Spamhaus Attack: Did Biggest Cyber-Attack in History Really Break the Internet?

Reports vary wildly of the seriousness of the Spamhaus attack, but did the biggest cyber attack in history really nearly break the internet?

A lot has been written in the space of 24 hours about a cyber-attack which has been labelled the "biggest in the history of the internet." We were initially flooded with reports of the attack breaking the internet, with users around the world suffering.

When people finally stopped reading the stories and got around to opening Netflix or visiting IBTimes.co.uk, the vast majority would have seen there was no affect at all. And so we had the article backlash, led by a well-written piece on Gizmodo which placed the blame squarely at the feet of Cloudflare, the company which boasted that it had help Spamhaus successfully mitigate the attack.

And so we have had a flurry of derivative pieces asking if this was all simply a PR stunt.

Here are the facts as we know them so far.

Spamhaus, an anti-spaming group which aids email providers by running a constantly updated blacklist of spam email servers, was over the last two weeks hit by several distributed denial of service (DDoS) attacks. These attacks have been attributed to Cyberbunker, a web hosting service based in Holland which was placed on Spamhaus' blacklist.

Cyberbunker doesn't deny carrying out the DDoS attack but does continue to deny that they host spam email servers.

Following the initial DDoS attacks Spamhaus contacted CloudFlare, a company which specialises in mitigating these type of attacks. In a blog post from last week, CloudFlare's CEO Matthew Pryce claims the attacks were 75 gigabits per second (Gbps) in size but were successfully deflected by CloudFlare's techniques.

Yesterday, Spamhaus' chief executive Steve Linford raised the bar by confirming the New York Times report that the attacks had subsequently reached 300Gbps, which is by an order of magnitude the largest publically known DDoS attack in history.

Feul to the fire

CloudFlare added fuel to the fire by posting an incendiary blog, again written by Pryce, with the title: The DDoS That Almost Broke the Internet" which didn't do anything to quell a growing sense of fear beginning to permeate the internet that things were about to go pear-shaped.

So was it the biggest attack in history and did it almost break the internet? Yes and no.

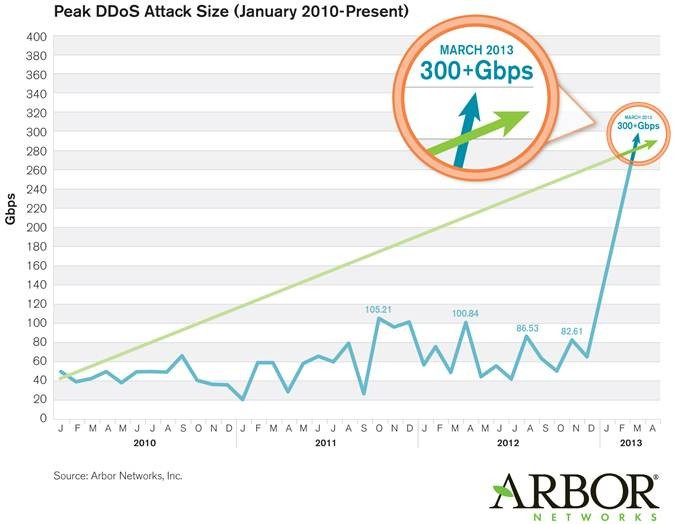

Yes it was the biggest DDoS attack which has ever been reported - and by some way. This graph by Arbor Networks clearly shows that a 300Gbps attack is three times larger than the previously biggest attack.

But no, the attack did not break the internet or come anywhere near breaking it.

While 300Gpbs of data being fired at a single data centre or ISP will almost centainly knock it offline, the backbone of the internet is made up of hubs which handle data measured in terabits per second rather than gigabits on a daily basis.

To knock one of these so-called Tier 1 operators offline would require something much more powerful than we saw with the attack on Spamhaus.

Reports from the New York Times and the BBC both claimed Netflix' service was affected as a result of this attack as well as global internet users seeing the affects when trying to access the web, but proof of this seems a little thin on the ground.

While this volume of data would have had a knock on effect on some web users, it would have likely been negligible.

Make a name

CloudFlare is clearly looking to make a name for itself while it is in the spotlight, but writing blog posts with fear-mongering titles will help no one, and only lead to more confusion.

While this type of attack is certainly not going to break the internet any time soon, the use of DNS Amplification as a technique for DDoS attacks serves to highlight a major problem facing those who are trying to mitigate such attacks.

DNS amplification is only made possible by DNS servers which are not locked down and according to the Open DNS Resolver Project "pose a significant threat to the global network infrastructure."

As of 24 March there are 25 million of these servers which "pose a significant threat" and which could be used by cyber-criminals or cyber-activists to carry out DDoS attacks of this size - posing a huge threat to ISPs and data centres, if not to the internet as a whole.

"What they [those operating these servers] are doing it that certain people haven't followed certain best practices," Darren Anstee from Arbor Networks says.

Anstee says Internet Service Providers should be filtering incoming traffic from their customers "because really your customers should only be sending traffic from the addresses you have given them. You shouldn't be accepting traffic with somebody else's spoofed IP address."

The internet isn't broken yet, and attacks like this are not likely to break it any time soon, but the media circus around breaking the internet means the bigger and more real problem of vulnerable servers is not being addressed.

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.