Umbrella Movement: Meet the Hong Kong revolutionaries who have vowed to never give up the fight

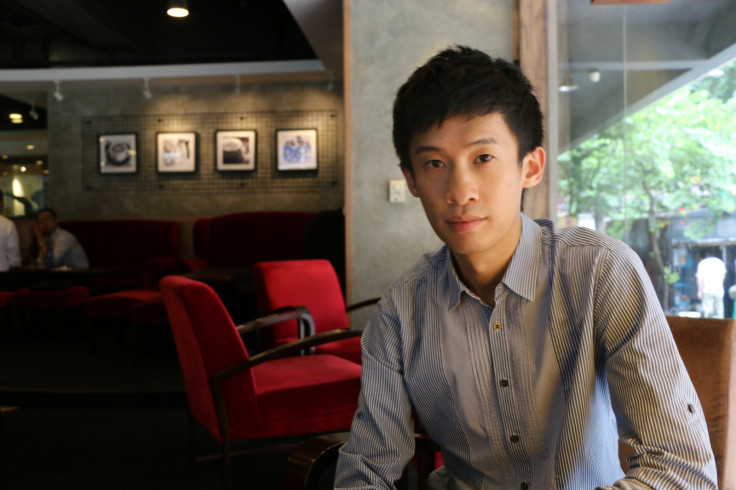

Nathan Law has just been released from Hong Kong's Police Headquarters on bail of HK$500 (£42.50). It's almost one year since he became the first arrest of the Umbrella Movement, when more than one million people peacefully occupied parts of Hong Kong, protesting against the efforts by Hong Kong's and mainland China's governments to reform Hong Kong's elections, which they claimed would erode the city's universal suffrage.

Law, along with other student activists, became the figureheads of a leaderless revolution. Now, facing a charge of inciting others to participate in unlawful assemblies, which carries a potential prison sentence, Law is defiant.

We tried our very best to fight for something we wanted – democracy, fairness and justice. But we failed. We didn't get anything after the Umbrella Movement.

"I am well prepared for any punishment and the consequences of the charges," he tells IBTimes UK. "I haven't predicted what it might be, but if it comes to prison, that will create empathy. It will show the government trying to oppress the student activists and it will reduce its legitimacy. I'm not that concerned how serious my punishment is. The legal process will show how far from Hong Kong values the law has fallen."

Earlier in the day, a small crowd had gathered outside the station to protest the decision to charge Law, along with his predecessor as Secretary General of the Hong Kong Federation of Students (HKFS) Alex Chow and Scholarism leader Joshua Wong.

Under yellow umbrellas, booming voices demanded to know why these impossibly boyish young men were being threatened with incarceration while cases of serious police brutality – one in particular, in which seven police officers were caught on camera battering an unarmed protestor – are left to fester.

Vociferous as they were, it's a far cry from the thousands-strong gatherings last September, a movement which ultimately failed in its objectives. "I don't consider it a success. It needed to achieve more. It didn't achieve the demands of the movement, but that's not to say it's a total failure. It's an experience which we can take reference from and it still has lots of impact on society," Law says.

But the legacy of those events which captured the imagination of the world is strong. While it may not bear the iconography of the yellow umbrella, it is evident when you speak to residents moved to retain what they consider to be the identity of this fiercely proud corner of the world in their own way.

In February, in his office at Hong Kong University, Professor Benny Tai – the initiator of the Occupy Central with Peace and Love – told me that the movement had outgrown mass protest, and that it had to find other means of fighting the Beijing-backed establishment. The ultimate legacy of the Occupy movement is that it has inspired exactly that.

Occupying the corridors of power

Baggio Leung is not your typical politician. At high school, he didn't know the answer to an exam question and so scribbled the surname of his favourite footballer, Roberto. His responses to WhatsApp messages are filled with emojis and until two weeks ago, the 29 year-old was working as a digital marketing manager. Now, as the founder of the Youngspiration Party, he has given it up to stand in November's District Council elections, inspired by the protests of one year ago.

"We tried our very best to fight for something we wanted – democracy, fairness and justice," he says after leaving the protest at the police station. "But we failed. We didn't get anything after the Umbrella Movement. At that time, I'm thinking: 'how can this go on?' In the past 10 or 20 years Hong Kong has been losing our beliefs and values to Beijing. What to do? My sense was to fight back somehow. The first way I could think of was the District Council."

Leung is part of an increasingly mobilised and non-mainstream pro-democracy political movement. His peers, he says, are afraid to raise children in Hong Kong. How could a boy become a good man in the Beijing-dictated national education system, or watching the propagandist news broadcasts, he asks?

The "one country, two systems" principle that allows Hong Kong to have independent civil and legal systems, including the judiciary, courts, immigration and customs and excise, from China expires in 2047. And while Youngspiration's support is drawn mainly from young people, there are older supporters who Leung says stop him on the streets of Kennedy Town eager to share history lessons of their own.

"Now in this generation, something has changed. We're asking what is next. We have some elderly supporters, 70 or 80 years old, and they say they really support us because they missed chances to defend our rights before, so today we suffer. We don't want to be the ones to regret in 30 years."

Hong Kong's awakening

The message of "localism" – of defending the values of Hong Kong – is a common one in conversations with those who were involved in the occupation.

In a busy café in Yau Ma Tei in South Kowloon, Birdy Chu stirs his milky tea between slurps of noodles, as he ponders the Umbrella Movement one year on. Chu's main regret is that he missed the clearance of the site at Mong Kok because he was sick and exhausted. For every other day, he was there with his camera, the pictures from which have ended up in an exhibition at the Goethe Gallery and a book documenting 10 years of protest in Hong Kong. A documentary is in the works.

"It inspired a lot of art, there was an explosion in creativity," the veteran activist says. "It just happened naturally. Clever little slogans can inspire more people. The yellow umbrella can become such an icon and at that moment, everyone was filled with hope. Now, I think that if this kind of huge movement can't change their [Beijing's] minds, I don't know what can."

But the creative outpouring has spread and diversified, leading to the inception of two independent news outlets since the beginning of summer.

The Hong Kong Free Press describes itself as a "new, progressive English language news source" arriving "amid rising concerns over declining press freedom in Hong Kong". Factwire, currently in the crowdfunding stage, with 139% of its target met, pits itself as a rival to some of the world's most established press.

People are tired," says Nathan Law. "They need time to rest and will eventually come out if something big happens. Something was planted in their hearts when the movement ended.

"If Paris has Agence France-Presse, New York has the Associated Press, London has Reuter, why Hong Kong should not have FactWire?" reads the blurb.

Kevin Yam, a solicitor and co-founder of the Progressive Lawyers Group (PLG), describes it as "an awakening". The genesis of his own organisation predates the Umbrella Movement by a couple of weeks, when a group of young lawyers succeeded in ousting the president of the Law Society after he voiced support for a white paper encouraging the Hong Kong judiciary to act in the national interests.

The PLG seeks, again, to defend Hong Kong values such as the rule of law and academic freedom. Since the occupation, its membership has blossomed and if the roots were independent, Yam says the Umbrella Movement acted as the steroids.

There are countless organisations such as this, representing different professions and ideologies, but united under the pro-democracy umbrella. That's not to say that all of Hong Kong is aligned as one: the pro-Beijing support has rallied too, and with their electoral turnout historically more stable there's no guarantee that anything will change post November's elections.

Hong Kong's pro-democracy movement was always a splintered thing, and while it is now less visible, there's a sense that it is simmering away below the surface, occupying more channels than ever before.

"People are tired," says Nathan Law. "They need time to rest and will eventually come out if something big happens. Something was planted in their hearts when the movement ended."

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.