This is what it's like to drive Lewis Hamilton's F1 car - and stall it like a 17-year-old

We take on Circuit de Catalunya in the 2017 Mercedes-AMG simulator.

"This is not a computer game," we are warned before being ushered into a keycard-protected building which houses the Mercedes-AMG Formula One simulator.

Guests of technology partner Qualcomm, we gather in the simulator's control room, complete with eight large screens on the wall and 12 computers spread across three desks. We are then told how fewer than 10 of the team's 700 employees have driven this so-called 'driver-in-loop' machine, with even executive director Toto Wolff among those yet to have a go.

Instead, team drivers Lewis Hamilton and Valtteri Bottas make best use out of it, along with Mercedes test driver Anthony Davidson. Many hours are spent in this seat to discover how the real cars will react to each setup change the team makes.

Today we will be driving the 2017 car, as currently raced by Hamilton and Bottas. The car will be given 5% more grip than normal to accommodate for our butter fingers, plus a low fuel load to keep weight down. A six-axis rig which moves the cockpit in any direction to simulate G-force is deemed too violent for us amateurs, and is switched off. Otherwise, this is the real deal.

As we step into the bath tub-like cockpit, feet stretched out ahead, knees up high and toes almost at eye level, wrists and shoulders just centimetres from the edges of the carbon fibre safety cell, we are reminded that, during a three-year stint at Mercedes, Michael Schumacher managed just seven days in here, due to feeling nauseous.

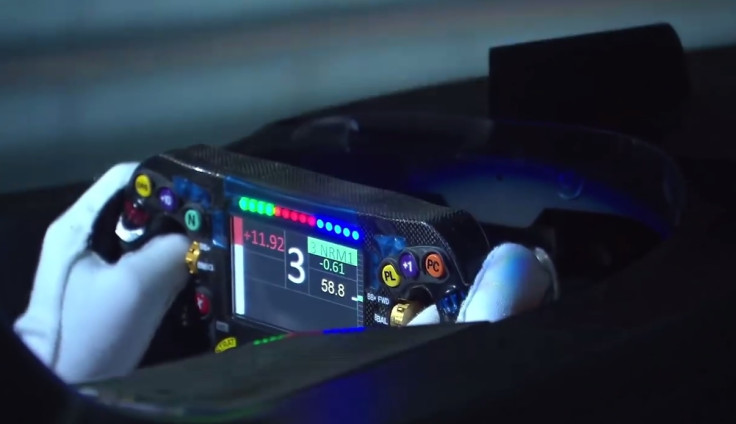

This year's steering wheel is slotted into place in front of us, its many LED lights blinking into life like a bizarre carbon fibre Christmas tree - a 'Christmas tree' which costs in the region of £50,000 and has over two dozen physical controls, some of which are dials with 16 options each.

Mercifully, this will all be simplified for us and our 10-minute session. A large smartphone-like display sits front and centre to show the car's vitals, and a row of lights illuminate from left to right to indicate when to change gear. Behind, sits a pair of gear shift paddles, plus two more to operate the clutch.

Also made simpler is the start procedure. Just like our first driving lesson a decade earlier, we will set off downhill in a move designed to smooth out our terrible clutch control and save the precious gearbox from eating itself. Dialing in the correct amount of revs (as indicated by messages on the screen) is surprisingly tricky, such is the speed at which they rise and fall as you move the accelerator. Too few and anti-stall kicks in, too many and something (if this were for real) goes bang in a terrifyingly expensive way.

One journalist smashes their way through three gearboxes before completing a lap - a devilishly easy mistake to make, and eye-opening when you consider the rules dictate each must last for six consecutive races in the 2017 season.

We select first gear, come off the brake, let out the clutch with an outstretched pinky finger and judder away, into the final sector of Barcelona's Circuit de Catalunya. The tyres, brakes and fluids have been made artificially warm so we can get straight on with it as we cross the line to start our first flying lap.

Slowing from eighth gear for the first right-hander, we brake too much and fail to pull the left paddle quickly enough to drop through the gears. Anti-stall kicks in, dumping us into neutral and resetting our brain to that of a 17-year-old being tasked with approaching a roundabout for the first time. Everything between our ears turns to mush as the calm, reassuring voice of an engineer feeds instructions through a headset. Neutral, clutch, first gear, try again.

What we have learned right away is how clumsy Formula One cars are at low speed. Even with warm tyres and a little extra grip programmed in, they navigate slow corners (or regular corners made slow by our ineptness) with the grace of a shopping trolley on a cobbled road.

Add in the immediate and intense nausea brought on by a fight between our eyes, brain and inner-ear, and we are wondering if a complete lap will even be possible. If the simulator was moving we might have felt better, but steering what feels like a real car towards a 270-degree screen literally wrapped around you causes more cerebral confusion than we have ever experienced, even from the best virtual reality.

Thankfully this quickly subsides, as does our low-speed clumsiness when we learn to trust the car, pushing through the physical and psychological barrier where grip becomes more aerodynamic than mechanical. Over the next couple of laps our own knowledge of the circuit comes flooding back and - sorry, Mercedes - we begin to treat it like a computer game. A game that just so happens to use a real F1 steering wheel, with real pedals attached to a simulator which runs on Windows 10, but also has the actual car's onboard computer installed somewhere along the way.

We brake a little deeper into corners and accelerate a little harder on the way out, building confidence but always acutely aware of the knife edge we are driving along. Brake slightly too hard, miss a gear change, turn a little too late, or feed the power in too eagerly and we will be in the gravel.

After 10 minutes we are told over the radio our time has come to an end. We pull up, put the car into neutral and clamber out. Our eyes and mouth are dry, our palms are damp and adrenaline flows through our veins. Our hands shake a little as we scribble down notes for this feature article.

Stumbling around a full 7.5 seconds per lap behind Hamilton's fastest time of this year's Barcelona Grand Prix had taken all the concentration we could muster.

Now let us add up everything else an F1 driver has to think about: tyre, brake and track temperatures, tyre wear, fuel level, weather, rivals ahead, to the side and behind, team radio messages, pit boards, mechanical failures, accidents, safety cars, yellow flags, blue flags, red flags...

Then there is the wheel itself; two buttons and four paddles on the back, six buttons and three scroll wheels under each thumb, plus three central dials with a combined 40 options and the need to drive one-handed for a moment to adjust them. Finally, 10 individual LEDs, a row of lights to indicate engine revs, and the display with gear, lap times, comparison to your last lap, battery status and more.

Quite how F1 drivers master all this, while piloting a 1,000-horsepower, multi-million pound car at up to 200mph, through 5G corners and with a very real chance of having a catastrophic accident, for a 190-mile race, is almost implausible.

And then we are told an anecdote about how Hamilton once complained about his left shoe weighing more than his right. Thinking he had somehow imagined it, the team weighed his footwear and found the triple World Champion was right; the left shoe weighed three grammes more. How he sensed this with everything else going on is nothing short of staggering.

Two days later, we are watching the Belgian Grand Prix at home with a newfound admiration for what F1 drivers are capable of. Not only do they have the body of an athlete, but it is paired to the turbocharged mind of a grand master - only one playing chess at 200mph.

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.