cut off the angles of attack by backing up against an object, such as a rock. If in open water, divers should position themselves back to back and ascend safely to their boat. Shore divers should descend to the bottom to find cover, if safe to do so" she says.

Sharks' noses are sensitive so a prod with any equipment you have - a camera pole for example - would give you enough time to swim away.

Although she says it's extremely unlikely, "if bitten and held in a shark's mouth, the person should be as defensive as possible and aim to strike the eyes and gills if possible. Once released by the shark, the person should exit the water swiftly and of course seek medical attention."

As for carrying knives or other objects as defence, she says that lots of divers carry the former but not for this reason. If they want something to defend themselves with they will take a pole when diving in an area known for sharks. Simply extending the pole with your arm can be enough to deter a shark as it creates a larger distance between the two.

"Acting aggressively towards a shark with a knife (or a pole) is not a good idea, as it could provoke a shark to bite when it otherwise wouldn't have done so."

Ultimately, for anyone still harbouring any fear she reminds us that "sharks have far more to fear from us than vice versa. With our appetite for seafood and indiscriminate fishing techniques, we are pushing various shark species towards extinction."

Kathryn Curzon is co-founder of the marine conservation cause Friends for Sharks.