Terrifying medieval medical procedures that will make your toes curl

With no general anaesthetic nor an understanding that dirt carries disease, medical procedures and operations in medieval times would have been an excruciating and often unsuccessful experience. Here are some of the most toe-curlingly painful-sounding operations that were carried out by 'doctors' at the time.

Hot iron to treat haemorrhoids

Medieval manuscripts show that hot irons were used to treat haemorrhoids by cauterisation. This treatment was referred to by Hippocrates as early as 400BC: "Having laid him on his back, and placed a pillow below the breech, force out the anus as much as possible with the fingers, and make the irons red-hot, and burn the pile until it be dried up, and so as that no part may be left behind.

"And burn so as to leave none of the haemorrhoids unburnt, for you should burn them all up. You will recognise the haemorrhoids without difficulty, for they project on the inside of the gut like dark-colored grapes, and when the anus is forced out they spurt blood." Alternatively, sufferers could prey to St Fiacre, the patron saint of the condition. By the 12th century, Jewish doctor Moses Maimonides prescribed a much less painful method – a soak in the bath.

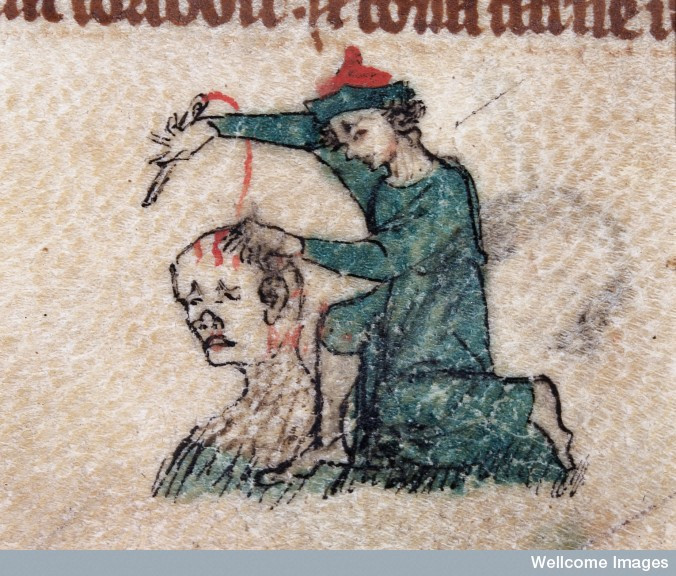

Trepanning

Drilling holes in people's skulls has been traced back thousands of years – evidence has been found going back to 6,500BC – and it was still a common procedure in the medieval period. While surgeons had the right idea about it relieving pressure on the brain (it was used to cure epilepsy, migraines and mental disorders), it was also thought the operation would expel demons from the heads of the possessed.

Evidence of the procedure being carried out in Yorkshire was discovered in 2004, with the recipient believed to have been involved in a fight. Simon Mays, a skeletal biologist at English Heritage's Centre for Archaeology, said: "It seems most probable that the operation was performed by an itinerant healer of unusual skill, whose medical acumen was handed down through oral tradition. The peasant was probably involved in the medieval equivalent of a pub fight, or could have been the victim of a robbery or a family feud."

Eye-cataract surgery

To remove a cataract, medieval physicians would insert a sharp instrument – such as a knife or a big needle – through the cornea, forcing the lens of the eye out and down to the bottom of the eye. While the operation could sometimes be successful, more often it resulted in infection or destruction of the eye. Later on, a suction technique was introduced that involved using a syringe inserted through the white part of the eye.

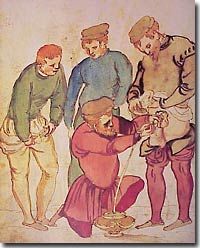

Bloodletting

Bloodletting was one of the most common medieval treatments, used for a variety of ailments. Doctors thought that excessive blood caused illness, so would remove large quantities of it via leeching or cuts. Leeches applied to the body would be left to suck blood from patients; bloodletting would mean using a knife to open a vein and allow blood to drain away. Bloodletting was so popular that doctors only started to question its use in the second half of the 1800s.

Caesarean section

Childbirth was extremely dangerous during the medieval period, and expectant mothers were told to confess their sins before labour to prepare them for potential death. Most pain relief consisted of herbal remedies and prayer. Caesareans were carried out when the mother was dying or dead – and the operation inevitably proved fatal anyway. One of the first documented successful caesareans was carried out by Jeremiah Trautman in 1610 in Wittenberg, Germany.

Metal catheters to treat blocked bladders

Blocked bladders, as a result of syphilis, kidney stones or other venereal diseases, were treated with a metal catheter. The metal tube was inserted via the urethra into the bladder. An account of it being used to treat a case of kidney stones was described in John Arderne's 14th-century Chirurgia:

"If there is a stone in the bladder make sure of it as follows: have a strong person sit on a bench, his feet on a stool; the patient sits on his lap, legs bound to his neck with a bandage, or steadied on the shoulders of the assistants. The physician stands before the patient and inserts two fingers of his right hand into the anus, pressing with his left fist over the patient's pubes. With his fingers engaging the bladder from above, let him work over all of it. If he finds a hard, firm pellet it is a stone in the bladder... If you want to extract the stone, precede it with light diet and fasting for two days beforehand.

On the third day... locate the stone, bring it to the neck of the bladder; there, at the entrance, with two fingers above the anus, incise lengthwise with an instrument and extract the stone."

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.