Snooper's Charter: Why aren't VPNs and Tor mentioned in the Investigatory Powers Bill?

On 4 November, UK Home Secretary Theresa May outlined new laws that would give law enforcement and government intelligence agencies the power to snoop on the private data of anyone in the UK, but surprisingly, nowhere in the proposal does it mention the use of Virtual Private Networks (VPN).

The Investigatory Powers Bill, also known as the "Snooper's Charter", was laid out in a 299-page document that outlined the changes the UK government wants to make in regards to the interception and hacking of devices and computers in order to access information when investigating a case.

The main points of the bill, if it is passed, include the fact that internet companies must hold people's web and social media use data for up to a year (but not specific browsing history or content of communications); tech firms will be legally obliged to help government agencies access a user's data; law enforcement hacking your devices can be OK; and what is said to a journalist, doctor, lawyer or even MP might no longer be entirely private.

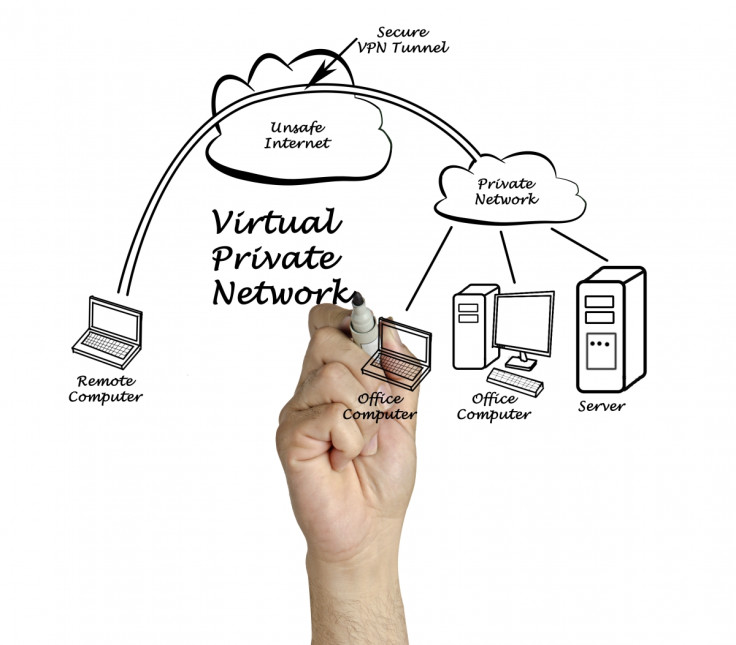

However, The Stack noticed an interesting point – nowhere in the draft legislation are VPNs mentioned. VPNs are subscription services that work by fielding users' internet traffic through a protective communication protocol across the web, so you cannot tell where it originated from.

VPNs are tunnels that encrypt your web traffic

This is useful not just for protecting a user's activities online but also to help trick geographically restricted video content services such as Netflix, BBC iPlayer and the NBC TV app service, or enabling citizens to access services like Facebook, Google and Twitter in countries where the internet is censored, such as Turkey or China.

Most VPNs have to paid for because the user is essentially paying to route their internet traffic through a private server in order to connect to websites such as Facebook or Netflix (there are free ones, but some of them are not great).

This also means if the user does anything illegal, the police will go after the VPN provider and either ask it to suspend the user's account or to divulge the user's account details and IP address.

Another thing missing from the draft legislation is any mention of the Tor anonymity network. Tor (from The Onion Router project) is the name for software that anonymises and redirects internet traffic through a worldwide network of relays comprised of volunteers who set up their computers as Tor nodes.

Because the data travelling between any two nodes on the network only contains the details of those nodes, the source and final destination are effectively anonymised and protected from interception, and every Tor path is protected by at least three layers of encryption (ie three nodes).

Both Russia and China hate Tor and VPN

Put Tor together with VPN and it is possible to fully encrypt your internet traffic so no one can tell where you are, while all the VPN provider can do is shrug its shoulders when asked by intelligence agencies.

So it is surprising that these technologies have not been mentioned in the bill, as far as other countries such as Russia and China are concerned. In January, China updated its firewall to block several popular VPN services from being used, while Russian politicians proposed banning the technology in February. And in July 2014, the Russian federal government offered 3.9 million roubles ($111,000, £65,370) in a competition to find a solution for cracking Tor.

So why aren't VPNs and Tor mentioned in the Investigatory Powers Bill? Is it because the UK government is classing VPN and Tor node hosts as "communication providers", and thus this means they are legally obliged to decrypt a suspect's internet traffic? Or is it because it is not worried about the use of the technologies yet?

Whatever it is, if the laws go ahead, more users could start using VPNs and it would not be surprising if services begin to build VPNs into their functionality.

Sebastian Lahtinen, co-founder of thinkbroadband.com, told IBTimes UK: "Whilst this type of security activity may only currently be used by a small number of privacy-conscious individuals for personal security, with most using the default settings on phones and applications they use, these tools are likely to become easier to use and will in due course become more prevalent.

"It would be a foolish criminal or terrorist who did not consider use of [VPN] and relied solely on systems provided by the major companies likely to be required to weaken their protections under this law."

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.