Something terrible is happening in Manila - how can the world turn a blind eye?

Drugs are a problem in the Philippines – the real issue, though, is poverty.

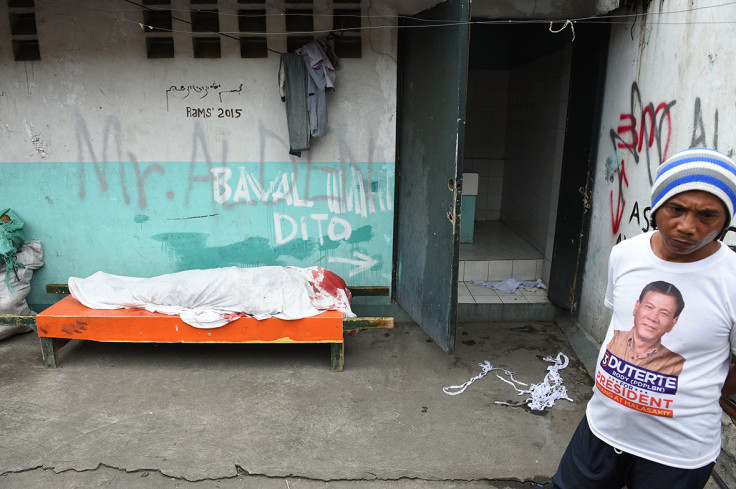

Each night a group of local and international journalists gather at Manila's main police station and wait for a call. Sometimes it is one body, sometimes two – occasionally three. What is almost certain is that the call will come, and that van-loads of writers and photographers will hurtle out into the city to document yet another death in President Rodrigo Duterte's war on drugs. It is soul-draining in its monotony. The bullet-ridden bodies of loved ones merely become the subject of small talk.

During one strikingly depressing 'night shift', I witnessed two bodies being shovelled into the back of an ambulance without so much as a witness statement having been taken. Local boys laughed and played as the police read out a statement to the media. Later, a local man would tell me, the actual body count was three.

You would expect most Filipinos to oppose this bloodshed. Quite the opposite: around three-quarters of those with whom I spoke still spoke highly of Duterte. Kids wore 'Du30' t-shirts and held out their fists, smiling, in the president's iconic 'punching' stance. One local leader handed me a bunch of Duterte-branded, red-and-blue wristbands. Whatever your opinion one thing is clear: Duterte has got his branding on-point.

Mothers who expressed a mortal fear for their own children chided the police, and not the president, for his brutal campaign. "Give him more time," one woman, in a particularly depressed part of town, told me. Her own son had recently been picked up in a tokhang –knock and plead – raid by masked local police. He took shabu, a cut-price crystal meth, occasionally. One more encounter combined with a 'resist' – real or faked – and he could legitimately be killed.

"The police are doing this, not Duterte," she said. When I suggested it was Duterte's order causing all of this – "if you know of any addicts, go ahead and kill them yourself," he said in July – she shrugged her shoulders: "I don't read the newspapers."

Duterte has manipulated his populace beautifully. If they don't know anyone using drugs they support him. If they know someone who has fallen foul of his system, they blame the cops. If they don't support him, it is because they feel duped by his pre-election rhetoric. Whatever the outcome, Duterte wins.

Drugs are a problem in the Philippines. The real issue, though, is poverty. Rarely have I witnessed a society where the line between rich and poor is so wide. Makati, a modern, Dubai-esque city on Manila's southeastern periphery, actually has a wall around it. People on its poorer side sleep leaning against it.

China, Japan, Singapore and South Korea—the Philippines' major trading partners—have remained obnoxiously quiet.

Many of Makati's tower blocks are owned by a cabal of families that have enriched themselves at the country's expense for decades. Duterte has been eager to attack bogeymen outside the Philippines – the EU, Barack Obama and even the Pope – but he hasn't attacked his own oligarchy. That is telling. Like all good populists, he is happy to expound on the fears of the poor without addressing any of their deep-seated problems.

That is why, despite having named a select few high-ranking officials and police, it is the poor who are almost always on the wrong end of Duterte's drug policy. It is their bodies that wind up riddled with bullets in the early hours. It is their relatives who, with no way to chase a killer, are left simply to cry and mop up the blood. Similar projects have failed in the region, notably in Thailand. Duterte must take note.

The Syrian War, a true calamity of our time, produces a similar number of bodies per day. That should alarm anyone. China, Japan, Singapore and South Korea—the Philippines' major trading partners—have remained obnoxiously quiet throughout this campaign. They must speak up. So, too, must the US and Europe, despite whatever vitriol Duterte deems fit for them. Something terrible is happening in the Philippines. The world is turning a blind eye.

Sean Williams is a freelance journalist based in Berlin. He recently returned from Manila, where he reported for IBTimesUK on the drug war being waged in the Philippines.

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.