Tomb Raider, Rhianna Pratchett and Making Characters Human

Tomb Raider launches on 5 March

Rhianna Pratchett, writer of Crystal Dynamics' Tomb Raider reboot, discusses reinventing Lara Croft and making better game characters.

As they grow older, it feels like computer games are trying to make amends. More and more, we're seeing the most egregious and criticised aspects of videogames get satirised and readapted into thoughtful creative work.

Take Journey, from thatgamecompany, which reimagined the notoriously virulent world of online gaming into something simple, picturesque and sweet. Then there was The Walking Dead, a zombie game that eschewed the typical blood, guts and chainsaws in favour of pacing, narrative and emotion.

Spec Ops: The Line was another excellent example, using old school gameplay tropes to illustrate new age thinking. Tomb Raider, by Crystal Dynamics, is doing something similar.

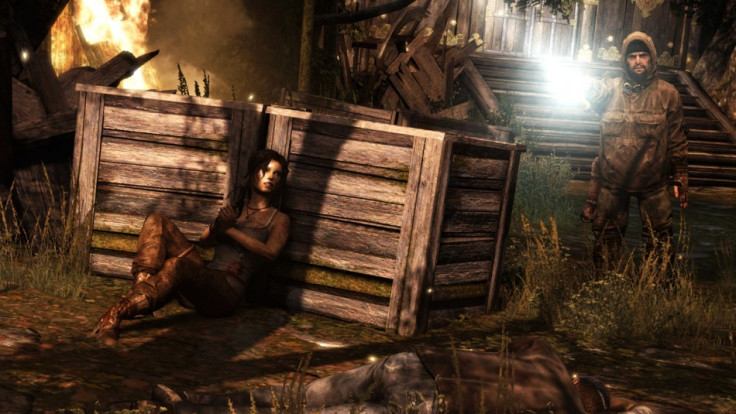

You still play as Lara Croft, but far from the chesty, winking marketing ploy of the mid-nineties, she's now a naïve, academic twenty-something, shipwrecked on a smuggler's island and seriously up against it. When she falls, she gets cut, when she slips in mud, she gets dirty. The first time Lara kills somebody, she cries. An antithesis to the Lucozade advert years, this new Lara bleeds.

"A lot of the things we associate with Lara Croft we kept in," explains writer Rhianna Pratchett. "When we think about that character, we think she's smart, she's brave, she's resourceful - all those traits are still there with our Lara, it's just that they're buried below the surface a lot more.

"She's someone that feels fear now. Old Lara was so capable that nothing would really touch her. We wanted to peel back the layers and explore her humanity, and where those traits we know come from."

Nuanced

There's a bildungsroman quality to Pratchett's Tomb Raider. Stranded on a Pacific archipelago, Lara and her expedition are being hunted by an enclave of very violent, almost savage, modern day pirates. With the group scattered and help not coming, it falls to Croft to retrieve her colleagues and make it off the island.

But she's never done this before. Well removed from the cocksure, dual-wielding tomboy of the PS1 era, Pratchett's Lara has never killed, never combat rolled and never blown anything up; she's never even raided a tomb. And rather than kick pirate ass and save the day, she'd prefer if somebody could just come and help her.

At the beginning, Lara is nervous and scared and inexperienced. There's a wonderful scene near the start of the game where she hears a distress call from one of her friends and rather than leaping up to the rescue, she begs down the radio for them to come and find her. But she's no victim. The fear and the vulnerability is there in Lara, but she's also strong and smart and adventurous. Like a good character should be, and like too few game protagonists are, Lara Croft is nuanced.

Rhianna Pratchett wanted to make her human:

"The thing with videogame characters is that they tend to be really undercooked and people don't take the time to really flesh them out. They don't treat them with the respect that a writer writing characters in any other medium would treat their character.

"Showing a videogame character terrified and scared is something that's not really done that much. She naturally turns to people she thinks are more capable than herself. But this isn't a story about a damsel in distress - she's a girl that, or rather, a human that rescues herself. It's terrifying for her but she sort of grits her teeth and does it."

In the way that the beauty of the island itself is juxtaposed with the violence and the grubbiness of the pirates, Lara's transition from student to tomb raider is mired by some truly hideous moments. The first time she shoots a person, he's practically on top of her, and we see, as Pratchett puts it "the light leave his eyes." It's an important and, in context, relieving moment for Lara but it's also bloody, and vicious.

Stronger

Later she's a stronger person, but the game reminds us that this comes at a cost. On the radio to her pal Roth, Lara says she had to kill people to get this far. "That must have been hard" says Roth. "It's scary how easy it was," she replies. It's bittersweet moments like these which are really impressive about Tomb Raider so far. We see Lara transform from a normal young person into a computer game character and it's kind of tragic. At the same time, she's able to just get on with it.

"Some of the tests Lara has to endure are physical," Pratchett says "but others are tests of how she thinks about herself. Being 21-years-old is not easy in the sense that you're still trying to get to know yourself. She struggles with things like having to take a human life, and she struggles with how unfortunately easy it was to just squeeze the trigger.

"But you can't just have a character who's terribly angsty about having to shoot people throughout the whole game, because this is a game and you have guns and you have lots of people to shoot during the game. So, we do have points where we catch up on how that's impacting her, but it's also about her coming to terms with being able to do these things.

"At the same time, we're keen to look at the other side of Lara, that geeky, almost girlish kind of excitement she has about exploring new places and finding these new archaeological things. It's not all doom and gloom. It's a real rollercoaster ride. She does some terrible things, but she unearths some amazing things along the way."

And in the sense that the natural beauty of the island combines with the brutality of the pirates, so too does Tomb Raider's story and gameplay blend to say something more about Lara.

Director Daniel Bisson has described how as Lara becomes acclimated with killing, the enemies in Tomb Raider become physically further away, as if to imply that Croft is able to put their deaths at a greater mental distance. Pratchett, whose former credits include Heavenly Sword and Mirror's Edge, says that when writing for games, you have to take design and gameplay on board:

"Writing for videogames is really unique. You learn all the rules of writing but there's a whole other set of rules for game writing, and we're changing them as we move along as well, which makes it more challenging," says Pratchett.

"In games, narrative has to be balanced with gameplay, so, you can explore the impact of violence on someone in a different way to how you would in other entertainment forms.

"Normally within a team you have people who have different views about what makes a good game. And they might be interested in their level design or their gameplay mechanics and not give a shit about your story. So, it's about finding a middle ground and showing how narratives can benefit games. Everything, animation, level design, and environmental storytelling, it all contributes to narrative.

"It's not something that should be seen as us and them. There shouldn't be gameplay here, story there. It should be harmonious. Story isn't there to harm gameplay or levels."

Literate

Exactly where the consensus has come from that story should be separate from gameplay, or that story shouldn't be a concern for games at all is hard to say. In David Kushner's Masters of Doom, John Carmack tells the rest of id Software that story in games is like story in porn; it's expected to be there but it's not important. That's an attitude mirrored throughout the sixth and a lot of the seventh console generation, though Pratchett believes it's starting to change:

"Certainly when I started out in the game industry, there were a few professional writers, but a lot of videogames writing was just done by someone else on the development team, a producer that wrote stories in his spare time or someone who just fancied a go. It was the only aspect of game development that wasn't done by a professional. That has changed, though, since I've been in the game industry.

"Still, though, there's a lot of fallout from an age when anyone could do the writing. There's a feeling that having a writer is some kind of mad luxury because anyone can write. But actually crafting a story is about more than just writing. Just being about to put letters and form words is not the same as being able to make a story that can hold up for the length of a game.

"Our audience is very literate," she continues. "The TV they watch and the movies they watch have these great characters and videogames need to compete with that."

For all their cocky heroes, chainsaw guns and laser swords, videogames seem to have a self-esteem issue. While games like Journey and Spec Ops are striving to cover up the culture's most glaring character flaws, there's a feeling among a lot of writers and players that videogames cannot be trusted with mature subject matter.

When footage appeared in early 2012 of a bound Lara Croft being groped and squeezed by a male attacker, the internet practically combusted with complaints of sexism, misogyny and porn. That scene, it was assumed, was at best propagating the weak woman archetype that permeates gaming; at worst, it was a softcore marketing tactic to make fanboys sweaty.

In reality, though, it was the knee-jerking itself that was making games look bad, not Tomb Raider. The blogs ripping on that scene were demonstrative of the same patronising tone which they were, ostensibly, rallying against; the suggestions that it might have been played for eroticism were more indicative of the sexual attitudes of gamers than anyone at Crystal Dynamics.

The groping scene was frustrating for Rhianna Pratchett, who knew what it meant in context but was unable to defend her work since she hadn't been officially announced by Tomb Raider's PR:

"It's not about the guy groping her; it's about Lara's reaction to it. It was important to make that close and personal, and count. But it became about not what people knew it was about, but about what people assumed what it was about.

"I think that scene has a power to it because of the relationship between player and player character. It's more about self-preservation than protecting Lara," says Pratchett. "We approached that scene in the way we would in any other entertainment medium. We wanted it to be honest, we didn't prolong it; it's uncomfortable because that should be uncomfortable. It's an uncomfortable and bad thing. I didn't want players feeling good about it and it's not done for titillation."

Being human

We have, recently, seen a trend of games that take old genres and do something new with them, something literate. But amends might be too strong of a word. In Journey, The Walking Dead - even in Spec Ops - there's a love for those types of videogames because that's the only way that you could so acutely bring out their strengths.

Tomb Raider has that in spades. It has a brain, but it's also an adventure game - Pratchett's writing shows that those two things needn't be mutually exclusive. Lara Croft's character is equally rounded. She's smart and she's brave, but she's also inexperienced and frightened; she's a very able killer, but she's also deeply conscientious.

But what's most important is that she's not a Female Character, at least not in the buzzword sense of the term. Emotionally insecure gaming men might prefer to conflate sensitivity, fear and vulnerability with female characters, used as they are to being the hero and rescuing the girl. But these aren't merely feminine traits, these are human emotions and as games motor towards maturity - as more professional writers appear - complexities like these will bleed into every good game character, regardless of gender.

"I don't really see Tomb Raider as a story about a female," concludes Pratchett. "It's about being human. Female characters in games have often been scantily dressed and have often been representative of a certain male fantasy. Male characters are equally ridiculous, they're kind of catering to a male fantasy as well - they've got muscles and are always powerful and so on. That means that both men and women videogame characters are both catering to a certain male fantasy on both sides. That was kind of the norm, but people have started poking fun at it, and now developers are thinking more about their characters."

Attitudes towards violence and videogame characters are changing. In twenty years or so, it's easy to imagine a lot of AAA games looking faintly risible or grotesque, like a sexist Batman strip from the forties. But, it seems, Crystal Dynamics' Tomb Raider won't be among them.

From what's been shown so far, the game has successfully reinvented one of the most indicting poster children for the industry's immaturity. No longer just a stereotype, Rhianna Pratchett's Lara Croft is a fully fledged character, and an example of how game writing could be changing.

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.